For years, my wife and I have been considering offering a winter CSA, but have been hesitant. This hesitation stemmed mostly from not having any real experience growing over winter (beyond the kale and collards that persist until January in our fields), but also from lacking the proper infrastructure. This year, however, with two small tunnels up and some decent storage facilities, we decided to make the leap. But I first wanted to talk to a few winter growers to see how they run their winter CSAs to get some pointers on what to expect, what to plan for, and how to manage everything from the hoophouse to the wash/pack. Here is what I learned.

Windflower Farm

I first spoke with Ted Blomgren of Windflower Farm in Valley Falls, New York, which sits about three hours from their delivery spots in New York City. Their winter CSA is four deliveries in total, one each in the months of November, December, January, and February. It serves about 420 people––around one third of their summer share, says Ted. Though they would take more members, “that magic one-third of our membership seems to be what signs up for the winter share.”

I could focus on many elements of Ted’s CSA, but I really found their greens program compelling for its simplicity. They dedicate 8 caterpillar tunnels to greens for the winter CSA and 3 high tunnels. Four caterpillar tunnels are then harvested in November, followed by four in December. In January, they will harvest one-and-a-half high tunnels worth of greens, followed by another one-and-a-half in February. So there is only one day for harvesting in each space. They harvest everything in those sections and take their caterpillar tunnels down. In the case of the high tunnels, they move chickens into the tunnels for pest control after the greens are all cut, shutting these protected growing spaces down for the rest of the winter.

Because they are not doing a winter farmers market, this “clear cutting” helps simplify the management. The greens are grown under cover, so they see no need to wash them. They find this helps keep the greens fresh for longer anyway, and avoids the challenge of a heated wash station for winter production.

They view their winter CSA as a sort of marketing tactic. “Once a month they get a little taste of Windflower Farm,” says Ted of his customers. “For us that works because it gives us a chance once a month through the winter to remind them that we still exist, and that we’re hoping they’ll join up again in the summer.”

But the winter CSA is not, of course, just about marketing. “It might be some of the easiest money we make,” explains Ted, “because there is so much summertime inertia, so that if you’re growing ten bags of onions, it’s not that much harder to grow twelve. And that kind of goes right on down the line. Greens aren’t all that hard to pull off in the winter. Spinach is almost bulletproof. And there are some nice really cold-hardy kales and Asian greens.”

Ultimately, Ted says the winter CSA is “not something that would be among the first things we gave up. It’s a nice profit center.”

Wolf Pine Farm

The second farmer I spoke with was Tom Harms of Wolf Pine Farm in Alfred, Maine. For the last nine winters Tom and has wife have been running a winter CSA with about 55% of their CSA going to nearby cities like Portland and Lewiston on a truck, and the remaining being picked up on their farm. Starting the second week of October and going until the second week of March, there are seven shares in total going to about 400 members.

One of the things I found interesting about their approach was how much of their winter shares are aggregated from other local farms. In fact, in the early years, says Tom, “very little of the food in the shares came from our farm.” This is different from their summer shares, which they produce entirely themselves. Over time they have slowly adjusted their crop plan to produce more of the share from their own farm––greens, alliums, and root crops for instance––but they still like to rely on some other farms for items they don’t grow themselves such as apples, grains, and dry beans. “For us,” he says, “that model has worked well, because in Maine in the wintertime it feels harder for us to do all of the things that we would want to do to create a diverse box of vegetables for winter eating.”

By aggregating some of the share, Wolf Pine doesn’t have to keep orchards and the specialized storage facilities for items like apples. Instead, those items can be delivered to the farm right before the share is packed into boxes.

To manage this aggregation, Wolf Pine does not partner with these farms. “It is not a multi-farm business model,” says Tom. They are buying in bulk and filling the boxes at the farm, then distributing the shares themselves. “All the other farms we work with, we’re buying product from them as if we were a grocery store and then we just compile it into the shares.”

What I appreciate about this model is that it accomplishes the goal––as Ted pointed out above––of keeping your customers thinking positively about your CSA while earning a little wintertime income. It lowers their stress by not having to produce everything themselves. Plus this model brings the local farming community into it, adding a little more income to those fellow farmers’ winter wallets as well.

Rocky Glade Farm

Lastly, I spoke with Julie Vaughn of Rocky Glade Farm outside of Franklin, Tennessee, near Nashville. My wife and I visited the Vaughns a couple years back and were really taken with their operation, their family, all of it. Though they sell some to chefs and restaurants through the summer, they are primarily a winter farm. Their CSA runs from the first week of October until the beginning of May. It is delivered every other week with a new-this-year “fall share” option that goes just until Christmas. After strawberry season, they do not do a summer CSA or market at all.

In our conversation, I took a lot away from hearing Julie describe how they manage their hoop houses, of which they have three, all 35’x144’. These tunnels are currently all double poly, non-heated, but Julie says they are thinking about moving away from double poly as they feel its cutting down too much on light, and they haven’t seen enough of a temperature bump to justify it. Instead, they are thinking they will return to single poly covering and continue relying on row cover for cold protection.

In terms of growing, they try to think of these tunnels as storage units. Julie says they load them up with vegetables and pick out of the fields as long as possible, relying on the tunnels only when it becomes necessary.

“I like to have them completely full by the first of November,” says Julie. By that date, she tells me, it’s important to have her plants already established to get them through until the days get longer.

Rocky Glade also doesn’t rely much on the beds against the tunnel sidewalls for winter growing. These beds are used for quick crops like radishes, and for very hardy crops like green onions and green garlic. Beyond that, Rocky Glade likes to have the wall beds completely harvested by the time the winter sets in.

As for the “fall share,” this is the first year they’ve tried it and Julie tells me they are already seeing a lot of new interest from having this option available. How it works is that customers can sign up to go all the way through the winter (a “full share”), or test the CSA by just doing the “fall share,” with the last delivery coming right before Christmas. This “fall share” has brought in new customers who want to test the waters and who will, of course, have the option of sticking around after the Christmas share.

In fact, they’ve always emphasized making the Christmas delivery unique, which may help with that retention. This is another element I really appreciate how they approach their winter CSA. “We always try to make it special,” says Julie.

They keep bees, for example, so they will often give a one-pound jar of honey to their shareholders in the Christmas box. They have also purchased items from craft vendors at the market at a discounted price to distribute in the share, allowing the vendor to put information in with it as an advertisement. The vendor gets the benefit of free advertising to people who regularly visit the market and their craft gets to act as a Christmas gift for Rocky Glade CSA members. Then in May, Rocky Glade always tries to end their CSA season by giving a quart or two of berries. Last year, she tells me the spring came so early they gave four quarts of strawberries––quite a parting.

Indeed, ending each of their shares this way––with goods that people love––helps to send them off “with something to remember you by.”

It’s a good way to keep customers coming back. Julie laughs, “makes them forget about all the Swiss chard they had to eat in January.”

Our approach

Being our first full winter season, my wife and I have decided to keep our winter CSA relatively small––around twenty members running fifteen deliveries in total from early October until February. We are located in central Kentucky, so winter growing is not the challenge it is for Ted and Tom but we certainly get our share of cold and dreary here in 6b. In preparation, we grew Gold Nugget sweet potatoes, Laurentian rutabagas, Cupar storage carrots (and several other varieties for fresh), potatoes, as well as winter squashes including the variety Honeynut popularized by chef Dan Barber which is incredibly tasty. We also produced some baby ginger and turmeric. Our fields are loaded with Brussels sprouts, collards, pac choi, Hon Tsai Tai (a favorite flowering broccoli of ours), some cold hardy broccolis, carrots, spinach, radicchio, and lettuce, among many other things.

We’ve got two tunnels, both 15X52 that are now fully planted at the date of this writing (September 12th). I’ve placed hardier crops on the wall beds including Nash’s Green and Olympic Red kale, plus some Corvair Spinach. One wall bed has Swiss chard interplanted with some green onions for the colder months. Our tunnels are single poly, so we are going to supplement with Agribon AG-30 row cover for cold protection. My goal is to not harvest much if anything from these tunnels until January. We’ll see what the winter hands us.

Overall, I’ve taken a lot of insight from these conversations, and in some surprising ways. From Ted, I’ve started to think of our winter CSA more like a marketing tactic––a way to keep people engaged with your farm and thinking about you through the winter. To that point, I’ve also started looking for some local organic fruit producers with the possibility of offering apples or pears with our share, as both Tom and Ted do. I really like the Christmas basket idea from Julie. We had already planned on a nice Thanksgiving basket with Brussels sprouts, butternut squash, and sweet potatoes but now we’re scheming on what we can offer in the Christmas basket that might keep people excited for spring…and possibly next year’s winter CSA.

Jesse Frost is a vegetable grower and freelance journalist in central Kentucky. He has written for The Atlantic, Civil Eats, Modern Farmer, Hobby Farms and others.

It’s not too late for online/preorder seedling sales, farmers market custom bags, and We Give a Share

It’s not too late for online/preorder seedling sales, farmers market custom bags, and We Give a Share

Farmer to Farmer Profile

Farmer to Farmer Profile

Why is the flower micro-farm best suited to a laser focus on one or two enterprises versus a balance of several? It is because of the long maturity of flower crops and the specific and conflicting demands of different types of flower enterprises. For example, some of the most common ways for farms to sell their flowers are at a farmers market, wholesale, from a flower stand/truck, a CSA, and weddings/events. These outlets can be compared on their need for similar types and quantities of flowers.

Why is the flower micro-farm best suited to a laser focus on one or two enterprises versus a balance of several? It is because of the long maturity of flower crops and the specific and conflicting demands of different types of flower enterprises. For example, some of the most common ways for farms to sell their flowers are at a farmers market, wholesale, from a flower stand/truck, a CSA, and weddings/events. These outlets can be compared on their need for similar types and quantities of flowers.

For most established growers, the easiest place to start selling flowers will be mixed bouquets and single stem/small bunch retail sales. These are the flowers you can sell to your existing customers and they are easy to incorporate into farmers market, CSA, and grocery sales. But there are lots of other outlets out there, including florists, weddings and events, business subscriptions, value added products, and wholesalers.

For most established growers, the easiest place to start selling flowers will be mixed bouquets and single stem/small bunch retail sales. These are the flowers you can sell to your existing customers and they are easy to incorporate into farmers market, CSA, and grocery sales. But there are lots of other outlets out there, including florists, weddings and events, business subscriptions, value added products, and wholesalers.

I made a trek out to Wisconsin in June. I’ve been lucky enough to visit this gorgeous state a few times, and I was glad to return. Wisconsin is the state with the second most organic acres in the country, behind California. It’s been an important crucible for the organic ag movement since the beginning. Out of the 177 of Chris Blanchard’s Farmer to Farmer podcasts, 21 featured Wisconsin-based businesses. From that list I chose two farms to visit and interview for this column.

I made a trek out to Wisconsin in June. I’ve been lucky enough to visit this gorgeous state a few times, and I was glad to return. Wisconsin is the state with the second most organic acres in the country, behind California. It’s been an important crucible for the organic ag movement since the beginning. Out of the 177 of Chris Blanchard’s Farmer to Farmer podcasts, 21 featured Wisconsin-based businesses. From that list I chose two farms to visit and interview for this column.

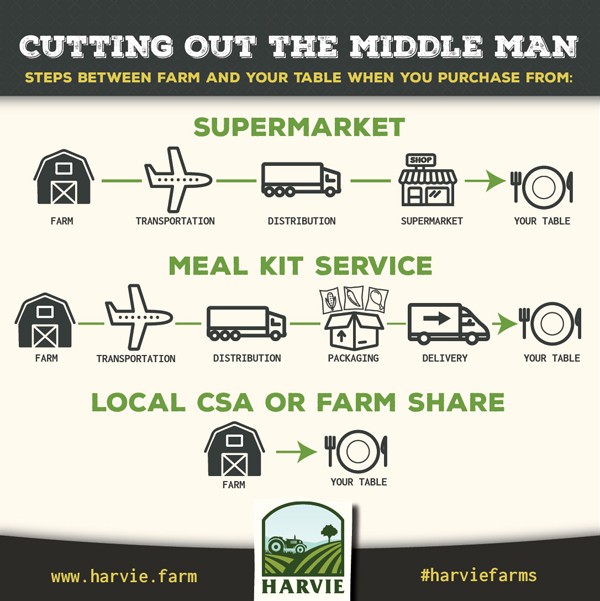

“CSA is dead” is a refrain I have heard from multiple farms in the past few years. I started to hear rumblings of a problem with the CSA model in 2014 through the CSA Farmer Discussion group that I manage on Facebook which brings together over 2,500 CSA farmers from all over the world. Farmers reported that they were having trouble attracting and retaining membership.

“CSA is dead” is a refrain I have heard from multiple farms in the past few years. I started to hear rumblings of a problem with the CSA model in 2014 through the CSA Farmer Discussion group that I manage on Facebook which brings together over 2,500 CSA farmers from all over the world. Farmers reported that they were having trouble attracting and retaining membership..jpg)

It’s an incredibly cool, clear and dry July day in Massachusetts as I make my way to Brookfield Farm. Dan has arranged for me to visit at 2PM on a Thursday so I can see this bustling CSA farm at distribution time. I arrive just before the appointed hour, and see the last details of the setup being handled by apprentice Ellen. Dan and Karen are bustling around the corner, checking that the room is ready for the deluge of customers to come.

It’s an incredibly cool, clear and dry July day in Massachusetts as I make my way to Brookfield Farm. Dan has arranged for me to visit at 2PM on a Thursday so I can see this bustling CSA farm at distribution time. I arrive just before the appointed hour, and see the last details of the setup being handled by apprentice Ellen. Dan and Karen are bustling around the corner, checking that the room is ready for the deluge of customers to come.

Getting to High Ground Organics means going through the belly of the beast of California’s agricultural sweet spot – the Central Coast. This is where high value crops are grown right to the property line, right next to towns and suburbs, cheek by jowl. The proximity to the Pacific Ocean mitigates the climate of this region so it’s never that hot and never that cold; they can grow and harvest strawberries from March to October.

Getting to High Ground Organics means going through the belly of the beast of California’s agricultural sweet spot – the Central Coast. This is where high value crops are grown right to the property line, right next to towns and suburbs, cheek by jowl. The proximity to the Pacific Ocean mitigates the climate of this region so it’s never that hot and never that cold; they can grow and harvest strawberries from March to October.

Fifth Crow Farm lies nestled below some ragged hills – the native grass fully brown, the oaks wide and green. The farm grows 50 acres of certified organic crops on 150 acres of leased land, including vegetables, cut flowers, dry beans and eggs. The farm land is completely flat, tucked in a tiny valley in zone 9B. Believe it or not, just across the street, a mere two miles from the ocean, there are acres and acres of open land with cows grazing. How can land so close to such beauty, and with such a wonderful growing season be devoid of development? The answer is complicated, but mostly it’s because the parcels of land have always been quite large, and much of it is being purchased for conservation purposes.

Fifth Crow Farm lies nestled below some ragged hills – the native grass fully brown, the oaks wide and green. The farm grows 50 acres of certified organic crops on 150 acres of leased land, including vegetables, cut flowers, dry beans and eggs. The farm land is completely flat, tucked in a tiny valley in zone 9B. Believe it or not, just across the street, a mere two miles from the ocean, there are acres and acres of open land with cows grazing. How can land so close to such beauty, and with such a wonderful growing season be devoid of development? The answer is complicated, but mostly it’s because the parcels of land have always been quite large, and much of it is being purchased for conservation purposes.

Jack and Beckie Gurley’s Calvert’s Gift Farm was among the first certified organic farms in Maryland. Over the years, the couple has mentored many new farmers, and in April 2015, they took it a step further and created the Chesapeake Farm to Table (CFT) food hub to generate and coordinate reliable sales to help small farms operate profitably. Twice a week, CFT combines freshly harvested farm products from 25 farms and a ramp forager in West Virginia for delivery to Baltimore, Annapolis and Washington, D.C., area restaurants.

Jack and Beckie Gurley’s Calvert’s Gift Farm was among the first certified organic farms in Maryland. Over the years, the couple has mentored many new farmers, and in April 2015, they took it a step further and created the Chesapeake Farm to Table (CFT) food hub to generate and coordinate reliable sales to help small farms operate profitably. Twice a week, CFT combines freshly harvested farm products from 25 farms and a ramp forager in West Virginia for delivery to Baltimore, Annapolis and Washington, D.C., area restaurants.