I wrote about the mysteries and complexities of soil microbiology and why it’s vital to care for the incalculable number of microbes below our feet in “Soil: A living, breathing ecosystem” in the January 2022 GFM. An entire ecosystem exists within the soil and is in constant flux — eating, breathing, communicating, and adapting to environmental stresses. If conditions are less than ideal, the symbiotic relationship between plants and microorganisms is compromised.

Two Farmers and a t-post: 100 feet can be crimped in about 10 minutes, resulting in a terminated cover crop without tillage. All images courtesy of the author.

Two Farmers and a t-post: 100 feet can be crimped in about 10 minutes, resulting in a terminated cover crop without tillage. All images courtesy of the author.

The goal of this second article is to provide growers with a few tools to help bolster their soil’s biology so plants (and soil) can live at their fullest potential. Since every farmer has a unique set of circumstances (including scale, crop selection, climate, season, and soil type), there is no single solution. Thankfully though, with the help of the following principles, you can find a combination of soil management practices that will work best for your farm:

Minimize soil disturbance: Aggressive disturbance is devastating to the soil’s microorganisms that call the soil their home.

Maximize photosynthesis: Plants take a percentage of the energy they convert from sunlight and CO2 and send it down into their roots in the form of soluble carbon exudates, which attract and feed microbial populations in the rhizosphere.

Grow a diversity of crops: A diversity in plants equals a diversity in microbial species.

Keep the soil covered: Mulch, tarps, and plants help protect the soil surface.

Avoid: herbicides, pesticides, fungicides, and chemical fertilizers.

Following these guidelines in your day-to-day farming practices will undoubtedly support and encourage healthy soil biology. There are some techniques and tools, however, that can help speed up the process of increasing microbial health and diversity: cover crops, compost and biological inoculants.

Cover crops

Growing a diversity of cash or cover crops year-round is the gold standard for building healthy soil. In addition to fulfilling the principles listed above, plant roots help alleviate soil compaction by penetrating deep into the soil. Those roots are incredible sources of stable carbon, remaining in the soil long after surface plant residues have broken down.

Diversity is important. A large diversity of microbes already exists in your soil, but they are often dormant, waiting for the right conditions to stir them into action. Each plant family has specific connections with certain microbial species, so when plants are grown as monocrops, they only have access to one pool of microbial resources.

Prolific cucumbers growing in a bed of gorgeous mulch left over from a crimped cover crop.

Prolific cucumbers growing in a bed of gorgeous mulch left over from a crimped cover crop.

However, when many plant families are grown in close proximity, the numerous microbial communities join together to become a brilliant, multi-lingual super-organism. The magnitude of influence this microbial collective has on each other and on our plants is profound and spans well beyond nutrient and water acquisition. Microbes help plants deter pests and diseases, mitigate drought and flood conditions, adapt to cold and heat stress, and so much more that we have yet to discover.

Interplanting (also knowns as intercropping) is a great way to increase diversity within your plantings to help encourage microbial mingling. Furthermore, when combining short season crops with longer season companions, profitability within each bed can be maximized.

Here are a few interplanting combinations that have worked really well for our farm over the years: Lettuce with: tomatoes, peppers, long season brassicas, parsley. Scallions with: tomatoes, lettuce parsley, peppers. Cilantro with: long season brassicas, which is perfect for cutting once and letting the second flush of growth flower to attract beneficial insects. Radishes and turnips with: tomatoes, peppers, and squash. Beets with: tomatoes, peppers, and parsley.

Cash crops as cover crops

If your farm plan does not easily accommodate cover crops, you can still reap the benefits of cover cropping with innovative management of your existing cash crops. Instead of tilling in spent crops to prepare for your next planting, you can flail mow or cut your plants off at the soil surface after harvest. This leaves the root residues intact (great carbon sources) and is an effective way to transition beds without tillage. We transplant immediately to help maximize photosynthesis.

Initially, I was worried that root residues would impede seeding or transplanting of the next crop, but we have not found this to be an issue. I try to offset transplants from the previous crop, and if direct seeding, I try to ensure the previous crop was cut just below the soil surface to allow our seeder to pass through cleanly. Note that large amounts of leaf and stem residue from brassica family crops can have an allelopathic affect on your next crop. Removing crop residue from brassicas is recommended, although roots left in are okay.

Cover crops for all seasons

How to use cover crops on your farm is a vast subject and well beyond the scope of this article. Daniel Mays does a phenomenal job outlining multi-season cover crops in his book, The No Till Organic Vegetable Farm. An excerpt was published in the Nov/Dec 2020 GFM, “Cover cropping in no-till systems,” with a bounty of helpful tips on timing, crop selection, and termination techniques to help you find the best cover crop system for your operation.

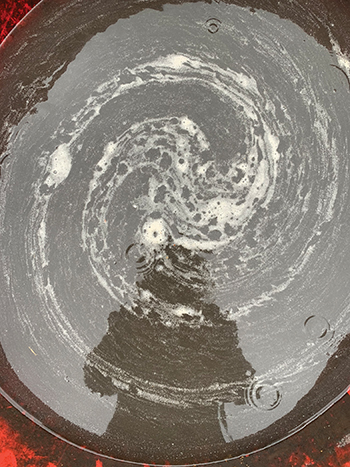

Biological goodness: A concoction of kelp, mycorrhizae, and fish emulsion for greenhouse starts. Getting greenhouse plugs inoculated early is a great way to introduce beneficial biology while transplanting.

Biological goodness: A concoction of kelp, mycorrhizae, and fish emulsion for greenhouse starts. Getting greenhouse plugs inoculated early is a great way to introduce beneficial biology while transplanting.

In 2021 we conducted a cover crop crimping trial. I am very excited about crimping cover crops, which has shown promise even in our wet and cold Pacific Northwest climate. Crimping a cover crop checks all of the boxes — it helps maximize photosynthesis, keeps the soil covered, reduces soil disturbance, and increases plant diversity. It takes about 10 minutes to crimp 100 linear feet with two humans and a t-post.

We tarped the area for two weeks afterwards to ensure crop termination, which worked really well. We were left with a gorgeous bed of mulch that we planted a late succession of cucumbers into. Last summer was a scorcher, and the mulch was incredible at keeping precious water reserves in the soil. That said, the mulch may cool soil too much in some climates, so planting a crop that prefers cooler temperatures, such as lettuce or brassicas may be an option to consider.

Compost

Compost is synonymous with soil health for many growers. The benefits of adding compost are well documented and include the following: improving soil structure, increasing soil organic matter, supporting soil microbiology, and providing a slow release of nutrients. However, the subject of compost has grown more complex over the years and it’s important to understand not only the sources of compost that are available, but also what we hope to achieve with a compost application.

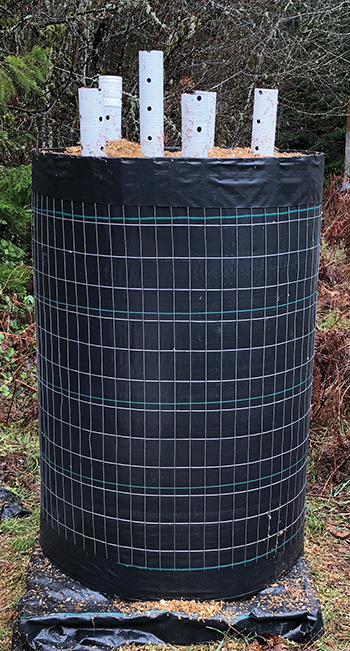

The Johnson-Su Bioreactor, a passive, fungal-dominated compost system.

The Johnson-Su Bioreactor, a passive, fungal-dominated compost system.

Not all compost is created equal. Making good compost is like learning how to make really good bread. The first several loaves may not turn out great, but you’ll learn a lot in the process. With compost, however, you’re cooking with nature and the ingredient list changes each time you make it. The cool thing about making your own is you have greater control over producing a product that will better address your soil’s needs.

The methodologies of making good compost vary greatly, but the following are a few suggestions that can help you find a system that works best for you and your farm.

Static Pile. By far, the simplest compost pile to make is a static pile that consists of farm debris heaped up and left alone for a year to decompose. The pile does not heat up enough to kill pathogens or weed seeds, so you need to be aware of what you are putting into it.

We built a 40 foot long, 3 foot high windrow with a huge diversity of materials, mostly farm scraps with lots of chicken coop bedding mixed in. We put a tarp over it and left it alone for a year. I was surprised at how awesome the biology looked under the microscope. I tend to use this compost for compost extracts (similar to compost tea, minus the aeration and food inputs), which strains out any weed seeds that may have been mixed into the pile inadvertently.

Fungal Dominated Compost. Compost made with a high Carbon to Nitrogen ratio can help support and increase fungal populations, which are typically lacking in most agricultural soils due to excess tillage. Dr. David Johnson and his wife, Hui-Chun Su, came up with a brilliant solution to this fungal dilemma. The Johnson-Su bioreactor is a passive composting system that creates a product with concentrated fungal populations that can be applied to agricultural fields at a low rate. You can learn to make one of these here: tinyurl.com/yc5d4ujh.

Biologically Rich Compost (Aerated and Turned). Aerated turned compost piles require practice and dedication. A diversity in plant materials results in a diversity of microorganisms and dictates how well your pile will heat up. Managing temperatures with well-timed turning (which keeps the compost from going anaerobic) can create an exceptional quality compost that has a high concentration of beneficial microorganisms.

Photo of my crew member after turning our biologically rich compost pile. Turning compost by hand is a lot of work!

Photo of my crew member after turning our biologically rich compost pile. Turning compost by hand is a lot of work!

However, getting the recipe just right can be a challenge and substantial yields can be difficult to achieve on a hand scale. This type of compost is excellent for compost teas, extracts, and inoculating potting mixes.

Aerated Static Pile (ASP) Composting. A static pile that uses a bouncy house blower to aerate compost? Count me in. Check out Jay Armour’s January 2019 GFM article, “Static aerated compost pile heats right up without turning”. There are many different takes on this style of composting, but overall, I love how it has the potential to produce a lot of compost that is biologically rich, reaches temperatures high enough to kill weed seeds and pathogens and does not require turning.

Commercial Compost. Inexpensive compost products can be purchased in bulk. While this option may lack a diversity of biology due to high temperatures and frequent turning (frequent turning disrupts fungal populations), this type of compost can increase soil organic matter, support soil microbes, and help to improve soil structure. It’s important to consider your source, as you are introducing materials from potentially unknown origins.

Quality. It’s not my intention to soil your perspective on purchased compost (terrible pun intended), but I’ve started to question products from large commercial or municipal sources. Recent excitement around improving soil health has many growers turning to compost to help facilitate soil improvement. Please don’t get me wrong, there are definitely quality compost facilities out there. Yet, it’s wise to be aware of potential risks of persistent herbicides in compost, and in certain compost materials, such as hay, straw, manure and livestock bedding. Be aware of the risks and know your source.

Is OMRI or NOP Certified enough? The regulations and testing around composting are not as rigorous as growers would like to think. While researching compost products, I learned there is no guarantee that a purchased product is free of persistent pesticides (which include herbicides, fungicides, insecticides, etc.).

I reached out to OMRI (Organic Materials Review Institute) for clarification on the issue and they said: “OMRI reviews compost products to the USDA NOP (National Organic Program) guidelines. Those guidelines currently do not require testing for persistent pesticides in compost feedstocks or the final product. They are aware of the issue, but no action has yet been taken to change the guidelines. Therefore, OMRI Listed compost may contain persistent pesticides brought on by feedstocks depending on the feedstocks used by the manufacturer.”

I highly recommend Doug Collins’ January 2003 GFM article “Clopyralid will be a problem for the foreseeable future” that covers persistent herbicides in depth.

Soil inoculants

The subject of soil inoculants feels a little like opening Pandora’s Box; tinkering with soil biological systems makes me a little nervous. That said, modern agricultural practices have severely compromised life in our soils, so if we can hasten the healing process by adding a few biological concoctions (while adhering to the basic principles of soil health), then why not?

Inoculants are materials used to increase microbial abundance and diversity in the soil. Researchers are barely scratching the surface when it comes to inoculants, so my hope here is to introduce readers to the topic and offer a few suggestions and insights. What’s covered here is far from exhaustive and the rabbit hole of information is long, winding, and totally fascinating.

Let’s start with a few considerations: Introduced microorganisms compete with existing organisms already in the soil. They need to find food and ideal environmental conditions in order to survive. Fluctuating soil moisture, fertilizers (both organic and chemical) and cultivation can stress introduced microorganisms and limit their success. If purchasing live inoculants: obtain products from reputable companies, expedite shipping (1-2 days), keep inoculants in a cool place (preferably the refrigerator), and once mixed, use as quickly as possible. Be aware of basic safety precautions and follow label directions.

Mycorrhizal fungi improve access to water and nutrients by colonizing plant roots and extending their hyphae far beyond the root zone. Other benefits include increased pathogenic resistance. Studies show inoculation of tomato plants led to increased resistance to fusarium as well as early blight in tomatoes in comparison to non-inoculated plants. Furthermore, research suggests that mycorrhizae helps improve soil structure, increases crop yield, and improves transplanting success.

We purchase a water-soluble product with several strains of endomycorrhizae (Myco Apply soluble Maxx) and water our greenhouse starts with the solution several times before transplanting out into the field. (Note: we do not inoculate our brassica or amarantheacea crops.)

Trichoderma. This bright green mold found in forests and agricultural soils is most known for its ability to combat plant pathogens. Studies from around the world demonstrate Trichoderma’s ability to control damping off, phytopthera, fusarium, rhizoctonia (root rot), and thielaviopsis (black root rot). Increased root growth and yield, along with improved tolerance to cold stress and drought are additional benefits. Sound too good to be true? Maybe, but with our cold and wet spring soils here, this inoculant is super exciting.

Rootshield Plus is available for purchase from BioWorks and includes two well studied strains: Trichoderma virens and Trichoderma harzianum. While some strains of Trichoderma have shown to be antagonistic toward mycorrhizae, these two strains are complimentary with mycorrhizae. We’ve also used a product from Arbico Organics called Mikro-Myco, which has mycorrhizae, Trichoderma, and Rhizobacteria

Aerated Compost Tea. While compost teas are one of the most well-known microbial inoculants, they are also the source of ongoing debate. While growers sing the praises of compost tea, some researchers continue to claim that the benefits have not been properly substantiated. From a biological standpoint, compost teas make sense. When the soil’s biology is intact, microbes should be everywhere — in, on, and around the roots, as well as on the stems, leaves and fruits. This biological sheath, helps protect plants against pests and diseases and increases nutrient acquisition, resulting in increased vigor and yield.

Aerated compost teas are derived from microbial rich compost. They are brewed with water, aeration, and often various microbial foods, such as molasses or fish hydrolysate, which feeds and increases the tea’s biology. The goal is to brew a concentrated inoculant, with high levels of microbiology, which can then be applied to the soil, or as a foliar spray.

Admittedly, compost tea has not been my go to for soil health. The process of making tea takes equipment (money) and monitoring (time), both of which I am always limited on. For some folks however, the process is an important part of their soil health regime. As long as you can start with a high-quality compost, teas can help bolster compromised microbial populations. Troy Hinke is a phenomenal educator and compost tea expert. You can find him on various podcasts and on YouTube to learn more about his methods.

Kelp (Ascophyllum nodosum). New research substantiates kelp’s potential to not only help improve our plant’s resistance to environmental stresses, but also to support microbial populations by encouraging plants to excrete more exudates.

We use a water-soluble kelp extract in the greenhouse (Soluble Seaweed Extract, my local grow supply packages this up into 4# containers. There is no brand name listed…). It’s pricey, so I tend to use it before and after extreme weather events. I also use it on our higher-end crops like peppers and tomatoes to get them off to a stronger start. Anecdotally, I have seen incredible response in lackluster plants after a kelp application.

Other Inoculants to Consider: Indigenous Microorganisms (IMO) are rooted in the principles of Korean Natural Farming developed by Master Han Kyu Cho. Jesse Frost does a great job outlining the topic in the November 2021 GFM article “An Introduction to Korean Natural Farming.” Biochar is introduced in Kai Hoffman-Krull’s May 2019 GFM article, “New research on biochar and carbon farming.”

Clearly, one size does not fit all. Fixing our broken agricultural system may seem daunting, but there is hope. While there is not one succinct solution for every farm, we have many tools that can be tailored to our unique farming operations. Our job as farmers is difficult already, and adapting to new soil health practices can feel overwhelming. My advice is to start small. Trials can be tweaked and built on each season. Small farms may consider starting a new protocol with just a few beds, while larger farms may entertain allocating a small block to experiment with.

Remember that soils and microbes are forgiving. Adhere to the principles of soil health the best you can. If it’s not perfect this round of crops, be kind to yourself, and remember to enjoy the process of learning the language of our soil. It has a lot to teach us if we are willing to listen.

Jen Aron has been a farmer and educator for the past 12 years and currently lives and farms at Blue Raven Farm in Corbett, Oregon. Jen is passionate about soil health and offers classes, consulting, and full-day workshops. You can find her at blueravenfarm.org and on Instagram @blue_raven_farm.

.png)