Over the last two years, our farm has been increasingly hiring foreign-born workers from immigrant, refugee, and migrant communities. The result has been the best team we’ve ever had, and a new meaning for our farm which has grown into a community where people from all over the world can find reliable, rewarding, and safe employment.

When we first started hiring, around six years ago, we asked farmer friends where they found employees and got some common answers. Farm-focused websites like ATTRA and Good Food Jobs were common for recruiting, as were local colleges, and many farmers advertise job openings to their local customer base.

Many refugees have skilled backgrounds in agriculture or professional experience in related fields like construction, carpentry or electrical work.

Following friends’ advice, we found our first employees via these routes and found we had a pretty homogeneous applicant pool. Many applicants for our farm jobs were American-born, in their 20s, and came from relatively affluent backgrounds. They generally were college educated with relevant degrees like ecology or sustainability. Many had worked briefly on small farms (often non-profits), and resoundingly they expressed a dream to own their own farms someday.

All of this sounded great on paper, but in practice these candidates often didn’t work out. What our young farm needed was strong bodies–people able to weed all day, haul buckets around, and harvest flowers at a rapid pace. Recent college grads eager to learn more about ecology found the farm work boring and difficult. They weren’t very financially motivated and would often take a lot of time off.

As a new farm, we didn’t have grander work or major career advancement to offer. As employee productivity waned, we found we could often work four or five times as fast as our staff. Resentment grew and our earliest employees didn’t last more than a season (some a lot less). After they left our farm, none of those workers went on to other farm jobs–most ended up in office jobs. Farm work isn’t for everyone, and they learned that working here.

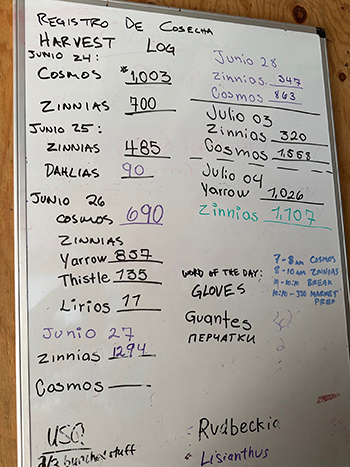

We’ve all been learning each other’s languages and started posting a “Word of the Day” in all three languages now spoken at the farm.

Then one day a guy named Yurii showed up at our farm gate. He didn’t speak any English but was eager to work and we decided to give him a shot.

Yurii had been a park ranger in Ukraine, where he worked outdoors and helped tend horses in a Ukrainian national park. He was used to outdoor manual labor in all weather conditions and quickly jumped in on all farm tasks working more efficiently and more cheerfully than any employee we had ever hired.

Despite the language barrier, Yurii rapidly learned the different flower varieties, how to set up irrigation systems, and the various planting requirements of dozens of species. Three years later, he’s our longest lasting employee, an expert in cut flower cultivation, and a vital part of our small team. We began to ask ourselves: Where can we find more Yuriis?

Connecting with local refugees

Early last year, we connected with a local refugee resettlement agency looking to place recently settled refugees into jobs. Similar agencies are found across the country, especially in the suburbs of larger cities. Many are connected to an international humanitarian organization called World Relief, through which you can find other local organizations. The future of refugee resettlement is currently in question in the United States under the new administration, but many refugees are still actively looking for employment.

Many refugees have backgrounds and experience useful to farms. Unlike in the United States, where only around 2% of people work on farms, many people in South American countries grow up doing farm work. In Guatemala, for example, nearly a third of people work on farms. Through the refugee organization, we initially hired two and then eventually three workers.

All of them had some farming experience plus additional farm-adjacent skills. One was an electrical engineer; another had worked as a professional driver; and one even had a degree in agronomy. But above all, they were all happy to do tough physical labor and excited by the opportunity for reliable, safe employment.

Sometimes the language barrier is actually a help, as instructions must be clear and concise.

The majority of refugees here on humanitarian visas have work authorization and have undergone extensive background checks. Many recent refugees are joining family and friends in the community. The Uniting for Ukraine program, for example, which brought thousands of Ukrainian refugees to America, required sponsorship from a local family member or friend.

Humanitarian organizations also help new immigrants get settled in the country. Our workers found housing through these organizations, and were also driven to work for the first few weeks by volunteers. Because of this strong support network, they were similar to American-born workers we had previously hired–just a lot more hardworking.

Exploring H-2A migrant workers

Around the same time we were welcoming refugees to our farm, we also brought on our first H-2A visa workers. Unlike immigrants, who have moved to the U.S. permanently, H-2A workers are seasonal employees. They can stay in the country for up to 3 years but can only work on an individual farm for up to 10 months at a time. Last year, we brought two H-2A workers here from Guatemala for seven months (June-December). This year we expanded to three H-2A workers for the full ten months (February-December).

Celebrating the 4th of July as a team with my family’s traditional pie. All photos courtesy of the author.

Every farmer I’ve spoken to about the H-2A program has had an overwhelmingly positive experience, and ours has been the same. The three workers we’ve brought here from Guatemala all have farming experience and are incredibly hard workers. While our year-round immigrant employees have U.S.-based families and lives they are building outside of work, our H-2A workers are here for one reason: to work. They’re eager for as many hours of work as possible, and they send a large portion of their paychecks back to Guatemala, where their families still live.

While our farm grows year-round, we have significantly more flowers during the high season from spring to fall. The mix of year-round employees plus H-2A workers for our busier season is working out well.

Unlike the immigrant workers with strong local support networks, our H-2A workers are extremely reliant on us for many of their living needs.

The biggest one is housing. To participate in the H-2A program, we must provide housing to our workers. We rent a house for them nearby, which makes us their de facto landlords. We supply everything from toilet paper to heating oil and furniture and conduct a weekly housing check to make sure everything is in working order.

We also must provide our H-2A workers with transportation to and from work, and to the grocery store at least once a week. This is another DOL requirement.

We’ve found that there are many additional responsibilities for our H-2A workers above and beyond the basic DOL requirements. For example, we wanted to help them get health insurance in case they became ill or had a major accident while in the country. To qualify, they needed to get Social Security Numbers, and we had to help guide them through that process. We’ve helped them with tasks like banking and sending money, filing taxes, and accompanying them to doctors’ appointments and clothing stores.

Ultimately, the relationship we have with our H-2A workers is much more intimate than those we’ve had with our immigrant or American-born employees. They’ve become like family.

For farmers who can afford housing but only have seasonal employment to offer, the H-2A route is a great choice. But for farmers who can offer year-round employment and don’t want the complexities of the visa process, refugees are excellent workers with less administrative headache.

Legal considerations

All of the workers hired on our farm have legal work authorization, but in today’s climate around immigration, it’s important to keep good records and ensure foreign-born workers are aware of their rights. We have all workers complete a form I-9 for Employment Eligibility Verification on their first day of employment and provide proper identification with the form. We also take photocopies of these documents for safekeeping. I-9s are required to be retained for three years after the date of hire, or one year after employment ends, whichever is later. Sometimes, for example if a work authorization card expires, we’ll have workers complete updated I-9s to ensure we have all of the necessary paperwork in place.

We regularly discuss with staff what to do in case of an immigration raid. All of our workers have a copy of the Immigrant Legal Resource Center (ILRC) Red Card, a printable wallet-sized document summarizing what to do in case of an immigration raid. We also have posters from the ACLU in our barn reminding workers of their rights. Workers with limited English proficiency are vulnerable to confusion when faced with questioning by law enforcement. Finally, we have an immigration attorney on call in case any legal-related issues do arise.

Transportation

Reliable transportation can be a critical issue for both migrant and refugee employees. Many of our refugee workers also did not initially have driver’s licenses or cars, and they relied on volunteers or expensive taxis to get them to work each day. Similarly, H-2A workers require daily transportation to work as well as regular trips to town for shopping. Initially, we did this driving ourselves, but it became a burdensome extra task in addition to running a busy farm.

We solved this problem by helping two of our immigrant workers get driver’s licenses. We hired a Spanish-speaking driving instructor nearby, who helped them pass road tests for US driver’s licenses. We then bought an inexpensive used minivan for the team. Each morning, one of our employees clocks in remotely via an app and then picks up the entire team (both H-2A and immigrant workers) from their homes. This has also solved employee tardiness issues we used to have. The entire team arrives together right at 7 a.m., ready to work. We pay for minivan maintenance and gasoline, so the transportation works out as a great benefit for our workers as well.

Cultural and language considerations

Language can be a barrier for many immigrants and H-2A workers. While Spanish and other major languages are frequently spoken, some workers may only know less common and indigenous languages which may not be readily accessible in translation services. The majority of our staff speak Spanish, and we have one Russian speaker, which means that Google Translate can be used effectively for our daily conversations.

Many of our workers are away from their homes and families, so we take extra care to celebrate birthdays and other life events at the farm.

Ironically, the language barrier has actually improved communication on our farm. When giving instructions to native English speakers, we would frequently give information quickly and in passing, leading to miscommunication and mistakes. When working with translation, we have to take extra care to use clear and precise language. We also more frequently put instructions in writing, and are more careful to double check that instructions are understood. As a consequence, we find that projects are more often completed correctly on the first try than they used to be with our all-American staff.

Language also provides an opportunity to show mutual respect and forge connections. Our staff has been learning English and we’ve been working to learn their languages, especially Spanish since it’s the most commonly spoken language on our farm. Sharing vocabulary daily and helping teach pronunciation have made us better communicators and better friends.

Cultural differences can span beyond language. Coming from homes from all over the world, workers may have different expectations for how to interact with their coworkers. As part of a grant program called the Farm Labor Stabilization and Protection Pilot Program, we hosted a worker rights training by an organization called Alianza, which has materials available online. Their training covered topics like sexual harassment and mutual respect, good topics to cover in employee handbooks, to ensure that everyone understands the rules on the farm.

Making the farm feel like home

Because many of our immigrant and guest workers are away from their homes and families, the farm has taken on a new importance and coworkers have become close friends. We’re learning that recognizing birthdays is more important than ever before, so we’re always careful to get cakes and celebrate with our workers. We also find new ways to share each other’s holidays and traditions. On my birthday, our workers brought in festive tamales for us all to share. On the 4th of July, we made an American flag pie and had a party.

With a reliable workforce, our farm has been able to grow and sell more flowers than ever before.

This year we’re also planting a shared crew vegetable garden. We gave our staff seed catalogues so that they could pick out special varieties important in their traditional cuisines. We have lots of beets planned for Ukrainian salads and plenty of chili peppers for Guatemalan salsas. Along with food, sports can also be a fun and easy way to bridge cultural divide – having a soccer ball to kick around the farm and learning each other’s sports teams can make for a friendlier environment.

Ultimately, hiring this diverse staff has changed our farm in wonderful ways. The weeds are more contained than ever, harvesting and planting is completed much more efficiently, and we have a better bottom line. But maybe more importantly, the farm has a new sense of purpose. With around a dozen children around the world now supported by parents’ paychecks from our farm, our success feels more meaningful.

Rebecca Kutzer-Rice owns Moonshot Farm, a specialty cut flower farm in East Windsor, NJ. She grows flowers year-round including in a geothermal greenhouse, for retail markets in and around NYC.