This excerpt from the new book, The Winter Market Gardener, is reproduced with permission of New Society Publishers. All subscribers can get 20% off The Winter Market Gardener and all the books sold at growingformarket.com.

While the cold is certainly one factor limiting winter growing, it is not the only one nor is it the hardest to work around. For vegetable growers operating in a northern climate, one of the biggest hurdles to overcome is, in fact, the decrease in daylight hours and solar energy experienced in November, December, and January. For a successful winter vegetable production, anyone embarking on this adventure needs to understand the ins and outs of the season, and work differently than in summer.

The Winter Market Gardener is available from Growing for Market. Susbscribers always get 20% off all books.

The Winter Market Gardener is available from Growing for Market. Susbscribers always get 20% off all books.

To develop that exceptional flavor and grow healthy winter crops, two essential steps are required: developing strong seedlings, then hardening off these young plants so they can with- stand winter conditions.

Planting dates: planning for diminishing day length

The biggest limiting factor for winter crops is a lack of light, and not a lack of heat. In the fall, plant growth gradually slows down in almost all crops. As soon as day length drops below ten hours, growth essentially grinds to a halt. And so, every year, we witness a race against the clock on all farms that have a winter vegetable production. To make sure that vegetables will be close to maturity before they shut down for winter, each farm has to determine the best time to pull out summer crops and plant winter crops. In this game, time is not on our side.

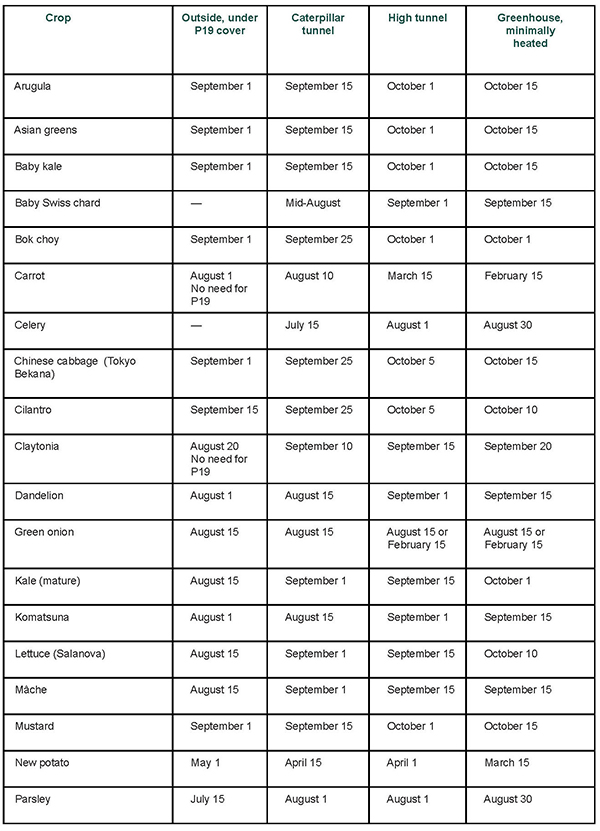

Winter planting dates for planting under row cover, caterpillar tunnels, high tunnels and minimally heated greenhouses in Hemmingford, Quebec, Canada. Though dates will vary in other locations, this gives an idea of how plantings can be staggered from earliest (under row cover) to latest (minimally heated greenhouse), and provide the basis for a planting schedule in other areas when adjusted for local conditions. All images are from the book The Winter Market Gardener and provided by New Society Publishers.

We must find a balance between getting those last harvests out of summer plants while still preparing winter crops. For abundant winter harvests, plants need to have reached at least 70 percent of their growth before day length drops below ten hours. At Ferme des Quatre-Temps, in Hemmingford, this critical moment arrives around November 1. After that, plants can still be harvested, though they will grow extremely slowly, if at all. The greenhouse or high tunnel then becomes a big cold room from which we draw fresh vegetables.

Starting in February, the days lengthen significantly. From then on, plants emerge from a winter sleep and start to grow vigorously again, in shelters protecting them from the drying effect of cold winds.

Several resources are available to determine the dates when day length is less than ten hours, according to your location. With this date in mind, you can use the days to maturity (DTM) for each crop to count backwards and decide when they should be planted in a shelter. It’s essential to add a few days to this date, to account for the diminishing sunlight and cold temperatures, which both slow down growth as autumn turns into winter. As a result of these conditions, the DTM for winter vegetables are not the same as their summer DTMs. From season to season, note-taking on planting and harvest dates will allow you to adjust DTMs for each of your winter crops.

Adjusting planting dates for a continuous harvest

For many vegetables that are harvested only once, determining the right planting date is relatively simple. You need to make sure that the plant will have almost reached maturity before day length drops to ten hours or less. However, this is not the case for vegetables that will be harvested multiple times over the winter (known as cut-and-come-again crops), like Salanova lettuce, arugula, and Asian greens. In a winter context, where growth comes to a near standstill, we can only get three cuts out of such crops over the entire season.

To secure a constant supply of these vegetables, you must adapt your seeding strategy according to the space available in your shelters. The goal is to have two or three different planting dates for these crops, allowing seven to ten days between seeding each succession. For us, this method increases the odds of successfully growing a continuous harvest and improves the predictability of our vegetable offering.

To choose planting dates for greens like tatsoi, arugula, mustard, and all the other components of our winter mesclun, we consider the fact that their leaves must be harvested when they are no bigger than the palm of a hand. This size is what makes a mesclun, and it is the most important factor in determining their maturity.

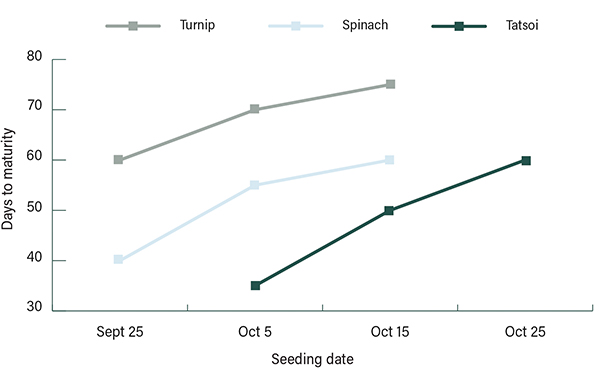

In summer, greens take ±30 days to reach the size we need. Based on our experience, tatsoi seeded on October 5 will mature in roughly 35 days, which is about the time required in summer. However, for a second succession seeded on October 15, tatsoi DTMs jump to at least 50 days. When the planting dates are delayed in the fall, we’ve observed a clear trend, with a drastic increase in DTMs as the pivotal November 1 date approaches.

This means that the longer we wait to seed a crop in October, the more its DTMs will be. When making a winter crop plan, you must take this reality into account. The graph on page 27 illustrates this increase in DTMs seen in the fall. After a first winter of experiments, you should be able to draw a similar graph for all your crops. This tool will be essential for planning your next winter season.

By now, you’ve probably realized that there really is an art to determining the right planting dates so that crops will overlap smoothly, providing an appealing and continuous vegetable offering throughout winter. At Ferme des Quatre-Temps, we are fortunate to have access to several shelters, so space is not a limiting factor. We make sure to plant our winter crops in shelters as soon as a spot is freed up by a summer crop. The planting date is therefore well before that pivotal moment when day length dips below ten hours. This ensures a smooth transition from one crop to the next, mitigating the effects of diminishing sunlight over the days leading up to the winter solstice.

Adjusting planting dates is a process of continuous improvement, year after year. Unfortunately, there is no magic formula that can be applied to all farms. Experimentation and rigorous note-taking are the keys to determining what works best in your context. You can also follow the schedule of another well-established northern farm and make changes along the way. This is how we started our experiments at Ferme des Quatre-Temps. As an example, here is a table of our own dates for fall and winter plantings. Of course, these dates are for a farm in southern Quebec, but they can still serve as a guide.

Decreasing crop density

Once our planting dates are chosen, there are a host of other factors to consider to create optimal conditions that will allow plants to reach maturity. Crop spacing is one variable that can be adjusted to compensate for decreasing sunlight. By increasing both the distance between rows and the number of plants per row, we ensure better light penetration and airflow. According to the biointensive model that we follow on our farm, crops are usually planted much more densely than on mechanized farms. One of the benefits of density is that crop foliage grows close together, obstructing the light supply that would otherwise go to weeds. This allows us to generate better yields per square meter than the standard yields on mechanized farms.

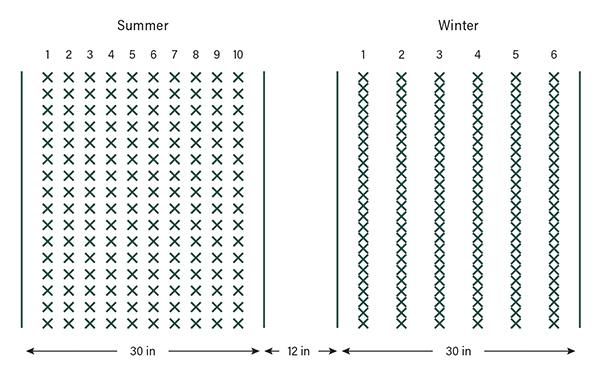

Figure 2: Changing crop spacing in winter increases access to light.

Figure 2: Changing crop spacing in winter increases access to light.

But in winter, as sunlight decreases, it’s important that all the leaves of each plant still have access to optimal sunlight so they can photosynthesize, which is essential for strong development. This requires some adjustment; for instance, most of our crops that are seeded at ten rows per bed in summer drop down to six rows in winter.

For salad greens, radishes, and turnips, we decrease the number of rows in the bed and increase their density within the row. In our experience, the best practice is to sow six rows at about 70 percent of the seeding rate assigned to ten-row summer seedings. For example, in summer we sow a total of 3.4 ounces (95 g) of arugula seed in a ten-row bed. In winter, we reduce the quantity and sow about 2.5 ounces (70 g, or 3.4 oz. × 70%) on a six-row bed. For more information, see Appendix 1: Winter Crop Spacing (p. 236 of the book).

Preparing plants for winter

For a successful winter production, another important factor is the need to acclimatize plants to the cold. As explained earlier, plants concentrate sugar in their cells in winter to protect themselves from the effects of low temperatures. To effectively set in motion this defense mechanism, it’s crucial that they be prepared (hardened off) well before and after planting, and to provide gradual exposure to the cold. When these steps are taken, many crops will become very frost resistant. We have stopped counting the number of times we’ve stepped into an unheated greenhouse on a winter morning and opened a row cover to reveal a bed of fully frozen vegetables after a very cold night. For a vegetable grower who has little experience in winter farming, this can be shocking—it’s a complete loss! But as the morning goes on, the sun’s energy slowly warms the greenhouse, and a miracle occurs: the plants thaw and become as beautiful and alive as the day before. Witnessing this metamorphosis is extraordinary, but it is also a daily occurrence on a farm with crops that have been hardened off.

Several crops or varieties naturally cope well with the cold. Some can even be quite resilient when faced with a short-lived hard freeze. But these same crops will suffer permanent damage and even die if below-freezing temperatures persist. This is the case for arugula leaves that can endure temperatures as low as 18°F (–8°C) for less than two hours but will suffer permanent damage if exposed to 25°F (–4°C) for more than twenty-four hours. Arugula, like all cold-hardy crops, has an energy reserve that will bring it back to life as soon as the sun warms the greenhouse. That said, plants will more effectively recover from temperature variations that are typical of winter growing if they have been hardened off well before freezing temperatures strike. To achieve adequate cold tolerance, we recommend following two guiding principles.

Principle no. 1: develop a strong root system

In order to withstand temperature changes, winter crops must have well-established root systems. To make sure our plants develop strong root systems well before temperatures drop below freezing, we need to act fast. Once summer crops are removed from shelters, winter crops are quickly transplanted or seeded into that same space, to take advantage of the favorable fall weather. Most of these have been growing in our nursery to get a head start of a few weeks. The longer plants can benefit from mild temperatures and long daylight hours, the stronger their root systems will be. Important detail: when preparing our winter seedlings in the nursery, any crop that will eventually be transplanted is seeded into larger containers. So, for example, a vegetable that would be sown into a 128-cell tray in summer is instead seeded into a 72-cell tray for winter. This gives seedlings more space to develop a robust root system and allows us to give winter crops a head start while keeping summer crops in the greenhouse for one or two more weeks.

Principle no. 2: harden off gradually

To help plants withstand more severe frosts, it’s critical to harden them off in an intentional and gradual manner. We purposely expose crops to colder temperatures by leaving them without a row cover or by opening the greenhouse or tunnel to let the cold air in. This occurs around mid-November, when most of the planted crops are established and have almost reached maturity. We gradually increase their cold tolerance before temperatures begin to drop below freezing. Plants that have not been hardened off, in comparison, are more affected by below-freezing temperatures. Ice crystals form in their cells and tear through them, resulting in a dark green color and a wet appearance. The damage is irreversible, and the crop will unfortunately be lost.

To harden off plants, the trick is to ventilate the space as much as possible before temperatures drop below freezing. In November, when plants are well-established and temperatures stay above freezing, we keep our greenhouses and tunnels open, to gradually expose our crops to colder temperatures.

To harden off plants, the trick is to ventilate the space as much as possible before temperatures drop below freezing. In November, when plants are well-established and temperatures stay above freezing, we keep our greenhouses and tunnels open, to gradually expose our crops to colder temperatures.

Crops sown later in the season (after September 30) have this advantage: long after Christmas, once the sunlight begins to increase in February, they can provide excellent harvests.

If you have enough space in your shelters, the best strategy is to sow winter crops every week from the beginning or middle of September until the end of October. This approach will result in good harvests before Christmas and in the spring, until summer crops are planted in the greenhouse.

The dates suggested in figure 1 represent our tests, run in Hemmingford. What works elsewhere depends on specific climate and—most importantly—latitude, which determines the amount of sunlight available for growing vegetables. The proposed planting dates represent what is realistic, while still considering the end of summer crops (tomato, eggplant, cucumber). It may be possible to plant winter crops earlier on your own farm.

Figure 1: Days to maturity increase as sunlight diminishes.

Figure 1: Days to maturity increase as sunlight diminishes.

This excerpt from the new book, The Winter Market Gardener, is reproduced with permission of New Society Publishers. All subscribers can get 20% off The Winter Market Gardener and all the books sold at growingformarket.com.

Jean-Martin Fortier is a farmer, educator, and advocate for regenerative agriculture. He is author of the international bestseller The Market Gardener, founder of Growers & Co., and co-founder of the Market Gardener Institute. In 2015 he established the research farm la Ferme des Quatre-Temps. He lives and farms in Quebec, Canada.

Catherine Sylvestre is a professional agronomist and director of vegetable production and leader of the market garden team at la Ferme des Quatre-Temps. She develops, implements, and teaches best practices for cold season growing, specializing in crop protection and greenhouse production for northern climates. She lives in Quebec, Canada. For more on winter growing, listen to the interview with co-author Catherine Sylvestre on the Growing for Market Podcast!