“It’s not me, it’s you,” I said as I fired a high-school-aged employee whom I had diligently tried to train and coax along. It was kind of a joke; it kind of wasn’t. He didn’t care that he got fired just like he didn’t care if I asked him not to lay down while weeding nor not to sass my mom who was helping out.

That year I started with five employees, fired one, two quit, and ended with two terrific folks. They both worked for me for a few years. This year I was faced with creating a new crew from scratch. I worried I’d never be able to find and create another wonderful crew, but had another delightful, smart, effective team. The four of us — Savannah, Brian, and Brandon and I — have spent a lot of time discussing across the lunch table and across the rows what makes a good farm team. We’re sharing what we’ve learned.

Tips from Nella Mae, farm owner

Employers should ask themselves: “Where would you want to work and under what conditions?” One of my best experiences was becoming a farm employee again after my first two years as a boss on the farm. I worked for a local goat dairy for the winter for some extra cash. I loved the job and the farm owners, and I learned a lot about how to be a farm employer. This experience brought into stark relief what makes farm work great (like goats) and what makes it hard (like frozen machines at 3:30 a.m. with no system to get help).

From left to right, the authors of this article- Brian, Nella Mae, Savannah & Brandon helping harvest hemp at Brian’s family farm

From left to right, the authors of this article- Brian, Nella Mae, Savannah & Brandon helping harvest hemp at Brian’s family farm

I took note of what I learned through the winter and decided to create a place I would want to work and to work toward making it better every year. All of the lessons I learned are simple things, but together they create the foundation of our team and workplace. Here are my lessons.

Plan. Farm teams coalesce when the work is organized and knowledge is shared. I prioritize making a plan and having tools ready to go before folks show up. I let everyone know what the draft plan is for the day, the top priorities and why they are at the top, and what to do next if I am not around to discuss things. However, I’m not wedded to my plan. I have information about customers my co-workers might not have, but they have information about aphids I might not have. We create the final plan together to fit the needs on the ground.

Tools. It is easy to get irritable with each other when it is hot and you don’t have what you need to do a job or you get the hoe with the sloppy handle. I once worked at a farm where I could not find a shovel reliably, and honestly, this made me angry at the farm owner. I find that providing plenty of tools, and reminding folks to put them away at the end of the day is a simple approach that avoids friction and frustration and keeps folks happy.

I make sure to take the time to show everyone how to use each tool properly and to provide time for maintenance. I also ask folks regularly if there is something they need but don’t have. We all have preferences, so a variety of tools is great. Some folks want to cut kale bunches with scissors and others with a knife.

Let people accomplish tasks. I have heard from many farm employees that it can be endlessly frustrating to be taken off tasks before they are finished and moved to new ones. I have found most people like to have a sense of accomplishment at the end of the day.

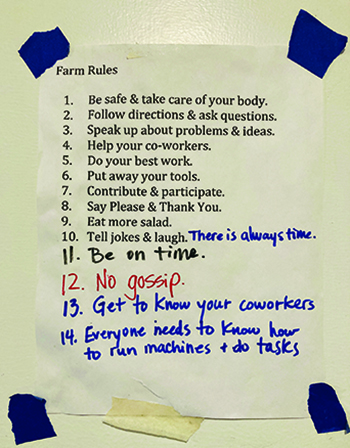

Farm rules developed by farm teams over the years. The last one was added by this year’s team

Farm rules developed by farm teams over the years. The last one was added by this year’s team

Reasonable hours. Farm work is hard. I would argue that most folks (including me) can do about six to seven hours of effective farm work. I would rather have seven fully effective hours than 10 with the last three miserable, demoralizing, and slow. I argue that it may be more effective to hire four people for seven hours per day (28 hours) than three people for 10 (30 hours). If it is hot, freezing, or folks are low energy, sometimes we finish the last hour inside sharpening tools, cleaning or other jobs that don’t boil your brain. We always have music or podcasts or conversation.

The start time matters, too. The last few years I set the start time with the crew. A few years ago they wanted 6:30 a.m. The last few years it was 7:30 a.m. or 8. I’d rather start at 8 a.m. than be angry every morning when they don’t show up at 6. This year we were back to 6:30 a.m. I want a happy crew that shows up on time and doesn’t leave completely beat. I want the schedule to work for them, and for me it isn’t a big deal to make adjustments to mine.

Little considerations go a long way. I learned from my neighbors who own a nursery that having snacks and drinks available is a much loved perk. If folks seem tired, I’ll bring out mugs of Nescafe — small considerations don’t have to be fancy. I feed our team a hot, homemade farm lunch on the two harvest days of the week, which means they don’t have to pack a lunch.

I like doing this because I felt that a lot of my own farm employee experiences lacked tasting the food we grew. It is a little extra work, but I’ve become fast at slinging a lunch out and the crockpot is my friend. Farm lunch mostly takes planning ahead.

There are other considerations that make folks feel a part of the farm and the team. I want employees to feel welcome to bring out friends or family. Another farmer I know pays $5 if folks carpool and has a chips and dips party for each employee’s birthday. Of course, everyone gets mountains of produce and plants. These things are cheap but go a long way to make people feel appreciated. I think folks who are appreciated make better team members — they are easier to lead and to work with.

Let folks know why you do things the way you do. It can be frustrating to employees to be asked to do something in a way that seems, well, stupid. A friend of mine worked on a farm where they had to untangle wads of cotton string for trellising each year. The mindlessness and futility of jobs like this can hurt morale. Buying new string would have saved time and given employees a sense of accomplishment when they spent the day trellising instead of untangling. But there are other things that we learned through trial and error that work best a certain way because of soil type or customer preference or a finicky pump. Folks are fine doing things how I suggest as long as I give a little history and explanation and when I’m open to their suggestions for improvement.

The team pulling new plastic over a greenhouse.

The team pulling new plastic over a greenhouse.

Teamwork means creating a shared sense of contribution, responsibility, and meaning. The buck stops with me when it comes to mistakes. Mistakes are almost always due to my lack of explanation or planning. But even if they aren’t, it is easier for me to make a quick, kind course correction and take responsibility for mistakes. I lose nothing and I don’t harm morale.

On the other hand, I do my very best to consider and put up for discussion ideas for improvement. Sometimes I can get attached to the way I do things. Fresh eyes and a beginner’s mind are invaluable. My farm’s systems are excellent precisely because the folks I work with are smart and generous with their ideas, and I listen and try them out. Folks really love feeling a part of the decision-making and problem-solving of the farm.

Attract good employees and keep expectations reasonable. My uncle was a ranch foreman for years. When I started my farm he told me, “Nella, never expect the folks who work for you to do more than 50 percent of what you do. If they do more, that’s gravy.” No one can or should work the hours you do on your own farm.

But of course, not everyone is a good match. Another farmer once told me, “You know within two days if someone will work out, so there is no use in hoping they will grow into farm work. If not, get it over with, pay them, and let ‘em go.” I have found it is easier to do this earlier than later.

The author is on the left with a past intern at the farmers market.

The author is on the left with a past intern at the farmers market.

I have attracted good employees because my farm has a good reputation both in what we grow and how we treat people. We hire people who are a good fit on the team, rather than experts at farming.

Pay better wages. Farming can be a hard way to make money, but I think good wages are key. If you want to attract and keep good employees, you have to figure out how to pay them well. Sometimes I do the math in my head. I know I am paying myself much less per hour than the folks who work with me. But they allow me to avoid harming my body and my relationships through overwork and allow me to enjoy the place I live, and even take some time off.

Get to know and care about your people. I haven’t vibed with every coworker, but I do my best to get to know them and make a real connection. Our crew is small, so I make sure that we have time to both work as a team and work one-on-one together weekly. I think this builds rapport and sparks interesting conversations and new ideas. I get to know the people who are working with me to feed our community, tend the land, make money, and enable me to leave the farm occasionally.

Gratitude, gratitude, gratitude. “Look at these beautiful bouquets of beets!” “Thank you for your hard work today. I know it was frustrating, but we persevered! Let’s knock off early.” “Thank you so much for taking care of things while I was gone!” “Wow! Let’s go appreciate the growth of that cover crop you put in last month.” “Thank you for your leadership today. I really appreciate how you step up.”

Tips from Savannah

Start off on the right foot — in the interview. I gave Nella Mae a ride to town one day to pick up her truck at the shop, and we got to talking about how things were going on the farm. She was asking for feedback and I know what I said surprised her. I told her one way we started off on the right foot was in the job interview.

The author’s daughter bunching scallions with a past crew. All images courtesy of the author.

The author’s daughter bunching scallions with a past crew. All images courtesy of the author.

I was really impressed that Nella Mae laid out her expectations of employees during our first conversation and that she asked me what my expectations were of my employer. I had never been asked that before. Nella Mae was the first boss to ask, “What can I help provide you if you were to take on this position?”

I never had a working relationship be mutually beneficial for anything besides a paycheck so this question was humbling to hear. Being a young, future farmer, I joined this position hoping to gain knowledge and a sense of my future workplace. I didn’t need to ask for that mentorship aspect of the job because Nella Mae was already questioning my expectations as an employee.

It was a convenient way to bring up that I was looking for a leader, teacher, and mentor while working. Not only did this interview question give me reassurance that I was in the right place, but it gave me a deep sense of pride knowing I was going to contribute to a team that had no hierarchy or judgment and allowed me to make mistakes and learn from them.

Why belong to only a team? Belong to a community. It was an unseasonable 100 degrees in June on my first day. I was hot, tired and mentally trying to prepare myself for the grueling work that was headed my way for the summer time. Around 1 o’clock, Nella said the most glorious words I think anyone could have said, “Let’s get out of the sun.”

Nella and I drove together over to a neighboring nursery where I was introduced to community members, other farmers, and my new co-workers who also worked at the nursery. Working on the farm this summer I met many new people, including a water witch, a mushroom hunter, hippies and musicians. It is safe to say Nella threw the whole kitchen sink at me as far as people go.

People stopped me on the streets, farmers markets, and on our local college campus to ask about my work at the farm. Working on the farm team gave me a sense of belonging in a community that was not my own and held me accountable for the work I enjoyed doing. Meeting new people in agriculture helped me realize the impact we at the farm had on the businesses, lives, and land of others. I never had to mentally prepare myself for the severe heat again because having a sense of pride in the work I was doing for others made it all worth it.

Having some wagon fun. There is always time for fun

Having some wagon fun. There is always time for fun

Tips from Brian

Boost morale and efficiency. “Everyone needs to know how to do it.” When I started working with Nella Mae at her farm, I was a little intimidated. I had never worked on a farm before. Most of my work experience was in a healthcare lab setting. I quickly noticed some differences in the teaching style between this new job and my last one.

In my old lab position, I was taught how to do one task really well, but I was the only one who knew how to do it. I was doing the same task day after day and could never be absent because no one else was trained. Working with Nella, I appreciated her inclination to teach us more than one task. “You all need to get hands-on experience with this,” she would say. She wanted us to be proficient in all duties, rather than one person knowing how to do only their one job. If we didn’t understand how to do something, she would gladly teach us.

This was a great chance for me to learn, but this also served to build our team’s morale and efficiency. Since everyone knew how to do the jobs, we would be able to talk to each other about preferences for the day. Perhaps Savannah would pick tatsoi one day, Brandon would pick lettuce, and I would wash the produce. Each day, we were able to rotate jobs and not become bored with one task day after day.

If I would have had to be the produce washer everyday, I might have burnt out quickly. In addition, this helped us to see how others would do a task. Perhaps one individual was more efficient than the others and we could learn from each other.

Goodbye “Do as I say, not as I do.” Leading by example is one quality I have always appreciated. This comes in a couple different forms. Sure, I love it when a boss works right alongside you and shows you how it’s done. Instead of a boss saying, “Go do it this way because I said so.” Nella has always shown us why we do something the way we do it. However, it doesn’t stop there. She continues to do it the right way. She gets her hands dirty, too. She is in the trenches with us.

One boss I had used to tell us the right way to do something, but then he didn’t do it himself. Whether out of laziness or carelessness, it always struck a nerve for me. “If I have to do it, why don’t you?” This point might be obvious, but the boss is an equitable member of the team and should have the same rules for themselves as they do for their colleagues.

The less obvious leadership skill I appreciate is the freedom to ask a simple question: “Why is this way the right way?” Nella also routinely encourages us to ask questions. “Why are we doing it this way? Would it be more efficient if we did this?” It’s nothing personal. She is always trying to learn. She is always trying to do things better. If we have ideas, she wants to hear them. That, to me, is part of leading by example. It’s admitting that she is human. It’s admitting mistakes or the fact that there might be a better or faster way.

Tips from Brandon

Look for the enjoyment. It is rare to hear someone describe his or her job in a way that shows enjoyment. We often hear more about the unenjoyable parts of being part of the workforce: long hours, difficult conditions, sometimes-seemingly unfair compensation, and just the simple fact that we can’t sleep in. When I overwhelm myself with these aspects, I return to my motto: If it is possible to enjoy this, then I should attempt to.

I started looking around for things to enjoy and found a bounty. There are so many ways for me to engage at work. It isn’t hard to observe different insects and ask Brian, my biochemist coworker, what their role is in the ecosystem. It isn’t hard to ask my coworker Savannah how her classes are going. It isn’t hard to ask Nella Mae how she started a farm in the heavily male-run field of agriculture.

My best tip for building a team is to participate, to engage with your coworkers. Care about their day and their family. Engage with your field. Why do you do what you do? What purpose does it serve? What’s the history? If everyone found enjoyment in his or her job, workplaces would reflect it.

Standards that work for your farm

Each farm has to create its own workplace standards, tone, and environment. I want my farm to be familial and friendly because my farm is my home and I bring people into it. I find the act of growing food something very meaningful and personal. I am extremely community-minded, I care about mentorship, and I want to have close relationships with the people I work with day in and day out. This may sound like a nightmare workplace to someone else, but it works for my farm.

I have worked hard over the last seven years to lay a foundation and create a learning atmosphere in our workplace, but it is successful because my co-workers were fully participating in making a team. Savannah, Brian, Brandon and I created a great team this farming season together. The next farm team will be different and have a different dynamic, but I carry all the lessons from these smart, generous folks forward.

Nella Mae Parks farms on her family place in Cove, Oregon. She just completed her eighth season home, growing vegetables for her on-farm farmstand, the farmers market, and wholesale outlets in the region. Nella Mae is passionate about agriculture and building community. She is committed to mentoring and training the next generation of farmers and advancing equity and cooperation.

.png)