Damping-off, algae, fungus gnats, ammonia and more

By Caleb P. Goossen, Ph.D., Crop Specialist for the Maine Organic Farmers and Gardeners Association

Early spring is a time when many farmers are starting seedlings in heated greenhouses and grow rooms. While these are much more controlled settings than outdoor fields, problems can still arise, and farmers should be on the lookout for indications that plants may be stressed. Both biotic (i.e., living) and abiotic (i.e., non-living) issues can arise. It’s important to understand the difference, and how to prevent and treat symptoms as they emerge. Abiotic problems are not infectious, and are sometimes transient (e.g., cold temperatures or cloudy weather).

Before starting seedlings, determine which growing medium will work best for your needs. Do you need a potting mix that will stick together well in soil blocks, a lightweight mix for seedlings that will be planted out or potted up in short order, or a more nutrient-dense compost-based mix for crops that will be in their containers for a long time? Biotic and abiotic problems can result from potting mixes carrying plant pathogens or insufficient nutrients.

A seedling showing the classic signs of damping-off- a pinched stem at soil level causing the seedling to keel over and die. Photo by Eric Sideman.

In compost-based potting mixes, nutrient availability also depends on biological activity, which is greatly affected by temperature, moisture content, and oxygen availability. Many commercially available organic mixes are consistently free of pathogens and also have the appropriate nutrient ratios but occasionally even these fail, so it’s important to know your source well.

Once your crops emerge, it’s good practice to regularly check new growth to see how it looks relative to any symptoms elsewhere on the same plant, and to check on the health of the roots and crown of the plant. Some of the problems you may encounter in your propagation are described below and should help you know what to look for when scouting each day.

Damping-off

Damping-off is a biotic disease most often seen in young seedlings, though it can (rarely) affect older plants. It is caused by several species of fungi and fungi-like organisms that commonly live in soil and jump at the opportunity to infect germinating seeds and seedlings when conditions allow them to. The most common species that cause damping-off are in the genera Pythium and Rhizoctonia.

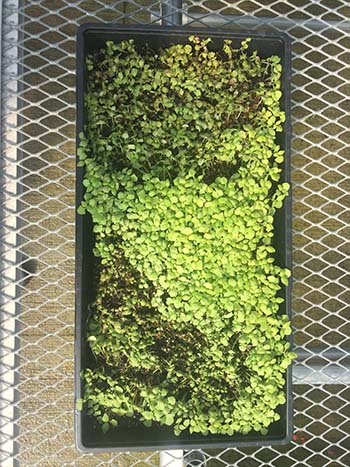

The dying seedlings in the top and bottom of this tray are caused by damping-off, made worse by the fact that this tray was planted too densely, hindering airflow. Photo by Andrew Mefferd.

There are two presentations of this disease. The first is pre-emergence damping-off, which rots the sprouting seed before it breaks through the soil. This is often confused with poor seed germination. The fungus can attack any part of the germinating seed, especially the tiny growing tips. The second is post-emergence damping-off, which begins as a lesion on the root that extends up the stem and/or above the soil line. The young stem is constricted by the attack and becomes soft, leading to the plant falling over and dying.

Management for damping-off

Damping-off cannot be cured, but it can be prevented by starting seeds in better conditions (or a “sterile” potting media). First make sure you are using seeds of the highest quality that will germinate and start growing quickly. Old, mistreated, and weak seeds are more susceptible to damping-off, as anything that slows germination increases the risk of infection.

Excessive watering, poor drainage, and “less than optimum” temperatures should also be avoided. Allowing the surface of the soil mix to dry a bit before each watering helps, so long as the seed is large enough to have been planted below the surface (e.g., tomatoes, eggplant, squash, etc.). Additionally, adding perlite to your potting mix can help to facilitate soil drying and aeration.

You can see how these basil seedlings infected by Rhizoctonia solani are suffering from damping-off and rotting from the ground up, causing them to fall over and eventually die.

While not possible on a large scale, it is possible to “sterilize” a compost-based potting mix by baking it in the oven at 350 Fahrenheit for about 45 minutes. The mix should reach 160 Fahrenheit and should stay at that temperature for 30 minutes. Do not allow it to go higher or stay hot longer because overheating kills more of the beneficial microorganisms and may release toxic materials.

Many growers prefer not to “sterilize” their mixes because organic mixes are living systems and often the interactions of beneficial organisms in the mix reduce the impact of the fungi causing damping-off. In other words, if the damping-off pathogens get into a “sterile” mix, they are able to establish more easily in the absence of competition. A more accessible and biologically supportive alternative is to add a biological treatment to your potting mix; for example, a product like RootShield may help to inoculate your seedlings with beneficial microbes that will antagonize or compete with damping-off microbes.

Cold/wet soil

In addition to encouraging damping-off, cold soil can cause other problems. Growing seedlings in improperly heated spaces is often problematic due to cold nighttime temperatures. The roots of most crop plants do not function well when cold, and plants frequently display symptoms of malnutrition even though the media may have plenty of nutrients. Purple undersides of leaves, stunted growth, and pale weak seedlings are often the results of cold or wet “feet.”

In this closeup from the previous image, you can see how the rot is traveling up the stem. Both images by Gerhard Bedlan, licensed under CC 4.0.

Seedling roots can also be shocked by cold water. Water coming from drilled well sources is often at a low temperature in the early greenhouse season. Any effort to temper cold irrigation water can be helpful. For a larger operation, that might look like a purpose-built water heater/temperer. In a smaller operation, one may simply increase the length of the hose holding water in a warm area and carefully time water usage to allow the replacement well water to warm up in the hose before use.

Wet potting mix, or potting mix that doesn’t get a chance to dry out on the surface, can also foster algae growth. While algae are harmless to plants, algae can form crusts on seedling cells that make even watering and drying more difficult, or possibly slow air diffusion in and out of the potting media, which can hinder root growth and further exacerbate wet potting mix problems. Algae may also foster fungus gnats, which make seedlings less attractive to potential customers, and feed on algae and fungus in damp potting media and sometimes on your tender seedlings’ roots, too.

Management for cold/wet soil

Trying to grow a tiny seedling in a large container worsens the problem of wet potting mix because the plant is just not big enough to move much water, and overwatering may become a problem the plant cannot grow out of. Perlite can help to improve drainage in a poorly-draining potting mix.

Rhizoctonia solani symptoms, including brown roots and stem lesions, on bean plants. Image by Howard F. Schwartz, Colorado State University, licensed under CC 3.0

Rhizoctonia solani symptoms, including brown roots and stem lesions, on bean plants. Image by Howard F. Schwartz, Colorado State University, licensed under CC 3.0

The first step in responding to fungus gnats is cultural — reduce the amount of time your potting mix has surface moisture. In severe infestations, there is an OMRI-approved Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt) product (Gnatrol, a formulation of the israelensis strain of Bt) that works well. Repeated applications of predatory nematodes can also be effective in killing larval and pupal stages of the gnats.

Compost for potting mix

To prevent issues with your growing medium, it is advisable to get an analysis of any compost you plan to use if you’re building your own potting mix. There are soil health testing labs in every state throughout the country. Wherever you get your soil tested, be sure to ask for the compost analysis when you send a sample. If you are buying a commercial compost-based mix, you may want to speak to other growers in your area and ask how that brand has worked for them.

Salt

Some composts are high in soluble salts. Even if the salts are nutrient salts, high levels can cause water absorption problems and may prevent seeds from germinating. The final blend of a compost-based potting mix (or any other mix) should not have salts — measured as electrical conductivity on a compost analysis — higher than 4 millimhos per centimeter (mmho/cm).

Carbon to nitrogen ratio

The carbon to nitrogen (C:N) ratio is critical for compost used in potting mixes. A high C:N ratio will result in nitrogen lock-up, wherein all the nitrogen in the potting mix, and any you add with fertilizers, is being grabbed by the bacteria feeding on the carbon-rich material. It is a sign that the compost was made from an improper mix of feedstock or perhaps is just not finished yet. Compost used to make potting mixes should have a C:N ratio of 15:1 to 18:1.

Ammonia

As nitrogen is released from decomposing proteins, it passes through a phase where it is an ammonium ion. Unfinished compost will have ammonium ions that may revert to ammonia gas, which can kill roots and damage leaves. Ammonia should be less than 0.1% in compost used for potting soil. Plants suffering from high ammonia levels will look weak and have brown roots instead of healthy white roots.

Setting yourself up with a high-quality growing medium, proper systems in your propagation space that help to regulate temperature and airflow, and properly managing irrigation will all help to ensure you have favorable conditions for seedlings. With daily scouting, you can catch issues that arise before they become major problems.

Please note: This information is for educational purposes. Any reference to commercial products or trade or brand names is for information only and no endorsement or approval is intended. Pesticide registration status, approval for use in organic production, and other aspects of labeling may change after the date of this writing. It is always best practice to check on a pesticide’s registration status with your state’s board of pesticide control, and for certified organic commercial producers to update their certification specialist if they are planning to use a material that is not already listed on their organic system plan. The use of any pesticide material, even those approved for use in organic production, carries risk — be sure to read the label and follow all instructions. The label is the law. Pesticides labeled for home garden use are often not allowed for use in commercial production unless stated as such on the label.

Caleb Goossen is the organic crop specialist of the Maine Organic Farmers and Gardeners Association (MOFGA) and the author of MOFGA’s Pest Report newsletter (sign up at mofga.org/newletter-sign-up-pest-report). Formed in 1971, MOFGA is the oldest and largest state organic organization in the country. MOFGA’s mission is to transform the food system by supporting farmers, empowering people to feed their communities, and advocating for an organic future. Learn more at mofga.org.