By Rowan Steele

What does it take to launch a new farm business? Perhaps more importantly, what can communities do to ensure opportunities exist for the next generation of farmers? These are questions many of us in the farm world have been grappling with as the implications of too few farmers would have profoundly negative impacts to our food system, economy, natural resources, cities, and countryside. While there are significant efforts underway across the country to support the development of new growers, this article depicts the multi-organization farmer development efforts in Northwest Oregon.

Farmers in Oregon are on average 60 years old, a couple of years beyond the national average. In addition to an overall drop in farmers, we’ve witnessed declining numbers of farmers under the age of 44 and beginning farmers (defined as someone owning a farm business for less than ten years). As the current generation of farmers grows older, it is anticipated that 64% of Oregon’s farmland will change hands over the next 20 years.

That’s a scary figure, as it’s commonly accepted that without a healthy new generation of skilled and knowledgeable producers, there will be greater amounts of farmland lost to non-farm uses, less food, fuel and fiber being produced in our communities, and less active resource management. In addition, without robust farm activity and healthy farm communities, we lose opportunities to maximize the benefits associated with good land stewardship, such as carbon banking, riparian habitat restoration, and groundwater recharge.

The good news is there is a growing wave of younger farmers interested in making agriculture their career path. Many of these individuals come from non-farm backgrounds yet see agriculture as a rewarding occupation that aligns with their values and serves the greater good. However, incredible barriers exist for even the most competent new farmers. These challenges can be boiled down to four main categories:

Access to capital

Access to farm training

Access to markets

Access to farm networks

Access to capital is synonymous to one’s ability to secure farmland, equipment, and infrastructure. Most lenders won’t work with agricultural businesses, especially those outside the industrial or commodity model. While small farms aren’t beholden to the same capital investments as large operations, even the smallest of operations have capital needs that exceed their financial capacity. For many growers, securing farmland via long-term lease is an ideal low-cost alternative to purchasing, but this does not address the financial needs associated with scaling up, or with increasing efficiency if one is unable to make capital investments.

Access to farm training has become much more prevalent over the last 10 years and can be acquired through programs offered by nonprofits or educational institutions. While not all communities have such organizations, there is no better learning experience than simply working for a commercial farm operation.

Established farm businesses of any size can have issues finding markets. What makes it different for a beginning small farm is that direct outlets in many areas are becoming saturated, and it can be challenging to provide the consistency needed to secure or maintain accounts. Several farmers markets in the Portland area have reserved booth space for beginning farmers seeking to get a foothold in competitive markets. One example worth highlighting is the Woodlawn Farmers Market’s Introducing Farmers Program, which offers new growers reduced booth fees and provides basic marketing resources (such as a canopy, weights, tables, baskets, and scale) as well as a market sales training. Upon their first visit, program participants are paid to present their farm and operation to customers.

Access to farm networks is perhaps the least considered barrier to new farmers but may be the biggest gauge of success. Since the majority of new farmers in Northwest Oregon are not coming from farming backgrounds, and because many farm communities have been fractured over the last few decades, it can be extremely challenging to navigate the complexities of running a farm business. Where can you source specialized equipment? Who do you call when something breaks? What is the best approach for managing a specific pest? The answers to these types of questions become much clearer when farm communities and networks are intact.

On top of these “traditional” barriers to beginning farmers there are a host of other challenges to immigrant and refugee growers. These can include financial and computer literacy limitations, a poor grasp of American consumer habits, language barriers, and many other aspects that most of us regularly take for granted. A robust, vibrant, inclusive, and equitable food system is one that offers opportunities for everyone. In an effort to address lowering the traditional barriers listed above it is critical that we don’t lose sight of the needs of our least privileged producers.

Oregon’s approach

New farmers come from a host of backgrounds and have different skills, levels of experience, and varying gaps in their knowledge. Due to this, the farm development model being employed in Northwest Oregon is multi-organizational, with different groups playing specific roles. These organizations act independently but have also been actively working to galvanize and streamline services. The ultimate goal is that anyone with interest in farming can locate an appropriate entry point and receive support along their path from farm intrigue to retirement and succession.

The following is a highlight of the key stages and groups who are facilitating Northwest Oregon’s farmer development pathway.

Entry level programs

The majority of interest in farming comes from individuals with virtually no production experience. While most of these folks won’t become farm business owners, their participation in food production is critical for many reasons.

For example, they provide farm labor in an era where finding workers is becoming increasingly challenging, or their time farming may offer a greater appreciation for agriculture and lead them to make better choices with their food dollars. In addition, some of these individuals with farm intrigue will burn out, come to terms with the narrow margins, and then continue to show interest in a farming career. These are the most promising future farmers who warrant investment and support.

Some of the primary entities involved in entry-level farmer development in Northwest Oregon include:

Rogue Farm Corps – A nonprofit that partners with local farmers to provide full season on-farm internships and advanced apprenticeships, which include classes and farm tours.

MudBone Grown – A for-profit business partnering with the Oregon Food Bank that offers paid apprenticeships for farmers of color. For ten spaces this year they received over 90 applications.

Bridge City Farm School – A for-profit operation that caters to new growers whose life circumstances don’t allow for on-farm living.

Zenger Farm – A nonprofit that provides comprehensive urban agriculture and food system education. They typically field over 60 applications for four paid first-year farming apprentices. 80% of their graduates stay in farming.

While all of these programs are unique, each one delivers a broad, hands-on farming experience to their participants. It’s rare that individuals leaving these programs are ready to launch a farm business, but they are typically prepared to take on management roles on existing farms, something that is sorely lacking in this region. In many circumstances those with farm ownership aspirations will go to work on a small farm following their program experience.

Farm incubation

One farmer development tool that has gained traction in the last few years is farm incubators. These land-based, multi-grower projects provide training and technical assistance to beginning farmers. Of the roughly 130 incubator programs across the United States, each one is distinctive in its scope, scale, and emphasis.

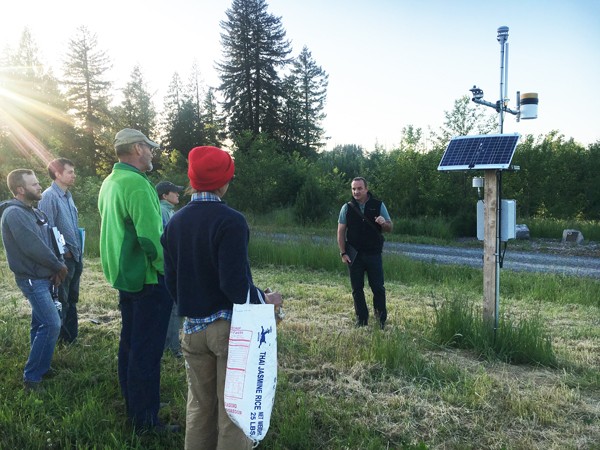

The Headwaters Incubator Program (HIP) is run by the East Multnomah Soil and Water Conservation District (EMSWCD). It seeks to support experienced growers who lack a direct path to farm business ownership and help them surmount the traditional barriers to beginning farmers. The ideal candidate has at least three years of production experience with one or more full seasons managing crews or farm systems (cultivation, irrigation, propagation, etc.). To this end, HIP participants lease farmland, equipment, and farm infrastructure at the 60-acre Headwaters Farm for up to five years. After the farmers graduate, EMSWCD seeks to support them in their transition onto their own land that is secured through purchase or a long-term lease.

In addition to affordable access to farm resources, program participants receive training and support in conservation agriculture as well as farm business planning and development. Farmers also coordinate on bulk purchases for amendment, drip irrigation supplies, agricultural plastics, and seed. More importantly, program participants have a built-in network of fellow beginning farmers who help troubleshoot, share ideas, lend resources, or simply commiserate.

There are currently 14 farm businesses participating in HIP, consisting of 20 farmers in all. Most of these operations are diversified mixed-vegetables; however, there are also cut flowers, medicinal herbs, and livestock operations. Each season, as a handful of participants graduate, a new cohort of growers is brought in to fill that void.

Small farm community

Northwest Oregon boasts a healthy small farm community that is cooperative and close. These established farm businesses rely on a network of services that include: Oregon State University’s Center for Small Farms and Community Food Systems, Extension Services Small Farms Program, Soil and Water Conservation Districts, Friends of Family Farmers, and the Portland Area CSA Coalition, among others.

Small farms play a critical role in supporting the next generation of growers, both by fostering learning opportunities for paid labor and as a tour or host site for individuals in entry-level training programs. What makes this relationship so powerful is that as new farms become established, they hire and take on apprentices themselves, thus becoming the mechanism for uplifting the next round of motivated beginning growers. In essence, this model is generating new farmers to generate new farmers.

Conservation

Despite many of the necessary pieces in place to continuously develop new farmers, securing suitable production ground remains a major limiting factor. Even with Oregon’s strong land use regulations that prioritize farmland protection and limit sprawl, external pressures, strong interest from rural estate buyers, and large parcel sizes keep land prices inaccessible for most new growers. This hurdle requires additional interventions for the farmer development model to be successful.

A particularly promising avenue for affordable farmland access in Northwest Oregon comes from conservation organizations, such as non-profit land trusts and soil and water conservation districts. These organizations use techniques to help address farmland affordability and access, including the purchase of working farmland easements, which requires the property remain in productive agriculture in perpetuity and may also prohibit specific poor stewardship practices.

The limitations on future use make the site less attractive to industrial production and hobby farmers, which can help ensure future land affordability. Another strategy is “buy-protect-sell.” In this instance the conservation organization acquires farmland—often at threat of conversion to other uses—and then sells the property with a working farmland easement, sometimes after making investments to restore the onsite natural resources or farm facilities.

With no other agriculturally focused land conservation organizations operating in Northwest Oregon, EMSWCD launched the Land Legacy Program to, among other things, help ensure the sustainability of local agriculture while also protecting and enhancing on-farm resources. To date, EMSWCD has acquired several farm properties, with one expected to be resold with a working farmland easement. While EMSWCD’s Land Legacy Program does not focus solely on the needs of new farmers, it is an important component of the undertaking.

Moving forward, as EMSWCD acquires additional farm properties, there may be opportunities to make this farmland available for HIP graduates and other new or disadvantaged farmers. Given that large farm parcels are most cost-effective per-acre and therefore more likely to be what the Land Legacy Program secures, any property beyond the scope of a single operator could be farmed cooperatively by multiple growers. This scenario is especially well suited to HIP graduates, who are accustomed to sharing resources and managing independent farm businesses on a multi-farmer site.

What’s next?

In addition to refining the farm development network, one area that shows great promise is providing incubator farm graduates with farmer development packages and continuing professional development as they transition onto a new piece of ground. This could include legal support, financing, bookkeeping, and sales and marketing training, among other essential services.

Ecotrust, a nonprofit based in the Pacific Northwest with a mission of creating economic opportunity, social equity, and environmental well-being, recently launched an Agriculture of the Middle Accelerator Program focused on providing these types of services to small and mid-sized farm businesses that are scaling up. The Accelerator is offered in a cohort model, with some individual support provided to each participating business. While this program is unique in the wraparound services provided, producers not in Ecotrust’s service area might seek out similar resources from local Small Business Development Centers or Extension offices.

Another exciting recent development is the merging of private capital and values investors seeking to fund small farms engaged in sustainable agriculture. One such example of mission driven capital in Northwest Oregon is New Island Capital, which offers favorable financing packages to beginning farmers seeking to purchase and improve farmland.

Conclusion

There is no single organization capable of providing all of the support services necessary to deliver continuous opportunities for beginning farmers. The need is simply too great and the challenges facing new growers too dynamic. Instead, a slew of groups with specialized niches working in concert is ultimately what’s needed to facilitate the paradigm shift.

While no community has identified the perfect farmer development program, the innovative and abundant approaches being employed in Northwest Oregon offer an example of a galvanizing network committed to ensuring a robust next generation of growers. And while the jury is still out on the overall viability of this model, the interest being generated from potential future farmers, farm advocates, established growers, consumers, and lawmakers is extremely encouraging and has immense value in itself.

Rowan Steele Manages the Headwaters Incubator Program for the East Multnomah Soil and Water Conservation District in the greater Portland, Oregon region. He works to develop new farm businesses, promote good stewardship, and demonstrate the nexus between natural resources conservation and farm viability. For more information, visit emswcd.org/farm-incubator.