I wrote an article for Growing for Market on Succession Planting in May 2006. I also do presentations on the topic and have a slide show on Succession Planting, which you can see on SlideShare.net (search for my name, then click on the presentation you want to view). In this article I will be applying the principles to winter hoophouse crops, in order to provide continuous harvest of important crops, avoid gluts and shortages, and use every inch of that valuable real estate.

Below: The author’s winter hoophouse at Twin Oaks in Virginia. Photo by Kathleen Slattery.

For the purposes of this article, I’ll assume you already have a pretty good idea of how much of which crops you want to grow and are looking to tweak planting dates for best results and find more ways to shoehorn in more crops. You already know the rate of growth of cold-weather crops is much faster inside and the crop quality, especially for leafy greens, is superb. You’ve noticed that plants tolerate much lower temperatures than outdoors; they recover in the pleasant daytime condition. Salad greens in a hoophouse can survive nights with outdoor lows of 14°F air temperature (–10°C). Add thick row cover and they can survive an outdoor low of -12°F (-24°C). Leafy greens, especially those which produce one pound or one head per square foot, are usually the highest earners.

Getting ready

We start with a blank map of our hoophouse beds, roughly to scale, and a schedule from last year of what we grew along with review-type notes on what worked and what didn’t. Our schedule has a column for Harvest Start date and one for Harvest Finish date. In tiny print in these columns we include the dates from recent years, leaving plenty of space to write in results for the current year. We look at the ideal finish dates for our high summer crops, and which crops were where last winter, then pencil in the main space-using crops. For us those are head lettuce, spinach, kale, turnips, and a range of the larger Asian greens. We write the planting dates and the space needed, on the blank map, then look at the remaining space in each bed. We make a list of all the little crops we hope to fit in, along with planting dates. Then we try to fit it all in, in a way that makes sense with the planting dates (we like to plant one or two beds at a time, through September and October – other growers might prefer to clear the whole hoophouse at once). We write in the harvest dates, and plan follow-on crops where possible. Finally we draw up a planting schedule in date order. Before planning successions or follow-on crops, it is important to get an idea of how long the first round of crops will be in the ground.

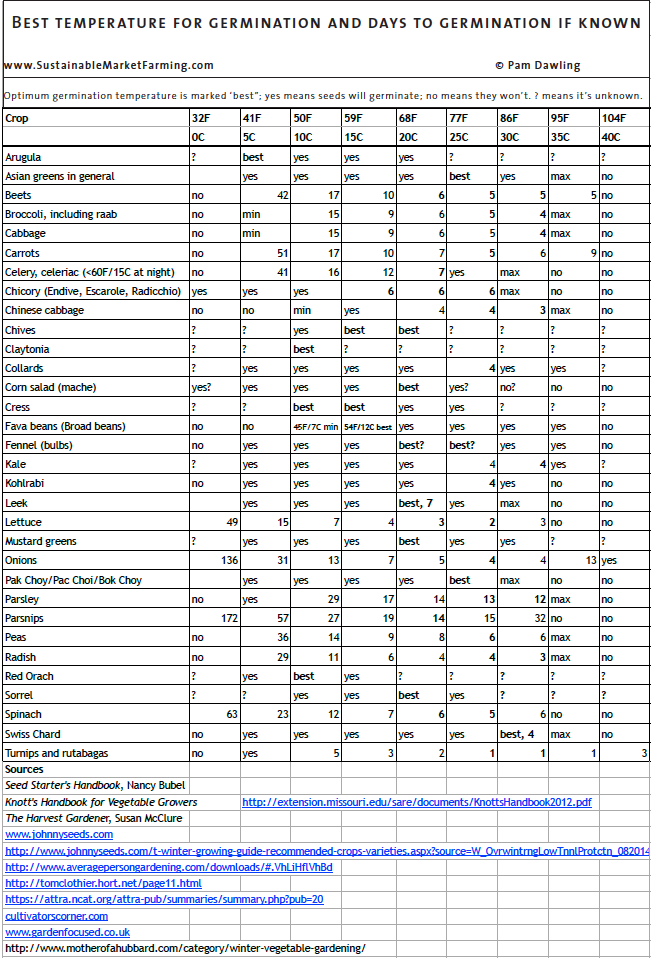

Germination temps

It’s useful to know how many days your chosen crop seeds need to germinate in the conditions you have in your hoophouse in fall and winter. This information isn’t that easy to find. The best sources I know of are Knott’s Handbook for Vegetable Growers (the 2012 edition is now fully online at http://extension.missouri.edu/sare/documents/KnottsHandbook2012.pdf) and Nancy Bubel’s Seed Starter’s Handbook. I have been working to compile a chart, which you can see on the next page. It is a work in progress, so if you have additional (or contradictory!) information, please let me know.

Days to maturity

The ‘Days to maturity’ numbers in seed catalogs are generally for spring planting once conditions have warmed to the usual range for that crop. When planning sowing dates for growing late into the fall, add about 14 days for the slowdown in growth. Secondly, seeds are grown in different parts of the country, and reported days to maturity from a seed supplier in a very different bioregion will not give you an accurate idea of what will happen on your farm. (You can compare that catalog’s days to maturity on something you are familiar with and get a closer estimate that way.) Furthermore, the number usually means ‘Days to First Harvest’ which may not be the same as ‘Days to Full Harvest’. With carrots the exact size doesn’t matter, but an unheaded Chinese cabbage is no good. With CSAs, you could distribute pak choy to some sharers one week and others the next. But if it’s important to have a plentiful harvest when you do start, add another 7-14 days.

Growing Degree Days

These are a measure of heat accumulation and can indicate when crops might be ready to harvest. GDDs can also be used to plan dates for succession sowings. Because GDDs reflect actual conditions, rather than simply the calendar, they provide a method which will work well now that climate change has taken hold and conditions are harder to predict than they used to be.

For most purposes a base temperature of 50°F (10°C) is used – roughly the temperature at which most plant growth changes start to take place. (But spinach, kale and some other greens make growth at 40F.) Each day when the temperature rises above the threshold, growing-degrees accumulate. Record the maximum and minimum temperatures for each 24 hour period, add them, average them and subtract the base temperature. Add each day’s figure to the total for the year to date. This is the simplest GDD figure. Wikipedia has a good explanation and www.farmprogress.com has a free mobile phone app. There is an online Phenology and Degree-day model at http://uspest.org/cgi-bin/ddmodel.us where you choose your nearest site and get current information.

An article explaining the complexities of GDDs is Using Heat Units to Schedule Vegetable Plantings, Predict Harvest Dates and Manage Crops by Nick Andrews and Len Coop, 2011 at http://smallfarms.oregonstate.edu/sfn/f11degreedays

Inspire your guesses

Below: Kale that overwintered in the unheated hoophouse can still be harvested in March. Photo by Wren Vile.

If this is your first year and no-one else in your area grows the crop you want successions of, you can estimate when would be a good planting date to achieve a harvest start date just as the earlier planting is finishing up. Seed companies like Johnnys and High Mowing have suggestions on frequency of sowing of various crops to approximate a continuous supply. johnnyseeds.com/t-succession_planting_methods_for_providing_a_continuous_supply.aspx highmowingseeds.com/blog/top-5-succession-planted-crops-for-extending-the-harvest/ Once you have some harvest information (yours and other growers’), you can gather the data and make a graph. To aim for a really even supply of crops, nothing beats having real information about what actually happened, written at the time it happened!

Collect this information

For each sowing of each crop each year, collect:

1. Sowing date

2. Date of first harvest

3. Date of last worthwhile harvest of that sowing

Compared to spring and summer plantings, the results for winter plantings can look quite whacky. Spinach and kale grow every time the temperature in your hoophouse is 40F (4.5C) or more, but some crops need warmer temperatures to make any growth, and will “sit still” when it’s too cold. Also for some crops the length of the daylight period can make a big difference.

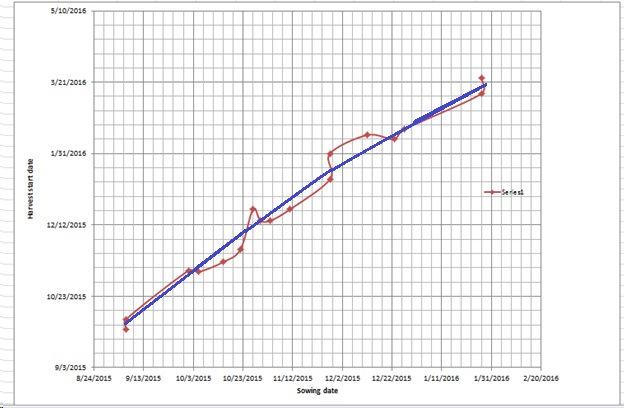

Make a graph (five steps)

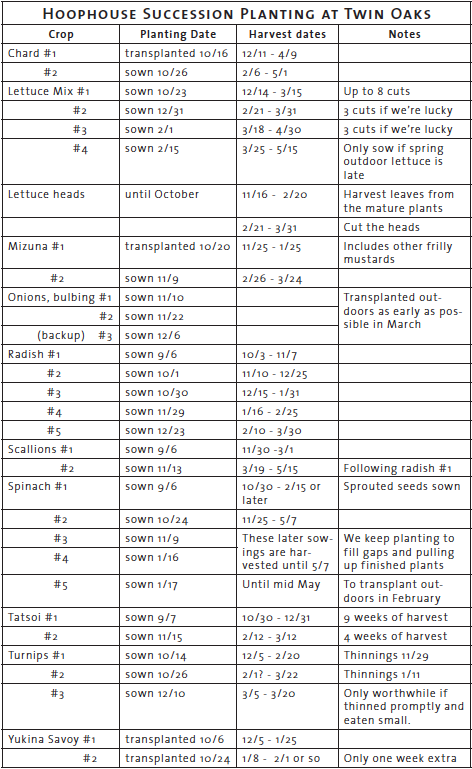

Below: Pam creates graphs for each of her winter crops. Sowing dates are on the horizontal axis and first harvest dates are on the vertical axis.

For each crop, gather several years’ worth of planting and harvesting records in two columns (sowing date and first harvest).

For each crop, gather several years’ worth of planting and harvesting records in two columns (sowing date and first harvest).

1. Plot a graph, with the sowing dates along the horizontal (x) axis and harvest start dates along the vertical (y) axis. Mark in all your data. Graphs can be done by hand or using a spreadsheet program such as Excel, which calls them charts. This type of graph with irregular intervals between entries is called a “scatter chart.” Smooth the extreme jaggedness of the line by drawing a line that has equal numbers of points above and below it, equally distributed over time. See the graph below – with radishes the curve is slight, but it’s there.

2. Mark the first possible sowing date and find the harvest start date for that.

3. Decide the last worthwhile harvest start date, mark that.

4. Then divide the harvest period into a whole number of segments, according to how often you want a new patch. If your hoophouse planting plans exceed the space you’ve got, simply tweaking to a less frequent new harvest start could free up space to grow something else.

5. Use the graph to get the planting dates needed, by drawing a horizontal line from each harvest start date to your graph line, then dropping a vertical line down to the horizontal axis (the planting date). See the example on the next page.

Close successions

Below: A plot of densely sown plants can be transplanted as needed.

There are several advantages to planning close successions.

1. You use all the space to best advantage

2. You may find you don’t need to sow as often or as soon as you had thought, especially if you were verging on over-producing previously. Or you were sowing a crop that wouldn’t even germinate at the prevailing temperatures, and wasting space for a month!

3. The record-keeping may show up some other ways to increase the harvest period (eg pay attention to aphids in February).and remove the need to resow so soon.

4. The record-keeping may show up the chanciness of certain sowing dates, particularly crops that will bolt soon after sowing. See our example of turnips #3 in the Winter Hoophouse Succession Crops Schedule on the previous page. You may decide that planting is less worthwhile than a competing idea.

Information from others

In his new book The Lean Farm, Ben Hartman includes tables from 3 years of growing baby lettuce and spinach. Baby lettuce sown before 22 October was ready to harvest in 5-6 weeks. From 24 October to 16 November the time to harvest increased from 8 weeks to 17 weeks. With spinach the big difference came in the middle of October: before 11 October, spinach took 4-6 weeks to harvest. From 20 October to 1 November, the time to harvest was double or more (12 to 15 weeks).

See page 14 for information about ordering The Lean Farm.

Filler greens

As well as our scheduled plantings, we keep a supply of lettuce, Asian greens and spinach transplants growing and pop a few plants in whenever a gap opens up. Direct sowing of small amounts of fast-growing, small-sized crops such as arugula, mizuna, corn salad, claytonia, cress or tatsoi is a way to make good use of every scrap of space.

Following crops

Sometimes the phrase Succession Planting is taken to refer to the succession of one crop after another. Either way, the goals are to fully use all the space you have and get the maximum possible harvests. We follow our first radishes with our second scallions on 11/17; our first baby brassica salad mix with our fifth radishes on 12/23; some of our first spinach with our second baby lettuce mix on 12/31; our first tatsoi with our fourth spinach sowing on 1/15; our Tokyo bekana on 1/16 with spinach for transplanting outdoors; our pak choy and Chinese cabbage on 1/24 with kale and collards to be transplanted outdoors; our second radishes with our second baby brassica salad mix on 2/1; more of our first spinach with dwarf sugar peas on 2/1; some of our first turnips with our third baby lettuce mix on 2/1. This will give you some ideas of possibilities, although the particulars of crops and dates will depend on your climate.

Pam Dawling manages 3.5 acres of vegetable gardens at Twin Oaks Community in central Virginia. Her book, Sustainable Market Farming: Intensive Vegetable Production on a Few Acres, is widely available, including at www.sustainablemarketfarming.com, or by mail order from Sustainable Market Farming, 138 Twin Oaks Road, Louisa, Virginia 23093. Enclose a check (payable to Twin Oaks) for $40.45 including shipping. Pam’s blog is on her website and also on facebook.com/SustainableMarketFarming. Pam also makes presentations on vegetable growing topics at conferences and fairs from September to May each year.

CORRECTION: In last month’s article about heirloom tomatoes, in the Thumbs Down section, where it says: “Iron Lady: the black stage is immature. The mature stage isn’t very tasty.”

It should have said: “Indigo Rose: the black stage is immature. The mature stage isn’t very tasty.

Iron Lady: Although resistant to late blight and with strong other disease resistance, the flavor and yield were not good enough for us to make the trade off.”

As soon as we start driving our routes in the spring our customers ask us when we’ll have roselilies. They’re that popular and have become a signature crop for us. They’re basically a type of oriental lily, but with multiple layers of petals, and without stamens and pistils (i.e. no pollen!).

As soon as we start driving our routes in the spring our customers ask us when we’ll have roselilies. They’re that popular and have become a signature crop for us. They’re basically a type of oriental lily, but with multiple layers of petals, and without stamens and pistils (i.e. no pollen!).

Prairie Garden Farm has been growing cut flowers for florists and studio designers since 2010. As we’re on an exposed hillside in west-central Minnesota, we’re dependent on protected culture to grow quality flowers. This article describes our approach – planning, financial, and operational details - that helps us make the most of our structures.

Prairie Garden Farm has been growing cut flowers for florists and studio designers since 2010. As we’re on an exposed hillside in west-central Minnesota, we’re dependent on protected culture to grow quality flowers. This article describes our approach – planning, financial, and operational details - that helps us make the most of our structures.