By Franklin Egan, PASA

This is the second article in a series on soil health challenges and innovations revealed through case studies that are part of the Pennsylvania Association for Sustainable Agriculture’s ongoing Soil Health Benchmark Study, a citizen-science project begun in Pennsylvania in 2016. Read the first installment on the GFM or PASA website.

In 2013, Cameron and Audrey Pedersen relocated Bending Bridge Farm to twelve acres of land they purchased near Chambersburg, PA. Given their new land had been in continuous conventional corn production for decades, the soil was in dire shape. The first spring working that ground they could not even get a chisel plow to break the surface because the soil was so compacted and crusted.

Cameron and Audrey knew they needed to develop and implement a comprehensive plan to regenerate the health of their soil, and they wanted this plan to adhere to organic methods. As part of their strategy, they have been practicing a diverse crop rotation that includes long windows for over-winter and summer cover crops. Because of this, Cameron and Audrey keep their land in living cover for 248 days of the year—making Bending Bridge a leader in cover cropping among the other 23 vegetable farms participating in PASA’s Soil Health Benchmark Study.

However, while their regenerative soil health plan was noticeably improving water filtration and friability, it was not achieving all of its intended results. After four years of diligent cover cropping, Bending Bridge Farm’s levels of organic matter barely budged. In fact, in some areas organic matter levels appeared to be backsliding—according to their Cornell soil health test results, the same field that had 2.8 percent organic matter in 2013 had dropped to 2.3 percent in 2017.

Interestingly, Bending Bridge’s levels of active carbon—the portion of organic matter that can serve as a readily available food source for microbes, and a leading indicator of total organic matter—have increased about 300 percent since 2013. A soil’s level of active carbon can respond to changes in soil health management years earlier than its percentage of organic matter, so for Cameron and Audrey this is a positive sign. Still, change is coming rather slowly.

A field day yields soil health insights

To help dissect and improve their soil health management strategy, Cameron hosted a field day with a group of his peers at Bending Bridge this past March. Attendees included other participants in our Soil Health Benchmark Study, several local farmers, and staff from the Cornell Soil Health Lab and PASA.

We learned that Cameron’s go-to fall cover crop is a rye/vetch mix, but he finds terminating this hardy cover organically the following spring to be a big challenge, often requiring passes with a chisel plow, disc plow, and rototiller over a three-week period. He is concerned that whatever progress he is making on organic matter and aggregate stability with cover cropping, he is knocking back each season with this bout of intense tillage. While other vegetable farmers in our study who adhere to organic practices have been able to find balance between growing or maintaining organic matter levels and intensive tillage, it may be that special techniques are required when you’re starting with an extremely degraded soil.

We discussed tactics Cameron and Audrey could try for reducing the soil disturbance involved in terminating their spring cover crops. Bob Shindlebeck from Cornell proposed using a roller crimper to terminate the rye/vetch mixtures. A roller crimper is a drum or cylinder with curved blades mounted to a tractor. As the roller crimper passes over a cover crop, it crushes the plant stems and lays them down in a thick mat. The mat provides a weed-suppressing mulch into which farmers can plant vegetable transplants or large seeded crops without tilling.

While roller crimpers are increasingly popular on row crop farms, there’s been less research on and application of the implement for organic vegetables, although Rodale Institute and Dickinson College Farm are currently conducting some experiments. Considering the limited information available, Cameron was understandably skeptical about some of the practical details involved with this equipment. For instance, how would starter fertilizer be applied underneath the cover crop mulch, and how would successions of tomato plantings be managed as the mulch decays?

Several farmers in the group wondered if it might be better to replace the multiple chisel, disc, and rototiller passes with a single, aggressive pass of a moldboard plow. Although the moldboard plow is infamous for its soil-destroying capabilities, a once-and-done pass with a moldboard could perhaps be less disruptive than a drawn-out month of less intensive tillage. This is a controversial idea from the perspective of available research, but the farmers in our group thought it deserves further investigation in organic vegetable systems given their experiences and observations.

Reducing tillage

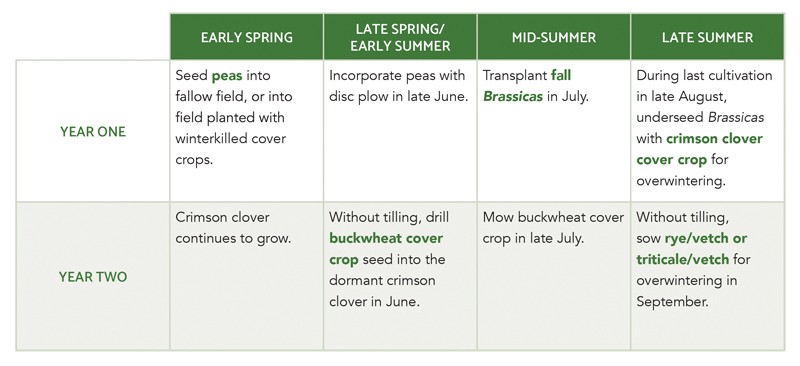

Due to its impressive biomass production, terminating rye is a common challenge on organic vegetable farms. Considering this, Cameron and field day attendee Jennifer Glenister of New Morning Farm in Hustontown, PA arrived at a creative solution to this problem: rotating cash crops to a full-year cover crop—such as a legume, like crimson clover.

Jennifer explained how this approach might look on her farm (see table above). In year one, she would plant early spring peas into a bare fallow field, or a field that had been planted to a winter-killed cover crop the previous year (like radishes). The peas would be incorporated with a disc plow in late June, then fall brassicas would be transplanted in July, with crimson clover under-seeded at the last cultivation in late August. The clover would grow until the following season, when it would set seed and go dormant.

This is one of the advantages of working with a biennial like crimson clover: its life cycle winds down on its own in the second year, so less tillage may be needed to terminate it. Jennifer would then no-till drill buckwheat into the clover in June, mow the buckwheat down in late July, and follow up with a no-till planting of rye/vetch or triticale/vetch in September. By keeping rye in the rotation, Jennifer maintains its benefits in terms of biomass, weed-suppression, and winter hardiness.

In contrast, the rotation currently implemented on New Morning Farm involves early spring peas, followed by buckwheat in the summer, followed by a triticale/vetch planting in the fall. The next July, the triticale/vetch is terminated with multiple passes of a disc plow before the field is transplanted to fall brassicas. Transitioning to a rotation that includes a full-year cover crop will allow Jennifer to produce the same number of cash crops/acre over any two year period, while cutting tillage in half and building soil health for an entire year.

Thinking along the same lines, Cameron from Bending Bridge is applying a similar strategy this season. He will be relying less on rye/vetch covers, and more on crimson clover. Cameron feels he and Audrey can commit one and a half acres of their 12-acre operation to a full-year cover crop and still meet their production goals. In fields where they plan to use rye/vetch covers, they will avoid the intense bout of spring tillage by using these fields for fall brassicas only. That way, they can terminate the rye in the spring with less tillage, and give the residue plenty of time to break down over the first half of the season before transplanting the fall brassicas.

As we continue to monitor Bending Bridge’s soil health, we’re looking forward to seeing if Cameron and Audrey are able to get out of their organic matter rut and take their soil health to the next level by incorporating full-year cover crops into their crop rotation and reducing tillage.

Find more information about PASA’s Soil Health Benchmark study—including how to participate—on their website at pasafarming.org.

Franklin Egan leads the PASA education and research programs. He holds a PhD in ecology from Penn State University, and he has led research on topics including biodiversity conservation on farmland, environmental risks from genetically-modified crops, and soil health. Franklin has also worked as a research ecologist for the USDA Agricultural Research Service, and on vegetable and dairy farms in New York and Wisconsin.

When we started farming in 1983, there were few models of organic, horse-powered market gardening. So we used the traditional practices for growing field crops here in north-central Pennsylvania, preparing a seedbed with the moldboard plow, spring tooth harrow and cultipacker. We quickly realized we needed to put a whoa on moldboard plowing to dependably establish dryland produce.

When we started farming in 1983, there were few models of organic, horse-powered market gardening. So we used the traditional practices for growing field crops here in north-central Pennsylvania, preparing a seedbed with the moldboard plow, spring tooth harrow and cultipacker. We quickly realized we needed to put a whoa on moldboard plowing to dependably establish dryland produce.

It only took me a few minutes to decide to put the Beech Grove Farm Fall Tour on my schedule upon seeing the advertisement in a Pennsylvannia Association for Sustainable Agriculture (PASA) e-blast. Visiting this horse-powered vegetable operation has been on my farm “bucket list” for many years. I hold Anne and Eric Nordell as some of my most highly respected farm heroes.

It only took me a few minutes to decide to put the Beech Grove Farm Fall Tour on my schedule upon seeing the advertisement in a Pennsylvannia Association for Sustainable Agriculture (PASA) e-blast. Visiting this horse-powered vegetable operation has been on my farm “bucket list” for many years. I hold Anne and Eric Nordell as some of my most highly respected farm heroes.

If you’ve been a subscriber to Growing For Market (or even if you haven’t), you’re probably familiar with the many advantages of no-till agriculture. No-till methods can reduce a farm’s carbon footprint, promote complex soil biology, and preserve and build organic matter.

If you’ve been a subscriber to Growing For Market (or even if you haven’t), you’re probably familiar with the many advantages of no-till agriculture. No-till methods can reduce a farm’s carbon footprint, promote complex soil biology, and preserve and build organic matter.

I met Jacob Bach through the Michigan State Extension on a visit to his farm with my professor. Over the two years since that first visit, I have come to see a kind of courage in the way he approaches farming; whole-heartedly trying machines and methods and moving in even opposite directions over the years as he develops his own style of growing. I have learned a great deal from the nuts and bolts of his techniques and been inspired by the breadth and depth of his approaches.

I met Jacob Bach through the Michigan State Extension on a visit to his farm with my professor. Over the two years since that first visit, I have come to see a kind of courage in the way he approaches farming; whole-heartedly trying machines and methods and moving in even opposite directions over the years as he develops his own style of growing. I have learned a great deal from the nuts and bolts of his techniques and been inspired by the breadth and depth of his approaches.