Different members of the onion family for different seasons

It is the heart of allium appreciation season here on our farm. Those cute little buggers start out looking like blades of grass and end up filling crates in the storage rooms and walk-in coolers, giving meals all winter a savory delicious flavor. No dish would be as good in the kitchen without some alliums. I think perhaps no farm is as good as it could be without them either.

Garlic

Here is a peek into the world of alliums and how we grow them at Muddy Fingers Farm. Let us start our stroll with the garlic. Lovely, spicy, steady garlic. It’s already planted when things wind down for the fall and pops up in the spring when the daffodils do, helping to remind us that the season is on its way.

In our zone 5 Upstate New York farm we plant garlic in mid-October. Scapes are harvested in mid-June and are nice additions to the early season CSA share. Bulbs are harvested in mid-July. We lay them in our barn on slatted greenhouse tables to cure. We trim them once dry or whenever we need the space or find the time.

Multiple onions per hole may decrease the size of the individual onion but increase overall yield due to increased planting density.

Multiple onions per hole may decrease the size of the individual onion but increase overall yield due to increased planting density.

We plant three rows per bed on 42-inch beds. Years ago we drove by a neighbor’s farm and saw they had planted garlic on black plastic. We tried it and were impressed that the scapes come up a little earlier and liked how the dark color warms the soil in the spring.

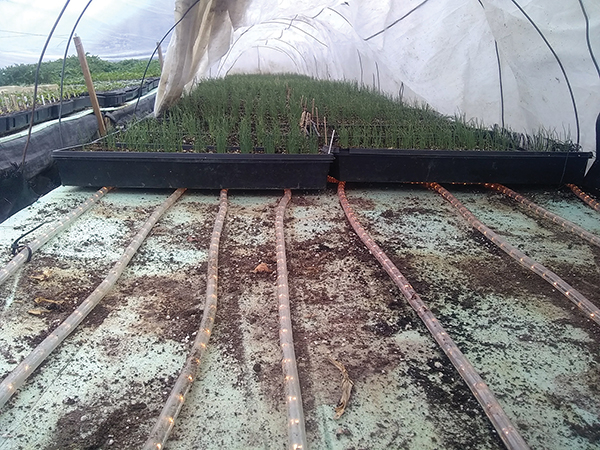

Alliums on rope lights for bottom heat.

Alliums on rope lights for bottom heat.

We have tried both black plastic and landscape fabric; we prefer the landscape fabric since we can reuse it. We use 4-foot-wide landscape fabric with holes cut about every ten inches. We plant three cloves in each hole. Planting so densely reduces the size of the bulbs but increases overall yield. We’ve been able to reuse this landscape fabric for many years and thus far haven’t had any disease problems.We protect the garlic with row cover before the ground freezes and then pull the covers off when the plants start to grow in the spring.

A basket full of tall Lincoln leeks. And, yes, the author is kneeling they’re not THAT tall. All images courtesy of the author.

A basket full of tall Lincoln leeks. And, yes, the author is kneeling they’re not THAT tall. All images courtesy of the author.

Scallions

Next in the allium family for us are scallions. We’ve grown the small green onions used for bunching in two different ways. A friend’s farm turned us onto planting onion sets as close together as possible, mulching deeply and harvesting the greens in the spring as scallions. This system was fun, but we’ve had trouble sourcing certified organic sets. And though we hoped to thin the sets and sell some as scallions and some as bulbed onions, the onions just bolted before they bulbed.

So, for the last few years, we’ve planted scallions from seed in small plantings in 2-inch chain paper pot trays (264 cells per tray) and transplanted six plantings with seven rows per bed over the course of the season. We find that four trays in each planting is enough for our small farm. Too many more and their quality decreases before we can sell them. So we try to have another bed ready to go when that happens. We’ve only used “Evergreen Hardy White” as the seeds are inexpensive and they make fine scallions for us.

Leek flowers.

Leek flowers.

Next we come to our red whale — shallots. We generally sell onions for about $2.20 per pound, leeks for about $3.25 per pound, but we can easily charge $6 per pound for shallots, so we’re hungry to produce those gourmet little onions.

We’ve grown them from sets both planted in the fall and in the spring without much success. We have bunched the plants that were fall planted and sold them as shallot-scallions. But they often bolt before they are even big enough to do that. (See the article “Shallions, bulbs, and edible flowers: Three crops from one fall planting of Dutch shallots” from the January 2021 GFM for more on shallions.)

In general, we like to start all of our alliums (excepting garlic) from seed in mid-March. But boy, shallots are plagued with such poor germination. The ones that come up seem inclined to easily get diseases and die in the tray. They tend to grow slowly and be very susceptible to getting water logged in the trays and the plants can suddenly turn yellow and experience tip die-off.

Allium leaf miners and their damage.

Allium leaf miners and their damage.

We also realize that our somewhat poorly drained clay loam is not ideal for shallot growing. But the price per pound and the flavor, oh baby, keep us on the hunt to conquer our yellow or red (we’re not picky, we just want shallots) whale. We will try growing them on raised beds next year.

Onions

Now we’re into our main crops in the family field: The onions. We grow three types- early fancy types for bunching, sweet, and storage. Because onions aren’t good competitors with weeds, we grow them on large swaths of wide landscape fabric covering several beds and their permanent paths. This keeps the crabgrass out of our normally weedy pathways.

We found that we didn’t like to grow them on biodegradable plastic. The number of holes in the plastic made it degrade too quickly and weeds became an issue before the plants were ready to harvest.

We plant three plants per hole (except for sweet onions) and now use three rows per bed with holes about 10 inches apart. We have also planted onions at four rows per bed and two plants per hole. We are fitting slightly fewer plants per 100-foot bed (1,200 in the four-row system verses 1,080 in the three-row system), but it is much easier to plant and maintain. And the onions get larger at a slightly lower density. This has been an extremely positive change on our farm.

Leeks

The last stop on the allium express for us is the best stop. We love our leeks; we tend to sell them for about nine months of the year and they fill us with such joy.

Our first true love is the early season or bunching leeks and this is where my deepest fondness lies. We grow tall light green (rather than blue green) leaved leeks for most of the season until it gets too cold for them (temps in the mid 20s). Then we switch to the hardier winter leeks.

For the early season leeks we love both “Lincoln” and “Bulgarian Giant.” We start them in open 10x20 trays in March with about 300 plants in 10 rows. We normally have leeks on the table top in our greenhouse that is only heated with rope lights, giving them bottom heat. Each night we cover them with row cover. If it’s very cold, plastic, too. On extremely cold nights we will put a small space heater under the tables to help bring the temperature up a little more.

We transplant out into landscape fabric in a dense planting of four rows with holes about every 8 to 10 inches. We plant four plants into each hole — three in a clump and one separately, making sure the one separate leek’s roots aren’t intertwined with the others. As we harvest, we thin for baby leeks by pulling the three planted together and leaving one single leek in each hole.

Leeks covered with insect netting to exclude allium leaf miner.

Leeks covered with insect netting to exclude allium leaf miner.

It is slower transplanting in this way, but we are basically double-cropping the bed, one bed of baby leeks and one bed of big leeks all planted at once. By the time we’ve finished thinning out the beds, the first leeks are large enough to sell as single leeks by the pound.

These early leeks are fantastic and we’re so sad to see them go when they are done. We’ve grown “Lincolns” as tall as myself (5 foot 4 inches) when the greens are stood up to measure. And they’ve weighed in at as much as two pounds in the past (at $3 per pound that’s a $6 leek).

So, when we heard a rumor that “Lincoln” might be dropped by the trade, we were scared. “Bulgarian Giant” is quite similar and is open-pollinated. So, we started growing that variety and producing our own seeds, just in case.

Growing leek seeds

Growing our own leek seeds has been a really fun new layer in our love of leeks. We leave 100 to 150 nice leeks in the bed at the end of the season. We row cover them and leave them out in the weather. The plants lie down over the winter, and when we uncover them in the spring, they look like a bunch of slimy, silver snakes on the landscape fabric.

The first year our hearts sank and we figured we had messed up and should have brought them into the cooler for the winter and replanted them in the spring. But as the days get longer, those plants will stand back up and start growing. Out of those disgusting snakes emerge the most lovely white and purple cluster of flowers that are irresistible to all sorts of insects.

It’s not unusual to walk by and see three or four different types of flying insects (bumblebees, native bees, mason bees, wasps, and yellow jackets) on each blossom. Even people find them fascinating. We had a new pond built this year and they caught the eye of the operator driving by on equipment. They stopped to ask what those big balls on stalks were.

They flower for a very long time and it takes ages for the seeds to mature. The first year we grew them, “harvest leek seeds” was on our to do list for about 10 weeks before it was actually time to do it. Once the seeds seem mature (have turned black), we harvest the whole head and put them in a bin or bag. We shake the seed heads into a bag and then plant in open trays in the spring.

Allium leaf miner

Our love affair with leeks used to be a pure unsoiled thing, but in the last few years, it has started to be sullied. There is (sigh) a new pest, and it has arrived to ruin our blissful union. The allium leaf miner is here and it does some real damage to the perfect aesthetic we’re used to from our tall slender friends.

In the old days, leeks came out of the field sometimes looking gross, but we’d peel off an outer layer or two and they’d be pristine, glistening up to two feet of clear, clean light green shafts with the faint white hue underneath. But since the arrival of allium leaf miner that old trick of peeling anything bad away has been replaced with a terrible new reality: the leaf miner damage gets worse the deeper you go. So now instead of peeling a layer off being the most amazing joy, it is the most depressing revelation — only more and more grubs inside.

The first year we had a population that reduced our ability to market the leeks was 2020. The early leeks were okay but as the season went on, the damage was bad enough that in December 2020 we just stopped selling leeks and abandoned the rest in the field.

In and effort to get a head of this new bug(ger), we tried both non-spraying organic solutions that we had read about: silver reflective mulch and insect exclusion cloth. Due to heavy swede midge pressure, we were already very familiar with using insect exclusion cloth. We use ProtekNet. This year we got the 47 gram which has a longer life expectancy. We’ve also used the 25 gram and it lasted several years, but we wanted to try the 47 gram for its longer life.

We transplanted the plants into reflective silver mulch. I guess the glare discourages the adults from landing on the leeks, and at the right angle you could just about blind yourself. Several weeks later, we weeded the leeks and covered the plants with hoops and insect exclusion cloth.

It was our hope that this year with these precautions we wouldn’t have any allium leaf miner damage. The early season leeks were very clean. But the winter leeks had damage. Less than last year but as of this writing in early December, they are about to be abandoned in the field again. Even if it’s only one or two larvae rather than six to 10, it’s still more larvae than most people want in their food.

We’ll try again next year. It’s possible that our dog, who jumped back and forth over the low hoops and cut open a few tears in the netting, might be responsible for this infestation. Or it’s possible that the insect exclusion netting just went on too late. It was late in arriving and then we were too busy to get it on for a while. Perhaps earlier application next year in combination with the reflective mulch will completely exclude the leaf miners.

Winter leeks

Winter leeks end our tour of the allium family. Once it gets down to the mid-20s, the early season leeks get too damaged. They become unsaleable and on their way to slimy snake status. We generally aim to just finish harvesting before the weather reaches this point.

For our latest leeks of the year, we switch to a blue-green leaved variety and leave them in the field for as long as possible. We’ve grown lots of winter hardy varieties and haven’t found any that wow us like “Lincoln” does. Winter leeks tend to be much better rooted and can be hard to pull and they always seem to be smaller with much less shaft area than the early season leeks. We have grown “King Richard,” “Siegfried,” “King Sieg,” “Lancelot,” “Blue de Solaise,” “Tadorna,” “Bandit,” “Megaton,” and this year “Jumper.”

If truly cold weather is approaching, we have pulled winter leeks and stored them in the walk-in cooler as well, but not very often. We’ve also just left them in the field under row covers. We manage to have a pretty good supply of leeks for most of the year. And with onions, shallots and garlic in storage, there’s always some magical allium to go to market and make the start of a great meal. Thank goodness.

Good news, those leeks we abandoned in December 2020, we harvested in June 2021, totally having forgotten why we left so many leeks in the field. Somehow, they were immaculate inside. The leaf miner larvae were gone and the damage was healed up as well, giving us some quite early leeks. We’ll see if the same holds true this year, fingers crossed. Maybe 2022 is the year we don’t have to abandon any leeks in the field.

Liz Martin is half of the team at Muddy Fingers Farm together with her husband Matthew Glenn they grow two acres of certified organic vegetables for CSA, farmers market and fine local restaurants. They use a permanent bed system and 2022 will be their 20th growing season! You can find them on Facebook and Instagram if you’d like to connect.

.png)