Integrated Pest Management (IPM) is a systematic approach to pest management to tailor strategies for each situation. The goal is to reduce pest damage of crops to an economically viable level, while minimizing the risks associated with use of chemical pesticides. This approach considers the effects of pesticides on not just the crops and workers, but also the wider environment. Organic and sustainable farmers, using Biointensive IPM, go further in avoiding use of all synthetic pesticides. They (we!) focus on restoring and enhancing natural balance and resilience in agriculture to create healthy plants and soil, better able to withstand attacks. Biointensive IPM includes controlling pests by physical and mechanical means (preventing the pest reaching the crop, or removing the pest from the crop), and incorporates environmental quality and food safety as both ecological and economic factors in farming decisions.

Conservation Stewardship Program

The Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) has a Conservation Practice Standard on IPM (Code 595), which as I write is under revision to “make it more relevant and applicable to organic and sustainable farmers, and to reflect the conservation benefits of organic and sustainable farming,” quoting the instructions to reviewers of the new draft.

The NRCS uses the mnemonic PAMS (which I find especially easy to remember!), for the sequence of four IPM steps - Prevention, Avoidance, Monitoring and Suppression. According to the likely severity of each particular pest, Prevention alone, or Prevention and Avoidance may be enough action. If the trouble is likely to be worse, Monitoring is used to assess if and when the Action Level has been reached and Suppression is needed.

Certified Organic producers are required by the National Organic Program (NOP) Regulation to use multiple Prevention and Avoidance strategies before using any Suppression strategy (and then use only approved inputs).

Prevention

Start at your yearly planning to focus on preventative strategies, and minimize opportunities for pests to get out of control. Preventative actions are also known as Cultural Controls.

Care for the soil, in order to grow strong plants better able to fend off attack. Regularly add organic matter of different types to enhance the biological, physical and chemical properties of the soil. Use a diversity of cover crops, keeping the soil covered with growing plants or crop residues whenever possible. Minimize soil compaction and hard-pan layers. Adjust pH to suit the crops being grown.

Plant resistant, pest-tolerant, regionally-adapted varieties when available.

Grow strong plants by careful spacing, planting at the right time, providing optimum water and nutrients, managing weeds to reduce competition for nutrients, and improving airflow.

Maintain good sanitation of equipment and clothing.

Promptly remove and destroy pest-infested plants.

Ensure that transplants are pest-free before planting.

Avoidance

After growing the healthiest plants possible, the next stage is taking actions to reduce the chances of a specific pest taking over. These actions are also known as Physical Controls. All these methods reduce problems without adding any new compounds into the soil.

Use good crop rotations so that it’s hard for pests in the soil to find new host crops.

Plant successions of the same crop distant from each other, and harvest the newer crop before the older one to minimize transfer of pests to the new planting. We do this with beans, cucumbers and squash/zucchini. Before we started buying the Pediobius wasp to deal with Mexican bean beetle, we used to plant more successions of beans, and flame the old plants when the pest count got too high.

Remove pest habitat, by mowing, pruning, clearing debris, grazing with livestock, hand weeding, or flaming.

Use organic mulches (e.g. spoiled hay or straw on potato plantings will greatly reduce the number of Colorado Potato Beetles that find the plants). Use reflective plastic mulches or those of a certain color to deter other pests (e.g. reflective mulches will deter aphids, thrips and whiteflies).

Use deterrents such as garlic spray or hot pepper spray against rabbits; soap bars against deer.

Grow transplants in a protected greenhouse and plant out once the starts are large enough to withstand most pests.

Use row covers to physically exclude pests. White polypropylene row cover is available in lightweight forms for insect protection in summer. We have found it very fragile and easily torn, so we often use thicker row cover, even in summer. If you have a serious insect problem and don’t mind single-use plastics, lightweight row cover might suit you fine. Hungry rabbits, though, chew holes in row cover, and are smart enough and big enough to chew out the squares between the reinforced grid of Agromesh type reinforced row cover! For warm weather use, we usually drape the row cover directly on the plants, without hoops. We don’t need to keep the cover from touching the foliage as we do in winter. For our fall broccoli and cabbage, we support row cover on ropes above the crop. The 83” (211 cm) width row cover will cover two rows at 34” (86 cm) spacing. Johnny’s now sells squarish hoops with special loops at the top to hold twine to support row cover.

We use row cover against cucumber beetles when we transplant or direct sow cucurbits. We keep the row cover on until the crop is flowering, then pack it away, so that the flowers can be pollinated. By then the bigger plants are better able to resist the pests. Row cover is one of the defenses against the Brown Marmorated Stink Bug, a devastating pest recently and accidentally introduced to the U.S.

We use row cover in summer on brassica transplants to protect against Harlequin Bugs and to reduce transplant shock. We remove it after about three weeks. We also use row cover on young eggplant transplants to protect against flea beetles, removing it when the plants flower and need pollination. We keep the seedlings covered in the cold frame while hardening off, and then do our best to cover the transplants promptly after setting them out. Sometimes we hose the plants with a jet of water to dislodge any flea beetles already there, while someone else follows immediately behind to spread the row cover. (By the way, not everyone knows that brassica flea beetles and nightshade (eggplant) flea beetles are not the same species, and don’t care for each other’s food, so don’t worry about setting out eggplant next to broccoli.)

Use polyethylene sheeting. In the UK, Carrot Rust Fly/Carrot Root Fly is a big pest, and prior to the invention of row cover, organic growers made 3’ (1 m) high fencing around carrot beds, usually of framed panels of polyethylene sheeting. This works because the Carrot Rust Fly flies in close to the ground. It also provides wind-protection and a mini-greenhouse effect, but is more work than floating row cover.

Use netting. A few years ago I brought back from the UK a small roll of Enviromesh Insect Netting to try out. Something similar is available online or by mail order from Purple Mountain Organics, in Tacoma Park, MD. www.purplemountainorganics.com: ProtekNet Insect /Pest Netting. A roll 82”x 328’ (2.08 x 100 m) sells at $339.99 in 2011. Made from UV resistant 80 gm/m² knitted polyethylene, it transmits 83% of the light and has a lifespan of 7-9 years. The mesh size is 0.0394” x 0.0335” (1 x 0.85mm). They also sell a lighter weight ProtekNet Insect/Pest Control Netting 25 gm/m², with a lifespan of 3 seasons. The price in November 2011 is $432 for 6.9’ x 820’ (2 x 250 m), also available in smaller pieces. They recommend burying the edges in the soil. Farmtek has an insect screen fabric for doors, vents and hoophouses.

Growers pestered by cutworms or cabbage root fly use collars around each transplant when they set them out.

Use mixed plantings (intercropping) to maximize diversity of insects and other beneficial organisms.

Use hedgerows, field borders, and sections of planting beds for farmscaping to attract beneficial insects – plant 5% of the crop area to insectaries. We plant Sweet Alyssum in our spring broccoli patch to attract predators of aphids and of caterpillars. See the article at www.extension.org/article/18593

Provide habitat for bats, insectivorous birds, spiders, birds of prey and rodent-eating ground predators (snakes, bobcats). We encourage black snakes to live in our root cellar and eat any mice that come in. We have installed bat-boxes on barn walls near our garden to reduce the number of mosquitoes.

Plant perimeter trap crops to lure pests from the food crop. Destroying the trap crop in a timely way, before the pests move on to the food crop, is an essential part of this strategy. Trap crops of zucchini may be the best immediate hope for catching the Brown Marmorated Stink Bug.

Physically remove pests, by hand-picking, by spraying with a strong water spray, by flaming, vacuuming, or by using a leaf-blower to blow bugs into a collecting scoop.

Solarize soil in the summer to kill soil-dwelling pests, as well as diseases. Cover cultivated damp soil with clear plastic for 4-8 weeks in high summer, during which time the area is out of production.

Monitoring

The appearance of a pest does not necessarily require killing it. The Action Level or Economic Threshold is the point at which the losses from the pest warrant the time, money and ecological disruption put into applying control measures.

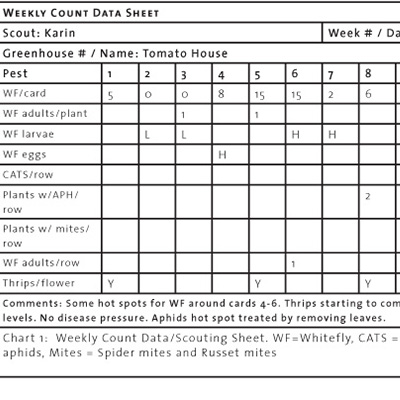

Make a habit of walking the fields regularly (weekly) to scout for trouble as well as for natural enemies of pests. Learn to recognize bugs of all kinds, and understand their lifecycles and their enemies. Record what you find where and when. Take a hand lens. Monitor the results of any measures previously taken.

Scout vulnerable crops frequently (daily) at critical times.

Photograph or capture insects you are unsure about and identify them from websites or books, such as Whitney Cranshaw’s Garden Insects of North America.

Use phenology to predict the likely arrival of key pests. Phenology is the study of seasonal and yearly variations in climate by recording regular plant and animal life cycle events each year. A visible change can be used as an indicator that another species is also likely to be changing. For example, we expect brassica flea beetles when the redbud blooms, and bean beetle eggs to hatch when the foxgloves bloom.

Weather forecasting helps with deciding when pest outbreaks are more likely. Mexican Bean Beetle eggs seem to prefer hatching in cloudy weather. Use any available online pest-specific forecasting sites. These sites combine scouting and reporting of outbreaks with weather forecasts of temperature and wind direction to make a forecast map

Record and use Growing Degree Days to help predict pest outbreaks. The development rate of many insects, from hatching to maturity, normally depends on temperature. By keeping temperature records, and calculating accumulated heat, it is possible to predict when pest outbreaks may occur during a growing season, even though temperatures vary from year to year. GDDs are the accumulation of each day’s Growing Degrees above the baseline level. I haven’t started using this method yet, but Japanese beetles appear at a GDD level of 850, on a base of 50°F, and corn earworm somewhere between 150-490 GDD on a base of 54°F. Some weather forecast websites have a GDD Calculator, such as www.weather.com/outdoors/agriculture/growing-degree-days

Set traps and lures (sticky traps and pheromone traps). Usually these will not significantly reduce the pest population, but are useful for indicating whether or not a certain pest is on your farm, so that other measures can begin as early as possible. Some, such as the pheromone lure for cucumber beetles, can make enough difference on some farms.

Good record-keeping helps in improving effectiveness. Record the pest name and population, date, which fields, which input (if any), relative success of action, date repeated, equipment used, cleanup method, comparison with methods used previously, and overall evaluation. Keep learning, and applying what you learn. “Never make the same mistake two years running” is a mantra on our farm.

Suppression

When the established Action Level for a particular pest has been reached, and prevention and avoidance strategies have been exhausted, biological, microbial, botanical, mineral (and for non-Organic growers, chemical) control measures can be used to reduce or eliminate that pest or its impact while minimizing environmental risks. Design a series of measures that work together, to ensure that one action does not mess up another. Choose the least toxic materials and the least ecologically-disruptive methods. Precision equipment, calibrated sprayers and focused nozzles all help minimize the collateral impact on the environment. Be aware of sensitive areas, such as waterways, slopes, woodlands and habitat of vulnerable species. Be aware of better times to spray, eg for sprays that kill honeybees, use them in the very early morning or at dusk when they are not flying. For compounds that break down in sunlight, spray at dusk for maximum effectiveness and minimum amounts.

Biological Control involves either introducing beneficial predators or parasites of the pest species, or working to boost populations of existing resident predators and parasites. Most years we buy the Pediobius wasp parasite of the Mexican Bean Beetle. Some years populations are not high enough for us to need the parasites.

Microbial Controls include fungi, bacteria and viruses that kill pests. Bt (Bacillus thuringienisis), a species of bacteria, is the best known microbial control. One strain kills caterpillars, another mosquitoes, another Colorado Potato Beetles. Spinosad is a fermentation product (no longer live material) of a soil microbe containing an enzyme that kills thrips, leaf miners, most caterpillars and some other insects. We use it against Colorado Potato Beetles on our March-planted crop. The June-planted potatoes don’t need any CPB control beyond the hay mulch we roll out to keep the soil cool and moist. We have also used Spinosad against the vegetable weevil larva when they took over our winter hoophouse turnips and greens. Spinosad, insecticidal soaps and pyrethrins are 3 insecticides available in OMRI-approved forms that are the most promising so far for dealing with the Brown Marmorated Stink Bug.

Botanical Control uses plant-based products for pest control. An example is neem oil, which degrades in UV light in 4-8 days and must be reapplied if the organisms are still around. Rotenone and pyrethrin are two botanical insecticides effective against aphids, stink bugs, beetles, stink bugs, squash bugs, cucumber beetles, vegetable weevils, and other pests. They are generally strong broad-spectrum insecticides with short-term results.

Inorganic (Mineral) Controls, also known as Biorational Disease Controls, include oils and soaps. Several of these need to be used with caution if the plants and the planet are to survive the treatment.

Petroleum-based horticultural oils control soft-bodied insects, such as aphids, spider mites, and whiteflies, (rather than hard-bodied insects such as beetles). Most are not approved for Organic use, sometimes because of secondary ingredients. As an alternative, vegetable oils and fish oils are available in some Organic formulations. Insecticidal soaps are made from potassium salts of fatty acids. If used too heavily they can damage foliage. They are effective on soft-bodied insects, and are one of our choices for dealing with early spring outbreaks of aphids in the hoophouse. After reducing the pest numbers, we collect hibernating ladybugs and bring them in for a feast. Sulfur is sometimes used against spider mites. Kaolin clay, besides being a protective layer on crops, can suppress feeding in striped cucumber beetles, flea beetles, thrips and grasshoppers.

Synthetic/Chemical Controls are not allowed on certified Organic, transitioning-to-Organic or Certified Naturally Grown farms, and not used on biointensive or sustainable farms. There are some other farmers who may choose to use chemical controls when facing a plague and after trying and failing with sustainable methods.

Non-insect Pests

We tend to think mostly of insects when we use the word “pests,” but of course there are also microscopic pests and vertebrate pests. Vertebrate pests include mammals such as deer, rabbits, groundhogs, armadillos and voles, as well as birds such as pheasants, pigeons and crows. Physical barriers, strong deterrents such as vigilant dogs or cats, and hunting are the three main options.

Resources

eXtension Insect Management in Organic Systems has many useful short articles on specific facets.

www.extension.org/article/18593

ATTRA Organic IPM Field Guide, an attractive 9 page poster format introductory document: attra.ncat.org/attra-pub/summaries/summary.php?pub=148

ATTRA Biointensive Integrated Pest Management. Free digital copy: www.attra.ncat.org/index.php/ipm.html

SARE Handbook Manage Insects on Your Farm: A Guide to Ecological Strategies: www.sare.org/content/download/29731/413976/file/insect.pdf

Garden Insects of North America. Whitney Cranshaw (Princeton University Press). A guide to insect identification from www.growingformarket.com; 1-800-307-8949.

Pam Dawling is the garden manager at Twin Oaks Community in Louisa County, Virginia. Her book, with the working title Growing for a Hundred, is scheduled to be published this year.

Archive

Learn how to manage pests ecologically

By Pam Dawling

January 1, 2012

Insect pollination is essential to many vegetable and fruit crops, including tomatoes, squash, pumpkins, watermelons, blueberries, blackberries, apples, almonds, and many others. In the case of watermelons, there will be no fruit without pollination. Some vegetables don't require pollination to set fruit, but pollination by bees will result in larger and more abundant fruits. Nearly 75% of the flowering plants on Earth rely on pollinators to set seed or fruit, as well as one-third of our food crops, and most pollination is performed by honey bees, native bees, and other insects.

Insect pollination is essential to many vegetable and fruit crops, including tomatoes, squash, pumpkins, watermelons, blueberries, blackberries, apples, almonds, and many others. In the case of watermelons, there will be no fruit without pollination. Some vegetables don't require pollination to set fruit, but pollination by bees will result in larger and more abundant fruits. Nearly 75% of the flowering plants on Earth rely on pollinators to set seed or fruit, as well as one-third of our food crops, and most pollination is performed by honey bees, native bees, and other insects.