For the 50th anniversary of Earth Day on April 22, 2020, we ran Brett Grohsgal's article "Breeding crops for resilience to a changing climate" in our April magazine. On-farm breeding is one of the many strategies local farms can use to adapt as the world changes around them.

One of the nice things about being around for 29 years is that we have a large archive of articles (over 1,600) to draw upon. In his article, Brett references three other articles from 2002 (!) where he gave a more in-depth picture of his breeding strategy. The links to all four articles are here:

Link to "Breeding crops for resilience to a changing climate" from the April 2020 magazine

Link to "Saving seed makes sense, Part 1" from the August 2002 Growing for Market

Link to "Seed saving, Part 2: The tasks detailed" from the September 2002 Growing for Market

Link to "Seed saving, Part 3: Genetic management" from the October 2002 Growing for Market

Strategies to use on your farm: a breeder’s perspective

Strategies to use on your farm: a breeder’s perspective

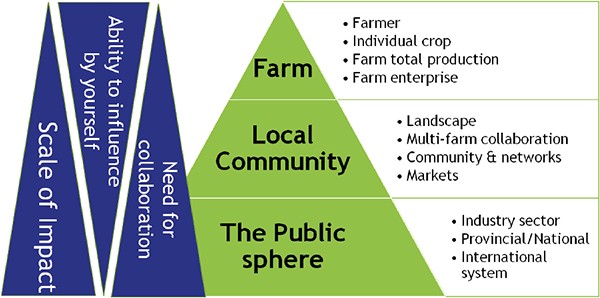

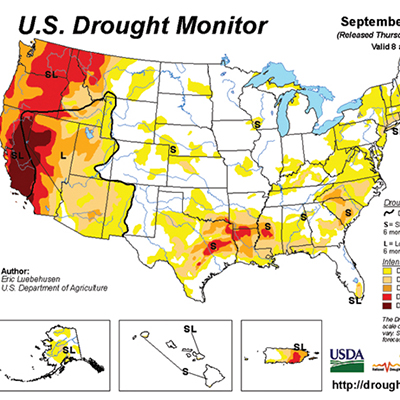

While lobbyists and some politicians have managed to paint the climate change debate as a partisan issue, farmers are increasingly feeling the impacts on their production environment and asking themselves: How can I re-think my operation in order to continue farming with increasingly unpredictable weather conditions? In this article, I am summarizing my lifelong quest for understanding climate resilience and offer a self-assessment template to help you plan for more resilience.

While lobbyists and some politicians have managed to paint the climate change debate as a partisan issue, farmers are increasingly feeling the impacts on their production environment and asking themselves: How can I re-think my operation in order to continue farming with increasingly unpredictable weather conditions? In this article, I am summarizing my lifelong quest for understanding climate resilience and offer a self-assessment template to help you plan for more resilience.

In the April 2020 issue, Brett Grohsgal’s article “

In the April 2020 issue, Brett Grohsgal’s article “