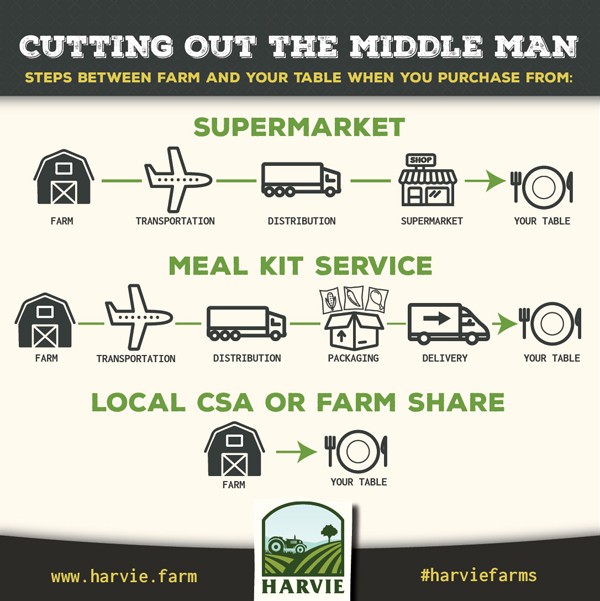

I love CSAs. What could be better? A direct link from farmer to consumer, commitment from the consumer for a whole season, up-front operating capital, a captive social network, community building, let alone the farmer’s ability to tailor the CSA share to best meet the farm’s needs.

While there are many different types of CSAs, a common model looks like this: a flyer or brochure promotes a farm’s CSA, and outlines a mechanism for enrolling in, and paying for, a share in the CSA program. A tri-fold brochure may have a tear off sign up section with price options to send in to the farm with payment. In exchange for a certain amount of money, the consumer receives a number of weeks of CSA share distribution.

As an example, a farm’s CSA full share may cost $500 for 20 weeks of seasonal produce, distributed from mid June until late October. That works out to an average of $25 per week sales income for the farm.

Some CSAs are small and some are large or very large. In the above scenario, a farm may have a 100 member CSA with $50,000 CSA sales income. Or maybe 200 members with $100,000 sales income. Many CSAs have even more, with sales in the $200,000 to $300,000 range. That’s a chunk of change. CSA income can represent a significant portion of the farm’s total sales income, but is it profitable?

Why do I have to bring up the subject of profitability if CSA sales are good, members are happy, and the farm is in the black? I used to think that the CSA model didn’t necessitate crop enterprise analysis that I feel is so important with non-CSA farms.

Crop enterprise analysis is a fancy term for cost/benefit. Of the different things you produce on your farm, each has its own costs of production, sales revenue, and resultant profit (or loss). Whether raising six feeder pigs, a quarter-acre of carrots, or making apple cider, each has its own income and expenses that contribute to the overall farm’s net profit. If you grow 30 different types of vegetables, each has its own level of profitability, with some more than others. These all get averaged into your farm’s year-end net profit. I can almost guarantee you that each crop’s profitability won’t be equal. That said, focusing on more profitable farm products can only help increase your farm’s overall bottom line, a very desirable result.

If you are unfamiliar with crop enterprise budgets, they can be simple to overly complex. Tracking the labor input is usually the toughest nut to crack, because it is best done in season when things on the farm are at a fever pitch. Other costs, and sales income, are often documented with a paper trail, making them easy to input. All crop budgets list sales income, various expenses, and net profit. To see some easily digestible examples online, check out Penn State University and University of KY enterprise budgets:

Extension.psu/business/ag-alternatives/farm-management/ Click on Budgeting. Table 1 is for crop budgets, Table 2 is for Livestock.

www.uky.edu/Ag/NewCrops/vegbudgets13.html Click on Vegetable and Melon Budgets to download.

And then, I can always recommend a good book on the subject……

Since CSA farms are often sold more as a package of ‘pay one fee upfront, and get a season’s worth of produce’, my old thinking was enterprise analysis seems unnecessary added work. But I’ve changed my tune. Here’s why.

Imagine a CSA continuum of profit, where the left endpoint is the most profitable CSA possible, and the right side, is the least profitable CSA. To illustrate my point, let’s say I have two different CSAs: a very profitable ‘All-Kale’ CSA, and a much less profitable ‘All-Corn’ CSA.

For my All-Kale CSA, I distribute 10 bunches of kale (valued at $2.50/bunch) every week for 20 weeks. (If I lived in a kale-loving, densely populated area, or had kale-friendly restaurants, I might be able to sell enough shares to make it work). With my All-Corn CSA, members receive 5 dozen ears of sweet corn (valued at $5/dozen) each week for 20 weeks. (I may find enough farm stands and restaurants who want that much sweet corn).

Sweet corn is my favorite dog to kick profitability-wise, only because it is such a high-demand item that is often undervalued. Kale is one of my profitability examples, because it usually is.

Somewhere between these two end points of profitability lies the diversified vegetable CSA. Depending on the crop selection a farm chooses for their CSA, the place on the continuum will be either closer to the All-Kale or All-Corn CSA (or possibly smack dab in the middle).

The more crops you select for your CSA that are more profitable moves your CSA to the left. The more unprofitable a crop mix, your CSA moves to the right.

As you move your CSA to the left, you can pay yourself more, pay your employees living wages, make needed repairs, invest in equipment that makes you even more efficient and profitable, or save money for kids’ college educations, your retirement, and family vacations.

CSAs closer to the right-hand side scarcely reward the farmer, perennially depend on cheap labor or apprentices, forego needed repairs, have less for capital purchases, college tuitions, retirement savings or vacations. A recipe for burnout, and possible end to the farm business.

So how to select the right crops so you can be as profitable as possible? Begin by thinking about the overall goals for your farm. Next, take a new and closer look at your current crop selection, with an eye towards increased profitability. Can certain crops be eliminated, or bought in? Multi-farm CSAs allow specialization in fewer crops, often at greater efficiency and profitability. Profitable sweet corn growers exist, often because they are focused on that crop.

I don’t want to decrease diversity necessarily, just question it. CSA members will still have to go elsewhere to get their coffee, chocolate, avocados and bananas. Your CSA newsletter is a great vehicle for explaining why you don’t grow certain vegetables, or crops at different times in the season (like spinach in spring and fall only, with salad greens as a replacement green in midsummer).

One ultimate role as farmer is to make sure your farm survives. No one else will do that, unless you hire someone to do it. You can be the best grower, marketer, innovator, and mechanic, but unless your farm survives financially, all that goes out the window because your farm will be out of business.

My goal is to see more prosperous, content farmers who are less stressed out and prone to burnout. The CSA sales avenue holds that potential. But don’t let significant gross sales income lull you into complacency and avoid the ultimate economic sustainability that all farms need. Pay attention to your farm’s economic health; it will be a win-win situation.

Richard Wiswall is the co-owner of Cate Farm in Vermont and the author of The Organic Farmer’s Business Handbook, available from Growing for Market for $35 ($28 for subscribers — see page 2 for information on how to get the discount.) Visit growingformarket.com or phone 800-307-8949.

It’s not too late for online/preorder seedling sales, farmers market custom bags, and We Give a Share

It’s not too late for online/preorder seedling sales, farmers market custom bags, and We Give a Share

Farmer to Farmer Profile

Farmer to Farmer Profile

Why is the flower micro-farm best suited to a laser focus on one or two enterprises versus a balance of several? It is because of the long maturity of flower crops and the specific and conflicting demands of different types of flower enterprises. For example, some of the most common ways for farms to sell their flowers are at a farmers market, wholesale, from a flower stand/truck, a CSA, and weddings/events. These outlets can be compared on their need for similar types and quantities of flowers.

Why is the flower micro-farm best suited to a laser focus on one or two enterprises versus a balance of several? It is because of the long maturity of flower crops and the specific and conflicting demands of different types of flower enterprises. For example, some of the most common ways for farms to sell their flowers are at a farmers market, wholesale, from a flower stand/truck, a CSA, and weddings/events. These outlets can be compared on their need for similar types and quantities of flowers.

For most established growers, the easiest place to start selling flowers will be mixed bouquets and single stem/small bunch retail sales. These are the flowers you can sell to your existing customers and they are easy to incorporate into farmers market, CSA, and grocery sales. But there are lots of other outlets out there, including florists, weddings and events, business subscriptions, value added products, and wholesalers.

For most established growers, the easiest place to start selling flowers will be mixed bouquets and single stem/small bunch retail sales. These are the flowers you can sell to your existing customers and they are easy to incorporate into farmers market, CSA, and grocery sales. But there are lots of other outlets out there, including florists, weddings and events, business subscriptions, value added products, and wholesalers.

I made a trek out to Wisconsin in June. I’ve been lucky enough to visit this gorgeous state a few times, and I was glad to return. Wisconsin is the state with the second most organic acres in the country, behind California. It’s been an important crucible for the organic ag movement since the beginning. Out of the 177 of Chris Blanchard’s Farmer to Farmer podcasts, 21 featured Wisconsin-based businesses. From that list I chose two farms to visit and interview for this column.

I made a trek out to Wisconsin in June. I’ve been lucky enough to visit this gorgeous state a few times, and I was glad to return. Wisconsin is the state with the second most organic acres in the country, behind California. It’s been an important crucible for the organic ag movement since the beginning. Out of the 177 of Chris Blanchard’s Farmer to Farmer podcasts, 21 featured Wisconsin-based businesses. From that list I chose two farms to visit and interview for this column.

“CSA is dead” is a refrain I have heard from multiple farms in the past few years. I started to hear rumblings of a problem with the CSA model in 2014 through the CSA Farmer Discussion group that I manage on Facebook which brings together over 2,500 CSA farmers from all over the world. Farmers reported that they were having trouble attracting and retaining membership.

“CSA is dead” is a refrain I have heard from multiple farms in the past few years. I started to hear rumblings of a problem with the CSA model in 2014 through the CSA Farmer Discussion group that I manage on Facebook which brings together over 2,500 CSA farmers from all over the world. Farmers reported that they were having trouble attracting and retaining membership..jpg)

It’s an incredibly cool, clear and dry July day in Massachusetts as I make my way to Brookfield Farm. Dan has arranged for me to visit at 2PM on a Thursday so I can see this bustling CSA farm at distribution time. I arrive just before the appointed hour, and see the last details of the setup being handled by apprentice Ellen. Dan and Karen are bustling around the corner, checking that the room is ready for the deluge of customers to come.

It’s an incredibly cool, clear and dry July day in Massachusetts as I make my way to Brookfield Farm. Dan has arranged for me to visit at 2PM on a Thursday so I can see this bustling CSA farm at distribution time. I arrive just before the appointed hour, and see the last details of the setup being handled by apprentice Ellen. Dan and Karen are bustling around the corner, checking that the room is ready for the deluge of customers to come.