By Thorsten Arnold

While lobbyists and some politicians have managed to paint the climate change debate as a partisan issue, farmers are increasingly feeling the impacts on their production environment and asking themselves: How can I re-think my operation in order to continue farming with increasingly unpredictable weather conditions? In this article, I am summarizing my lifelong quest for understanding climate resilience and offer a self-assessment template to help you plan for more resilience.

First, impacts of climate change on farming systems are complex, and farmers are well-advised to be thoughtful about what personal goals they set themselves with respect to climate change. Some goals, like “increasing production yields per acre” or “ensuring a minimum total production” are simple to measure and thus often preferred by administrators, business analysts and researchers. But what good is simple measurement, if farmers achieve these goals at the expense of their financial viability, their personal health, or their social networks?

Researchers have found that it is more useful to aspire a much more fuzzy and complex goal: climate resilience. Myself, I started to think methodologically about adapting to climate change in 2001, when I found myself thrown into a United Nations conference in Marrakesh, Morocco, where the Kyoto Protocol was detailed out. This conference already shifted the public eye to those most impacted by climate change, by asking: What types of climate threats are we facing? Who is vulnerable to these threats, and in which ways? How can those who are vulnerable react and adapt? How can societies support their efforts and reduce exposure to climate risks?

In the last few years, explicit planning approaches for climate resilience have taken form. In this article, I am drawing on the teachings of Clara Nicholls and Miguel Altieri, who have been deeply involved in building the agroecological movement in Latin America where they interviewed hundreds of farmers on how they have built climate resilience. And I am drawing on my personal work experience – as husband of a market gardener, as ecological farming researcher, advocate, and food chain consultant.

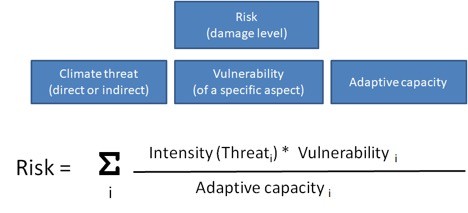

Clara Nicholls defines the goal of climate resilience as “the ability of a farming system to absorb climate-related disturbances and adapt to stress and change while retaining its productive structure and yield.” A resilient farm is not immune to climate threats – but it manages risks successfully by reducing vulnerability and building adaptive capacity (Figure 1), such that after being exposed to severe climate stress, the farm bounces back swiftly and remains viable.

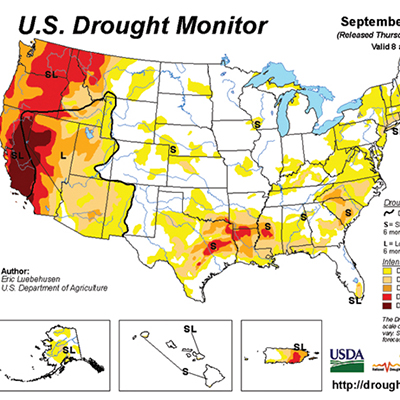

When discussing climate threats with farmers, they identified direct weather impacts that hurt production, such as excessive rain and drought, hailstorm and destructive winds, and untimely heat or frost. Farmers are also conscientious of indirect climate impacts: market prices reacting to climate stress elsewhere, input costs peaking (sometimes driven by climate speculators); politicians reacting hastily with policies that have unintended consequences.

The current vilification of ruminant impacts is a good example: instead of focusing on adverse production practices and promoting climate-beneficial grazing, consumers reject red meat without recognizing the enormous opportunity! So, farmers may find indirect climate impacts – the policies, market reactions, and consumer confusion – to be more problematic than direct climate threat itself!

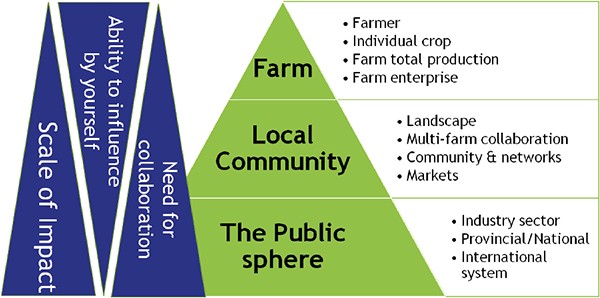

For building climate resilience, most of us are mainly concerned about our own farm, our own crop and livestock – but farmers also realize that in times of distress we need each other. Farmers can influence three general realms (Figure 2):

The farm: an individual crop, the entire production, the farmer and staff, and the farm enterprise;

The local and community: the agroecological landscape, our community of likeminded farmers that we work with and rely on, our local market that we sell to, and our networks that we learn with and communicate through; and

The larger public sphere: the farming sector, state and national policies, financial services, and the international market.

Many discussions on farm resilience focus on the production system: how to build soil health for improved water and nutrient retention, how to design water infrastructure for storage, drainage, and irrigation, invest into greenhouses, move toward no-till, choose plants that yield under water stress, diversify the crop mix, and tweak the production systems such that we are less susceptible to weather extremes.

I call these production measures our first line of defence – and farmers are well advised to make use of these strategies. There is probably no better strategy for a resilient crop than healthy soil with high water infiltration, high capacity for holding nutrients and storing water, and reduced erosivity. And farmers can diversify their crops and varieties, such that the risk of loss is spread out. Though all bets should not be on modifying the production approach.

Even at farm level, there are other ways to increase resilience. After another dire season in Ontario, many market gardeners burned out. Some quit farming entirely or found new employment with lucrative indoor cannabis production. What are your strategies to prevent burn-out? I personally love the practice of Aikido – practice induces deep trust and connection with my training partners, which creates a feeling of health and peace in me. Others dance or do theatre for similar benefits. What are your strategies to divert your mind from the farm, relax your body, and replenish your needs for connection?

Holistic planning also empowers your farm. The grazier Greg Judy talks about being the first to sell parts of his herd when he foresees a shortage of feed– at a time when he still gets a good price. When all others sell and the beef prices crash, he may even be ready to re-stock and benefit from a low price! At our farm, we explicitly decreased our reliance on crop sales for income, by offering courses, consulting, gardening workshops and transplants. This way, we reduced our farm’s financial reliance on our crops. What type of income diversification would fit with your farming goals?

As members of their community, farmers only have control over the “private” aspects of their life while the food system is really governed by our collective decisions. There are our farmer peers – who share equipment, help one another to fill CSA boxes, offer mentorship or just a compassionate ear. Farmer-led research and coordinated variety trials are increasingly important – we need each other for that.

(adapted from Altieri et al., 2015)

Old-order Mennonites are masters in co-developing appropriate technologies. This greatly enhances their capacity to adapt to new circumstances quickly, because they crowdsource ideas and test a number of prototypes simultaneously on many farms. Or, collaborative marketing can open new opportunities that stabilize income, especially outside of the CSA and farmers market season. How do you deal with a bumper crop, or a massive b-grade harvest that is not fit for market?

At home, we can’t justify owning processing equipment for random harvest peaks but would love to have access to community processing. Climate change will increase this need further. In changing climate conditions, community solutions will become more important, but in the isolation of farm life and the competitive mindset of our society, it is easy to neglect these networks. Working together is not easy. It requires a different set of skills than supervising farm workers. When disaster strikes, communities that already have built collaborative skills will be more resilient.

Finally, farmers can speak up and, as a sector, can help shape the public sphere. Not as individuals, but as members of organizations that research, educate, create market power, and lobby government, funders, and academic institutions. Extreme climate events will trigger strong political responses, and we’d be well advised to have a strong and representative voice that reflects our true needs, not those of corporate sponsors that currently dominate agricultural lobbying.

Working through organizations is difficult, and many farmers chose this career because they don’t like to have hierarchies control their life. This left the political sphere to corporate lobbyists and food advocates from urban centers, while political awareness has faded for what really happens in our countryside. So independent farmer organizations are a necessary communication channel for reaching urban decision makers. Again, we need to build these organizations before we really need to rely on them, pre-emptively.

Climate resilience is such a complex concept, how can it inform decisions on your own farm and your role in your social network? Certainly, no individual can do everything. Yet, climate resilience offers a lens for prioritizing where each one of us puts our limited resources. There are no-brainers with multiple benefits, which should be high on everyone’s list: build soil health, minimize input and overhead costs, diversify crops and markets, establish strong relationships with buyers who value you for what you do and who you are, join and build an inspiring network of peers. Formulating a clear holistic goal, and a plan for how to achieve this goal, empowers you with intentionality and focus. That’s a very good starting point.

I believe that we can go one step further and develop explicit plans for building the climate resilience of our farms and our communities. Building on concepts and methods from Clara Nicholls and Miguel Altieri, I developed a planning exercise with four assessment steps:

Identify the top three(ish) climate threats, and describe how these impact your crop, your farm infrastructure, your staff, your market and network, and your mental and physical health.

List all income streams of your farm that are affected by each climate threat, and how long it would take to recover these. For each, estimate how relevant this is to your farm’s viability, separating out short-term impacts (e.g. sales and cashflow) and long-term impacts (e.g. erosion and loss of buyers). Score each income stream from 1 (low importance) to 4 (very significant importance), at both temporal horizons. These are your farm’s vulnerabilities.

How would you react when the climate threats actually occur? What resources would you summon to mitigate the worst impacts? How effective would these efforts be in curbing the damage? This is your adaptive capacity. For each income stream from (List 2), score your reactive capacity between 1 (poor) and 4 (very strong).

The risk that each income stream is exposed to is calculated by dividing the vulnerability by your reactive capacity. Where are your farm’s main risks?

Such a quantitative assessment exercise seems easy, but there are many ways to drill down into details. You can define one or many vulnerability indicators for each income stream. Many reactive resources can easily be used up! Be concerned if your reactive strategy is “work overtime” again and again – almost certainly it will cause burn-out. And there cannot be a resilient farm without a resilient farmer!

Also, be aware about “asking peers for help” – they probably are battling the same problems simultaneously. Once you know your vulnerabilities, and you understand your reactive capacity and your reactive resources, and you can identify those activities that face highest risk, you are ready to develop abatement strategies and a plan of action.

In summary, farmers can choose to reduce vulnerability and increase reactive capacity. We can do so by focusing on individual benefits for our own farm, or collaborating with peers to improve our community resilience, or shaping the public sphere through organizations. Not everyone can do all of it simultaneously – and as a group, we don’t need to. Yet, we can be smart about how we coordinate our own efforts with the efforts of others and contribute to community efforts based on our personal skillset.

System theorists call the structure of this problem a “prisoner’s dilemma.” Farmers have an incentive to focus all their efforts on their own farm, while hoping that others will build community and deal with the public sphere. Yet, if all farmers hope to rely on others for community building, it just won’t happen and we will all lose out. Building climate resilience is thus not only something that happens on all of our farms, but also about how we work together as a movement with a common cause.

Changes at Persephone Market Garden

At Persephone, we suffered three poor seasons in a row – a dry one, a wet one, and one that started way too dry and then became far too wet. After three depressing years, we had to make a choice: either stop farming, or farm differently. We chose the latter.

After participating in a no-till organic veggie workshop by Paul & Elisabeth Kaiser from Singing Frog Farms, we decided to adapt their methods because it makes sense to us. We basically stopped using the tractor on our field. For weed management, we use occultation with landscape fabric or solarization with clear plastic. We transplant almost everything, because we can protect our fragile transplants from adverse weather until they are strong and give them a head start on the weeds.

Working manually, we can access the field any time! We just pull off the cover when rain gives us a short break. Additionally, we also use lots of row cover and mulch – preferably switchgrass straw. This simple change has catapulted us from one of the latest harvesters to one of the earliest in our region, and we harvest almost twice as much per row foot. Farming is fun again, and our soil feels much better even in our first year of conversion.

Beyond production, we have also made strategic changes. I have stepped back from day-to-day farming work to focus on specific farm projects (a greenhouse, a pond, some repair) and on building resilient food systems as a freelance consultant. In an earlier issue of this magazine, I reported on lessons from setting up a cooperative online farmers market that has now broken even and is growing into a community hub! (See Rural online farmers market: a model for the future in the April 2018 GFM).

Recently, we piloted the first “Barn Academy” on climate resilience – a regenerative emersion that targets citizens who suffer from eco grief and don’t know what to do. We teach the concepts of regenerative agriculture, approaches how to deal with eco grief, and learn how to become effective agents of change. Finally, we are developing a farm & forest school on our property that teaches children the ability to enjoy and connect with nature.

References:

Altieri M, Nicholls-Estrada CI, Henao-Salazar A, Galvis-Martínez AC, Rogé P. Didactic toolkit for assessment of resilient farming systems. Third World Network, Sociedad Científica Latinoamericana de Agroecología (SOCLA), and REDAGRES. 2015.

Thorsten Arnold works as a food system advocate and value chain consultant. He co-owns biointensive Persephone Market Garden that is managed by his wife Kristine. After a few difficult weather years and inspired by Singing Frogs Farm, Kristine adopted no-till practices and upgraded most infrastructure. Thorsten studied marine sciences and researched climate change from various perspectives, and options for mitigation and adaptation. Thorsten recently developed a course, “Planning for climate resilience on your farm.”

For the 50th anniversary of Earth Day on April 22, 2020, we ran Brett Grohsgal's article "Breeding crops for resilience to a changing climate" in our April magazine. On-farm breeding is one of the many strategies local farms can use to adapt as the world changes around them.

For the 50th anniversary of Earth Day on April 22, 2020, we ran Brett Grohsgal's article "Breeding crops for resilience to a changing climate" in our April magazine. On-farm breeding is one of the many strategies local farms can use to adapt as the world changes around them.