This article is in the September 2021 issue of Growing for Market Magazine.

Last September 7th, my husband and I stayed up late after our children fell asleep in makeshift beds in our downstairs living room. We told them we’d all sleep there to enjoy being together during a late summer wind storm; actually, we wanted all of us to be closer to exits in case we had to evacuate quickly. Our power had gone out early in the evening due to the wind we could hear blowing all around our house.

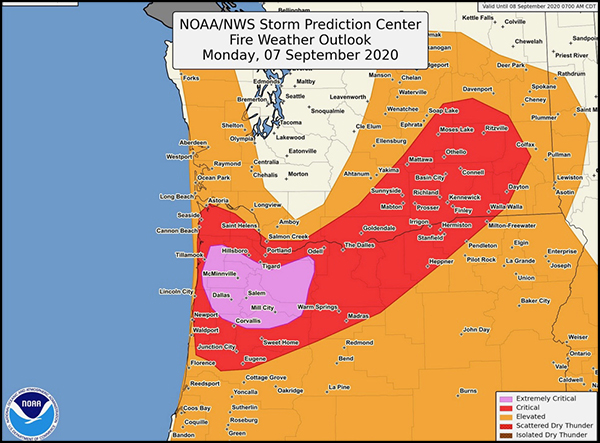

The air was already thick with smoke from fires to the northeast. The combination of high temperatures and sustained winds were creating a “red flag warning,” or extremely high risk of wildfires. On an online weather map, a circle of pink ringed our farm Oakhill Organics in Yamhill County, Oregon, marking us at the very center of “extremely critical” fire risk, which is the highest risk level.

While my husband Casey gathered our computers, food, documents, and other essentials in bags by the door, I stayed glued to my phone, watching in terror as wildfires began to be reported across our county. Just a few years earlier a fallen power line had ignited a grass fire in the field directly upwind from our house, and now we pictured how quickly a blaze could move through the dry vegetation should a similar scenario happen in those “red flag” conditions. We hardly slept that night.

The author’s farm is located in the very center of the pink “extremely critical” NOAA fire risk map from last September. All images courtesy of the author.

The author’s farm is located in the very center of the pink “extremely critical” NOAA fire risk map from last September. All images courtesy of the author.

The following days brought growing fires, more smoke, record-high air pollution, dark skies, evacuations, and the destruction of thousands of homes here in Oregon and across the West. We harvested vegetables for our CSA that week while wearing KN95 masks and washed the fallen ash off our produce as best we could. We watched as our important fall crops stalled in their growth as the skies stayed dark red and surreal premature winter light levels set in during what should have been the critical final weeks of our growing season.

Pacific Northwest climate change

While this scene felt like something out of a movie, it was real — and, unfortunately, it is becoming all too familiar for farmers and residents of the Pacific Northwest, as climate change brings more heat, severe droughts, and increased wildfires to our region.

The Pacific Northwest comprises the western half of Oregon, Washington, and British Columbia. This is a geographically diverse landscape, shaped by volcanic mountain ranges and fertile, sprawling river valleys. The nearby Pacific Ocean moderates temperatures, creating a temperate region with a long growing season ideal for growing a wide range of crops. Farmers produce everything from fresh market vegetables, wine grapes, hay and climate-sensitive nursery and seed crops. The good growing conditions, abundant farmland, and favorable food culture in metro areas have fostered a booming economy of market growers — all of whom now must face the new realities of climate change.

Map with the locations of the farms interviewed for this story.

Map with the locations of the farms interviewed for this story.

According to Oregon State University’s Climate Impacts Research Consortium, the Pacific Northwest has warmed by about 1.3° F (0.7 C) since the beginning of the 20th century. The region is expected to continue to warm through this century and by 2100 becoming 2 to 15° F (1 to 8 C) warmer than the second half of the 20th century.

Precipitation is expected to shift more to the winter months, mostly in the form of rain. This will lead to longer seasonal droughts and less snowpack. Reduced snowpack is likely to decrease the amount of water available through the growing season for farmers, municipalities, and wildlife.

Farmers I spoke with in our region are already very conscious of the changes and making plans for the potential increased severity of the climate changes going forward. While the heat, drought, and wildfires are all very interconnected, they each bring their own challenges and possible solutions, so for the purpose of this article I will address these as three separate elements of one big set of challenging changes.

On the morning after the terrifying September night the author describes in this article, she watched as more smoke rolled up from fires burning at the western edge of Oregon’s Willamette Valley. The skies stayed smoky and the air hazardous for over a week.

On the morning after the terrifying September night the author describes in this article, she watched as more smoke rolled up from fires burning at the western edge of Oregon’s Willamette Valley. The skies stayed smoky and the air hazardous for over a week.

Heat is hard for humans and plants

In late June of this year, a heat wave broke all previous records here in the Pacific Northwest. Temperatures at our local weather station in McMinnville, Oregon, skyrocketed, reaching highs of 110° F (43 C) and then 115° F (46 C) on subsequent days. On June 29 the town of Lytton, British Columbia, set an all-time high record for Canada at 121° F (49.5 C). After the heat wave hundreds of heat-related deaths were reported across the region. The historically temperate Pacific Northwest is not familiar with nor prepared for such extreme temperatures.

While this recent heat event was extreme (and deadly), heat waves have become more common in recent years and are part of climate modeling for the future. Such high temperatures make working outside challenging. Anne Schwartz of Blue Heron Farm has been farming in Washington’s Eastern Skagit Valley for 42 years. She says that the increased heat has been hard on her and her crew: “I remember one particularly brutal summer four or five years ago, after weeks above 95° with lots of over 100° days, looking at the forecast and weeping.” She said that they can no longer work long days because the heat stress is so intense in the afternoons. Instead, they have shifted to early starts and working six shorter days a week.

Last September, wildfire smoke decreased light levels on the author’s farm so much that she and her husband observed critical fall crops that halted their growth completely for several weeks.

Last September, wildfire smoke decreased light levels on the author’s farm so much that she and her husband observed critical fall crops that halted their growth completely for several weeks.

Beth Satterwhite of Even Pull Farm in McMinnville, Oregon, reports that the heat is also hard on their plants. “The dramatic swings in weather are definitely causing additional stress in our crops: we’ve seen things bolting prematurely or generally just not looking stellar,” she said. The stress also seems to attract added pest pressure. Their farm addresses the stresses by growing a diverse range of crops. They have also built more high tunnels on their farm so that they can increase the amount of crops they grow year-round. Satterwhite’s goal is to have crops maturing in every season so that if a severe weather event hurts one season’s crops, they will still have other crops and other seasons coming.

Smoke from wildfires created red skies and hazardous air at the author’s farm for over a week last September.

Smoke from wildfires created red skies and hazardous air at the author’s farm for over a week last September.

Many farmers reported similar strategies, including continually trialing new varieties of vegetables because climate shifts are changing the environments on their farms. For example, a lettuce that might have worked 10 years ago now bolts earlier and needs to be updated with a more heat tolerant variety.

For some farmers at the mountainous edges of the Pacific Northwest, the increased temperatures have created a growing season where there wasn’t one before. Chris Lawrence has been farming in central Oregon for 40 years. He used to grow hay and was surprised when his daughter Sarahlee wanted to start growing vegetable crops, something he thought was impossible. “I had lost my garden three times around the 4th July due to a freeze,” he said. Now, they can grow reliably in the summer and have transformed their farm, Rainshadow Organics, into a diverse Full Diet-style farm with both produce and animal products.

Projected extreme weather events can come in many forms, including this February’s ice storm that caused record-breaking power outages and tree damage in Oregon’s Willamette Valley. Everything on the author’s farm was coated with thick ice, and they lost power for a week.

Projected extreme weather events can come in many forms, including this February’s ice storm that caused record-breaking power outages and tree damage in Oregon’s Willamette Valley. Everything on the author’s farm was coated with thick ice, and they lost power for a week.

More water needed, less available

Seasonal droughts have always been a part of the Pacific Northwest climate. Precipitation in most of the region is fairly moderate and falls primarily from October through April. Here on our farm we can expect to get an average of 43 inches of precipitation per year, most of it during those months.

From May through September — i.e., the main growing season — many Pacific Northwest farmers can expect almost no rainfall at all. That means that almost every commercial grower in the region owns and uses some form of irrigation as standard farm operations. Having reliable access to irrigation water is usually a critical element of farming here, whether it be from a well or a surface water source such as a pond or river.

So, to that end, some of the dry weather coming with climate change is not entirely new for farmers. However, the dry season has been extending. Combined with new high temperatures over the course of a season, local farmers are challenged.

On our farm, we have found ourselves needing to irrigate regularly from as early as late March until late October. This process creates expensive extra work for our farm, and even with diligent irrigation efforts, it can feel as though we are often barely keeping up with the needs of the plants.

In response to these longer droughts, some farmers in the region are experimenting with dry farming in certain seasons, while others are trialing new varieties of familiar vegetables to see which ones can withstand the new extremes of drought with some irrigation.

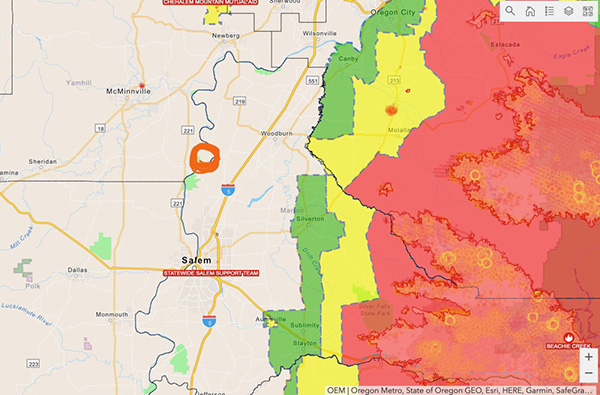

In this fire map from last September, the author’s farm is circled in orange. The fire boundaries themselves are outlined in dark red, while the red, yellow and green blocks represent various levels of evacuation orders. Many Willamette Valley farmers had to evacuate their farms during these final, important days of the main growing season.

In this fire map from last September, the author’s farm is circled in orange. The fire boundaries themselves are outlined in dark red, while the red, yellow and green blocks represent various levels of evacuation orders. Many Willamette Valley farmers had to evacuate their farms during these final, important days of the main growing season.

At the southern edge of the region in Williams, Oregon, Don Tipping has been growing vegetable seed for 25 years. He says that his company Siskiyou Seeds has incorporated more of what he calls the successful “Pacific Northwest dryland crop suite,” including fall planted garlic, onions, arugula, fava beans, mustard greens, poppies, kale, collards and leeks, among others. He’s trying to identify the crops that can grow with the fall and winter rainfall and then flower and dry down in spring for seed crops.

Many of these same crops would also perform well in similar conditions for market growers to harvest for early markets and CSA boxes. “Climate change provides many opportunities for plant breeding and selection,” Tipping noted, something Siskiyou Seeds and other Pacific Northwest seed growers are actively doing in attempts to stay ahead of the curve of the changes.

Many farmers are also working to make existing irrigation systems more water and labor efficient. Beth Hoinacki of Goodfoot Farm in Kings Valley, Oregon, said that they are working on developing irrigation systems that require much less labor because moving handline is expensive, and they are having to do more and more of it. This year as she plans irrigation for a new field, she is finding that supplies are running low at local farm suppliers as every farm is ramping up their irrigation efforts. She said the prices also seem to be fluctuating.

Being able to afford the irrigation supplies and labor is one challenge, but other farmers are finding themselves struggling with their water supply itself. In Washington, Anne of Blue Heron Farm says that in the hotter, drier recent years, they have actually pumped their well dry a few times. “We need to pay closer attention to limiting water use late in the season, and that was never an issue before.”

As climate models show more of our region’s annual rainfall shifting to winter months in the form of rain rather than mountain snowfall, less precipitation is stored in the snowpack. Some farmers are strategizing to mitigate that change. Siri Erickson-Brown of Local Roots Farm in Washington’s Snoqualmie Valley has joined the board of her local drainage and irrigation district. They are working to find new ways to store heavy winter rains to help with in-stream flow in the summer. She says they’re not developing “your typical main-stem dam projects,” but solutions “more like beaver-assisted (or beaver-imitating) impoundment for better groundwater infiltration and micro-storage, such as in decommissioned manure storage ponds.”

The ultimate danger: wildfires

Along with the rest of the world, here in the Pacific Northwest we face the increased frequency and variability of extreme weather events in general. That can include a range of events such as this February’s ice storm that caused record-setting power outages and tree damage in Oregon’s Willamette Valley. Yet, a primary concern is more “red flag warning” weather events, such as the one I described in the beginning of this article. These are weather systems that combine high temperatures, low humidity, and high winds, creating extreme risk levels for wildfires in dry landscapes.

During last September’s wildfire season, ash settled on the author’s farm, vegetables, and car windshield.

During last September’s wildfire season, ash settled on the author’s farm, vegetables, and car windshield.

Natural and human-controlled fire has long been a feature of the region, but past fire suppression, commercial monoculture forestry methods and human-caused sources of ignition have combined to create wildfires that are increasingly hard to contain in places where they encroach upon homes, businesses, and farms.

Last September, practically the entire West Coast was blanketed from smoke from fires burning in every state. Living with some level of air pollution from smoke has become an increasingly normal part of late summers in the Pacific Northwest, but on this occasion the fires themselves encroached into human population centers faster than ever, including places that historically had not been at risk, such as the Willamette Valley where we live.

Sue Nackoney of Gentle Rain Farm was one of many Willamette Valley farmers who evacuated during last September’s fires. Her farm in Sandy, Oregon, ended up being only seven miles from the edge of the fire, which was moving 5 mph at one point. She told me that there were many challenges evacuating a farm.

She had to consider the health of her plants while she was away. The power was out to her irrigation well, meaning that she couldn’t water before leaving. She said that she covered everything she could with row cover and hoped for the best. She also had dogs and chickens to evacuate. She pulled their mobile chicken coop with her.

Even after it was clear that her farm was safe and she could return, the challenges continued. Her markets were cancelled because of dangerous air pollution, and plant growth slowed because of dark skies and missed rounds of irrigation. “I still feel like I have not recovered from the fear of that time,” she told me in June. “I came home this past Sunday and a new fire was somewhere nearby, leaving the skies thick with grey smoke, and I felt pretty stressed out.”

The risk of losing a home or farm to wildfires now feels like a reality for farmers across the region. Farmers are preparing by taking recommended steps to clear “defensible perimeters” around their homes and buildings, keeping some parts of their farm mowed to reduce fuel loads of dry brush. Damian Rohraff of Holy Sticks Farm on Vancouver Island, British Columbia, said that they are creating such spaces on their farm and also planting hedgerows to stop any potential fires. “A live hedgerow of willows doesn’t burn as easily and can stop or slow down some forest fires,” he said.

When possible, irrigation can also be used strategically during a red flag event. During last September’s red flag warning, once our power was restored to our well pump, we ran handlines along the upwind side of our farm for several days to create a band of moisture in the air and soil that hopefully could halt or slow fires.

But even when we are not in the direct path of fire, the resulting smoke has become a new summer feature. This was a concern for almost every farmer I spoke with. Many reported slowed plant growth and ash deposits on crops, but the potential harm to human health was the biggest worry. During the big fires of last September, the Air Quality Index ranked our region as “hazardous,” the most extreme ranking.

Siri said that they are “constantly questioning the sustainability of a farm plan that requires outdoor work in the midst of severe smoke.” Beth purchased ventilators and filters for the upcoming season. They also plan to use ski goggles to protect their eyes from ash.

I have heard similar solutions proposed on a regional farmer email listserv I follow, where this spring people were swapping tips on the best mask or ventilator solution for smoke, trying to find a balance of comfort and efficacy. At the very least, many farms and extension agents that serve the agricultural community are making sure they have stores of KN95 masks available for outdoor farm workers to wear during smoke events.

Preparing for the unexpected

While increased drought, heat, and wildfires are the most likely scenarios projected by current Pacific Northwest climate models, part of the projections for climate change in general is simply more variability. In other words, on some level, we need to be preparing for the unexpected, even as we prepare for what’s been predicted.

For example, how will all these factors affect the seasonal flooding events that many river valley farmers experience? We know that changes in climate will likely affect pest pressure, but in what ways? There are still many more questions than answers, but all the farmers I connected with on this topic reiterated the need to build resilience into all their systems as farming in general becomes riskier.

Many of those tactics are similar to what market growers already have learned to do to offset farming’s longtime risks. Delaney Zayac of Ice Cap Organics in Permberton, British Columbia, said: “We try to plant varieties that can handle these extremes, and we try to plant more, and be more efficient to offset the higher costs of growing.” He echoes other farmers too in saying that having more greenhouse space has helped their farm have some more control over climate and extend their shoulder seasons.

Much of this sounds like the tried-and-true advice found in Growing for Market for years now: carefully choose seed varieties, plant diversely over a long season, and work toward efficiency. But the stakes are higher now as we face more and more extremes — the Pacific Northwest farming game seems to be getting harder as it is getting hotter.

Katie Kulla lives and farms with her family in Yamhill County, Oregon. You can find Katie at www.OakhillOrganics.com and on Instagram: @katiekulla.