Two Wisconsin cheeseheads visit veg farms

Dear Reader, it’s nice to join you in the quiet of these pages. This issue of GFM is published in the heat of the season, which can be stressful and disappointing. At such a time it can be nice to take a trip far away from one’s fields, gain a little perspective, and also just get a break. If you’ve grabbed a few minutes and a comfortable seat, allow me to indulge you in a tale of friendship, adventure, and vegetables, in a land far, far away.

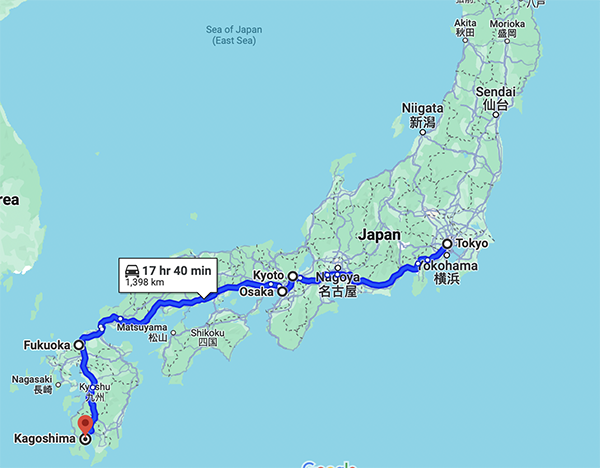

Our route of travel over three weeks, arriving in Tokyo, making our way down south to Kagoshima, and leaving back out of Tokyo. All images courtesy of the author.

For years my veg-head friends and I have been trading YouTube videos back and forth of Japanese vegetable tools. In such videos we saw what felt like vegetable science fiction — advanced robotic machinery designed for small-scale growers, running on immaculately formed beds of bespoke soil texture, operated by technicians in spotless clothing, all accompanied by a futuristic soundtrack of elevator-electronica music.

We were fascinated. Are these advanced machines common in Japan? How can Japanese farmers afford them? What other machines and techniques exist in Japan? Why are these machines not available to American farmers? What is the wider cultural system that the machines exist in? What is it like to be a Japanese vegetable farmer?

My dear friend Paul Huber is a farmer in Madison, Wisconsin. And over the years, as we planted garlic together, drove in the car to pick up machinery, or goofed off like 10-year-old boys jacked-up on pixie sticks, we discussed making a trip to Japan. Then, it just so happened that I was leaving a job and had some time, and he had some paid-time-off accrued.

Paul and Kamikura-san using Google Translate to communicate in her garden. Notice the finely-tilled soil prepared for planting.

We figured if we didn’t take the opportunity to travel to investigate the source of these vegetable videos, we wouldn’t get to it until we were retired old men with jaded attitudes. So, this past November, for three weeks, we traveled from Tokyo down south to the tip of Kagoshima and visited farmers all over the country. If you have the time, let me tell you about Japanese vegetable farming and the beautiful people we met.

Because our Japanese language skills are worse than the germination of old parsnip seed, we planned our trip meticulously over the six months leading up to it, seeking out any contacts in Japan who spoke English and would visit farms with us. Through this process we met American farmers and farm-adjacents who had experience with Japanese agriculture, as well as Japanese people who had agricultural experience with Americans. We structured our trip so that we could meet with the organic vegetable farmers that we had identified.

After months of planning the big day arrived and we bid goodbye to our supportive wives and skyed out of O’Hare airport in Chicago. Twelve hours later, upon arriving in Tokyo, the lights, speed, and scale of the city bewildered our blurry eyes.

Farmer Hikaru (left), and Kentaro Suzuki (right) in a hoophouse of chrysanthemum greens. Notice the high raised beds to avoid the high water table. Also, notice the red insect netting on the sides - we observed red-colored insect netting in hoophouses throughout Japan. The farmers and researchers said that red better repels insects because they can see red more clearly.

We enjoyed starting and ending our days in the public baths, walking under the giant cedar trees in the park, and falling in love with the food — stopping at all sorts of noodle shops where braids of fresh noodles were dropped into vats of boiling water and then combined with tasty vegetables and meat. After three days wandering around tourist sights in Tokyo and sleeping tightly packed in a capsule hotel, we had mostly gotten over the jet-lag and learned the basics of public transport.

Once we got our bearings, and accompanied by our new friend Saddy (to whom we were bound in the deepest bonds of friendship after singing karaoke and enjoying some beverages with him the night before), we took a long train ride to the far reaches of Tokyo for a garden visit. Along the way we peered out of the speeding windows at rolling acres of hoophouses covering mostly fruits — grapes, persimmon, and pear. Because they do not need to withstand snow load in that climate, their structures were cheaper to build and less substantial than what Paul and I are accustomed to in the Midwest.

After a short walk from the station through a dense residential neighborhood, we came upon a garden of three acres. There we met a smiling woman, Kamikura-san, whose joyous and piercing eyes and sun-wrinkled cheeks lit up her face. Hers reminded us of a large and well-tended community garden in scale and layout.

Our guide in Kyoto, Kentaro Suzuki, in a field of harvested rice.

We began at the compost piles, which had a prominent place in her garden. Kamikura-san was very intentional about keeping those piles fed. A main feed-source was leaves, collected in tarps from the hills above, or dropped off by her neighbors. Because they made her compost, she told us, “leaves are like money.” Kamikura-san also devoted a substantial amount of her space to growing Crotalaria (sunn hemp), a potent warm-weather legume, which she cut multiple times each year to feed to the compost piles. Her other fertilizer was crumbles of dried chicken manure, by far the most common fertilizer for the Japanese organic farmers we visited.

Kamikura-san toured us around the garden and we talked — which I would have thought impossible — but our shared love of plant kind and soil stewardship somewhat bridged the linguistic gap (which happened again and again with the farmers we visited). Kamikura-san introduced us to new vegetables and familiar ones. We observed how she gardened to create a place of joy and peace for the community.

The solarizing machine - tiller with clear-plastic layer on the back.

There were several long hedges of flowers whose only purpose was beautifying the landscape and filling bouquets. She told us about the classes and garden apprenticeships she runs for her neighborhood’s wayward youth. As we walked she collected herbs like roselle flowers, mint, and lemongrass. When we found ourselves at the top of the garden we sat at a table under the shady pergola looking out over all her plant-soil symphony below.

There we enjoyed the gentle conversation that passionate gardeners can have as we sipped garden tea. More than particulars like plant spacings or fertilizer rates, Kamikura-san shared her outlook. Instead of frustration, she found joy in the complexity of natural farming. “I love farming because I get to be a first-year student every year, so it’s a great fit for my life.”

From stateside we had connected with an organic produce wholesaler in Kyoto, and that is where we headed next. Kentaro Suzuki met us at a rural Kyoto train station in his delivery van and spent the day with us visiting organic farmers in the Kyoto area.

Field of organic spinach that has never been weeded - but solarized before planting.

Whereas Kamikura-san’s garden was an urban vegetable-only space, now that we were out on the rural agricultural landscape things looked different. Laser-flat fields were laid out along the river valleys, holding high raised beds (bed tops 13 inches above ground) formed on 5-foot centers. Crops in the beds were planted in close rows, i.e., four rows of carrots on a bed with rows 6 inches apart.

Soils appeared to be a mix of clay and silt and contained not a single stone. Narrow irrigation ditches lined the periphery of most fields. In looking more widely, they ran down from the mountain sides to the valley and finally into the river.

The agricultural landscape before us appeared much more designed than our Midwestern landscape of fields with treed fencerows, rolling topography, and stony or heavy clay soils. We were witnessing a sculpted agricultural landscape formed by communal work over centuries.

Vegetables on raised beds at Himarian farm, outside Osaka.

Kentaro explained: “The families living in the hills above this valley farmland have been there for 600 years. In the village of 45 families there are maybe two last names. They feel the weight and responsibility of their family and village histories to steward the land. They also have a long history of working together to form these lands. And they are still being formed. You can see the bulldozers down the valley, flattening out more land so it is all conducive to flood irrigation from the ditches, so that the water is collected as it flows down from the mountain and is guided into the fields and then drains off into the river.”

Later our new friend Shinya would tell us: “To understand Japanese agriculture you have to understand rice. Irrigated farming enforces cooperation between farmers.” Another farmer told us, “Rice is the foundation of our agriculture, then we apply those principles of cultivation to other crops.”

Paul is standing in the recently-harvested rice field, next to a pile of rice hulls, which are being turned into bio-char with this simple chimney burner.

With this rice-centric context we arrived at the farm of Hikaru-san, a younger farmer who grew up in the city, apprenticed with a noted organic vegetable farmer, and had been running his own farm for about seven years. As we arrived Hikaru stepped out of the packing shed where he was packing greens with three employees.

He showed us his greenhouses. Because some of his land drained poorly, the beds in his hoophouses (unheated) were very high so that the plant roots would stay dry. One hoophouse was solidly seeded with spinach — no rows or walking paths — but how did he weed a lawn of spinach with nowhere to walk or clear rows to weed between?

Hikaru pulled out a simple metal-tined rake, like we might use for leaves. He showed how when the spinach was young with maybe one true leaf, still taller and better-rooted than emerging weedlings, he had quickly, yet precisely, raked the surface once, killing some and dislodging enough weedlings that the spinach soon overtook any weeds and erased his footprints.

Solid-seeded hoophouse spinach that was weeded once with a tine-rake at ~first true-leaf. Notice the weeds in the understory, that do not compete with the crop and will not set seed before harvest. Also notice the internal shade-cloth at the ridge of the hoophouse, which can be rolled-out when needed.

In the photo you can see there are young weeds under the crop of spinach, but they are not competing with the crop nor going to seed, so no problem. Of course, timing was essential for this technique. This tine-raking technique was just a small glimpse into what we would learn a few days later when we met the master of tine-weeding, but I digress.

We walked away from the home farm out to his fields where we saw again the tall raised beds on 5-foot centers — this time with a mature weedless spinach crop blowing in the wind. Hikaru explained his use of solarization. The back of his 3-point rototiller was set-up to hold a roll of plastic, but whereas we might lay black plastic with such a machine, he formed beds with the tiller and laid clear plastic on them in one pass.

As he explained it, the solarization did two things: With the soil properly moist the plastic promoted “fermentation” in the soil that made more nutrients available to plants. When left on the soil for about 30 days in warm weather, the heat killed weed seeds near the surface. He then removed the plastic by hand, planted spinach with his precision push-seeder, and never weeded the crop. The clean organic spinach we were looking at had never been cultivated. He acknowledged the long time required for solarization and that he had to weigh the loss of 30 growing days against the perfect weed control we observed.

Closeup of the small weedlings that have sprouted under the solid-seeded, blind-cultivated spinach, which should not go to seed before the crop is harvested and the bed tilled again.

Like most organic vegetable farms that we visited, Hikaru-san grew both rice and vegetables. Much of the rice in the regions we visited had been harvested a few weeks prior. Once harvested, the rice fields grow vegetables during the off-season. On Hikaru-san’s farm, as on most others we saw, the most advanced machinery was not in the machine shed, but rather in the rice processing barn. Farmers growing on 10 to 30 acres had scale-appropriate and high-tech rice processing equipment to harvest, dry, sort, and package their rice. This means that they could produce consumer-ready 5 pound bags of organic rice right on-farm.

In learning about rice cultivation on the farms we visited, the love of Japanese farmers for tillage became apparent. All farmers we met owned 3-point rototillers, and often these were their only tillage tools. The preparation of the soil involved repeated tillings.

For example, Hikaru-san told us about a weed management technique for rice where he floods his paddy, tills the sodden soil several times in order to separate out the weed seeds from the soil, and when the viable weed seeds float to the surface of the water, he drains the water off, removing the floating weed seeds with it. Do you see what I am saying about the level of tillage, and even wet tillage, that these farmers are accustomed to? It appears to reflect a totally different understanding of soil health.

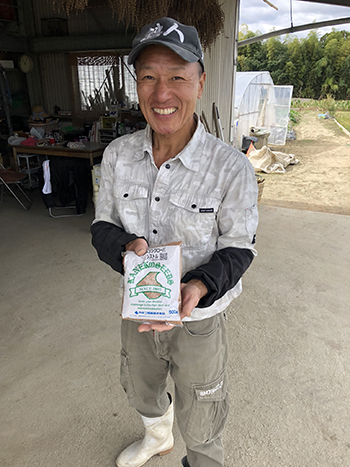

The farmer at Himarian was passionate about his white clover seed as a source of fertility - Grow your dreams.

Farmer Hikaru had to get back to the packing shed and his crew. We said goodbye and soon continued our journey southward on the bullet train. Next stop was Osaka, where we attended a Halloween party with a friend, where it turned out our American dance moves were VERY well-received by the partygoers.

Outside of Osaka we visited Himarian Farm. Our farmer-host worked an office job and farmed his fields on nights and weekends with his family. On this farm the weight of history was evident. This man’s family had farmed these 3 acres for 250 years; some of the hand tools he used had been used by his grandfather. You can imagine that it would be distressing to be the generation to stop farming, no matter what hardship you meet.

Himarian had a shed where machinery was stored and produce processed, a greenhouse, a composting area, and fields bordered by narrow irrigation ditches. As was common on the farms we visited, the machinery consisted of a smaller tractor (~30hp) with a rototiller, and this farmer also had a fertilizer spreader on the front of the tractor. Vegetables were grown in raised beds, with irrigation from the ditches bordering every field, though rain was ample.

Fertility was brought to a high art on many of these farms. The farmer at Himarian had a serious regimen. When we visited, the rice fields had been recently harvested, and the farmer was making bio-char from the piles of rice hulls leftover in the fields (see photo). As far as we could make out through translation, this farmer combined his bio-char with many other materials to make an ultimate fertilizer.

Rice hull bio-char was mixed with the rice bran, farm-made vermicompost, fermented soybeans (which are also eaten as a food called ‘natto’), and yogurt bacteria. Throughout our trip we saw that the organic farmers appeared to have a conception of soil fertility that focused on fermentation processes in the soil, making nutrients available to plants — very interesting.

The farmer at Himarian was passionate about his land and about organic farming and natural fertility. He told us: “Many Americans don’t understand organic, so they don’t understand what love is.” I can’t say I know exactly what that means, but I have thought about it a lot since meeting him. We would soon meet another farmer who would give us lots more to think about. Stay tuned for next month’s GFM for the second half of the journey.

Sam Oschwald Tilton helps farmers improve their weed management and machinery systems, and works with technical support groups to develop educational resources for organic agriculture through his business Glacial Drift Enterprises. He also organizes the Midwest Mechanical Weed Control Field Day (September 11th this year in West Lafayette, IN). Sam lives in Minneapolis and enjoys gardening with the neighborhood. If you want to talk to Sam about Japanese agriculture or anything else please email him - [email protected].

Paul Huber is the Farm Director at Troy Farm in Madison, Wisconsin, where he trains new farmers and grows food for the surrounding community.