This article appeared in Growing for Market, the national magazine for market farmers published 10 times per year. If you enjoy this article, please explore our website and start a subscription.

In the March issue, I wrote about finding land in the city for an urban farm, and adapting to what is available, affordable, and what seems fitting for the neighborhood and the neighborhood’s needs. Once you have found land that you like, and before you formalize your use of that land, there are several issues you need to settle first.

Zoning

Some farmers approach this zoning issue with the “It’s better to ask forgiveness than to ask permission” philosophy; others do their research and make sure they are legal and operating above board (and some of those who do ask questions regret raising their head above the proverbial horizon). As urban agriculture becomes more commonplace in the U.S., though, there is an argument to be made for behaving in the same way as any other business, which means applying for a permit to do business, complying with zoning laws, and paying your taxes.

It won’t necessarily be easy to find out if your municipality has laws that may restrict or shape your activities; no matter how carefully you explain to the clerk in the zoning department what you are doing, you are almost guaranteed to get a “What is it you want to do again?” and a perplexed look. Here are some of the issues I’ve heard and seen in relationship to zoning:

Agricultural use

Some cities prohibit land inside city limits from being used for agricultural purposes. Sometimes these laws are enforced, sometimes not. Sometimes all it needs is one neighbor complaining about an agricultural activity for the zoning law to be hauled out, dusted off, and applied. Other municipalities consider agriculture the “least use” of land, and so it can be done pretty much anywhere. Talk to zoning and codes enforcement, explain what you are going to do and where, and ask for the applicable codes in writing.

Animal and livestock. Some time ago, U.S. cities began to decide that farm animals didn’t belong inside their boundaries. In some cases, you may find an outright ban on bees, chickens, ducks, geese, goats, hogs, sheep, or cows in the city; in other cases, you might find that set-backs are required (a certain number of linear feet between the animal and the edge of the neighbors’ property) or that the size and number of livestock is limited. Some cities are starting to change those laws; Cleveland just passed an ordinance that makes chickens, ducks, rabbits and bees okay in the city. Their ordinance requires that the resident who wants urban livestock apply for a permit from the Health Department. Start with zoning and codes enforcement to research this.

Home/neighborhood-based businesses

Some cities restrict businesses run from home, both in terms of their capacity to operate and in terms of their ability to promote themselves. For example, one of the farmers we work with sells out of his garage. He can put up a small sign advertising his produce for sale; if the sign gets too big, or multiplies, he then starts encountering official resistance. To run a farm business in a residential zone, you may need to get a special use permit for your farm, which generally requires going to the planning and zoning board and asking permission. You should also see if you need to apply for a business license to operate inside the city limits.

Agricultural structures

Some urban farmers are running into issues with putting in high tunnels or greenhouses. For many of us, high tunnels are allowed because they aren’t considered permanent structures, but that interpretation seems to be increasingly under question. If you want to put in a structure that is larger than some specified square footage, you may also find that you need to go through a building permit process. Consider asking before you put in a high tunnel; or at least be aware that you are avoiding something that may become an issue. (I once got a story in the business section of our local paper on the Growing Growers Training Program I helped to co-found. The next day, I got a phone call from an agent from the State Department of Revenue wanting to know if “my” farmers - the ones who were host farms in Growing Growers - were paying their sales taxes. A single nice photo of your farm and its high tunnel in your daily paper may be enough to bring your structure to the attention of a city official.) There is enormous variation across the country on these issues. When you start your urban farm, some of what you’ll need to decide on the zoning and codes front is “which battles do you want to pick?” If trying to change local laws and codes looks like a good battle, there are an increasing number of communities across the country that are developing more urban-ag friendly codes and their experience and knowledge may be of use to you. You are likely to find allies in the local food movement, in community gardening organizations, and from other community-based movements and organizations.

Water

In some parts of the country, it is possible to farm without regular access to water. It does make your job harder, though, to grow without irrigation and washing water. While a well-established or direct-seeded crop may survive off nature’s rains, it can be harder for newly set-out transplants, and, it can also mean that the process of harvesting and washing off produce can become more challenging.

One option is to pay to get your farm city water service. You’ll need to pay a Tap and Meter Fee to the city water supplier; the cost of that will vary depending on the size of the line you want put in. You’ll need to pay a city-certified plumber to put the meter and line in. If the supply line is across the street, the cost almost immediately becomes prohibitive, you’ll need to pay the plumber and the city to tear up the street to run a line under the road over to your property, which can quickly turn a cheap piece of land into an unprofitable proposition.

If you want to farm on land that is owned by a business or non profit, or someone else’s back yard, you always have the option of purchasing an in-line water meter that will keep track of how many gallons you use, using an exterior faucet, and then paying for your portion of their water bill. Meters can be purchased on-line, we just recently found several that cost under $75. You can also negotiate an agreement to pay a percentage of their water bill based on their previous usage; offer vegetables in exchange for water, or just ask if they would provide water to you because of the service you are providing to the neighborhood.

In some cases, utility companies have been known to put in water service for free or at a reduced cost if the farm site is located in a neighborhood that is struggling and in need of positive community development. If this is to be your approach, make some political connections with the neighborhood association, the city councilor, the mayor’s office, and the board of the utility company.

Security or the ‘neighborhood tax’

There are certain crops that are just going to be difficult to grow in the city, not for reasons of climate, rainfall, or soil quality, but because they are just about irresistible to neighborhood youth, adults, and hungry people. Watermelons top the list, followed, I suspect, by tree fruits. Tomatoes are on the short list, too.

Produce, tools, and equipment can get stolen, and vandalism can happen. Sherri Harvel, whose farm pictures appear with this article, had a pile of manure stolen before she even started growing. The man who took her compost later came by and apologized, saying he thought it was just dumped there. He’d already added it to his own garden but he did pay her something for the manure.

You can approach the question of how to protect your crops and your equipment and supplies in a couple of ways. One is to put a tall fence around your property, which can be effective but can also undermine the whole farming-in-the-city gestalt. Even though it puts up a barrier between your farm and the neighborhood, in some instances this may be a good idea. If you have expensive equipment or vulnerable structures on site - such as sheds with rototillers in them, high tunnels or greenhouses with plastic sheeting, or if the neighborhood is one that just has a high rate of vandalism and theft - a fence may be a more than reasonable choice. The literal and metaphorical barrier the fence puts up can be addressed through hosting pot lucks or public events at the farm, by posting open hours, by inviting local groups to tour the site at specific times and dates or finding other ways to make it clear to the community that you welcome their involvement and presence.

Another approach is to put a shorter fence around the property- even something as simple as chicken wire and t-posts can create a bit of a safety zone for your farm. Another security measure is the neighbors. If they know you, understand that you are trying to improve the neighborhood and do something positive, they are more likely to keep an eye out for troublemakers. Give them your cell phone number, and drop off extra veggies when you can. Another solution is to set aside extra produce with a sign “Help Yourself” outside of your fence, in the shade. Or put up signs saying “Please respect the garden and the hard work we put into it! If you’d like some of our produce, you can buy it at…”

Farms in the city require a willingness to engage with neighbors, with municipalities, and with other businesses and stakeholders. It won’t always be easy — not everyone thinks that a city farm is a positive use of open land in the city. But as food prices and diet-related diseases and food contamination issues continue to be problems, more and more urban communities are adapting their policies and practices to support neighborhood-based food production.

Katherine Kelly is Executive Director/Farmer of the Kansas City Center for Urban Agriculture. She can be reached at [email protected]. She enjoys hearing from other urban farmers and welcomes suggestions for future articles on urban farming.

I own and operate Bluma Flower Farm, currently located on a rooftop in downtown Berkeley, California. Going into this year my plan was to try to replicate what I did the year before, one of Bluma’s best years yet. This would have been the first year I didn’t make any big changes. But then the pandemic hit and, of course, like many other businesses, I had to pivot and find ways to survive.

I own and operate Bluma Flower Farm, currently located on a rooftop in downtown Berkeley, California. Going into this year my plan was to try to replicate what I did the year before, one of Bluma’s best years yet. This would have been the first year I didn’t make any big changes. But then the pandemic hit and, of course, like many other businesses, I had to pivot and find ways to survive.

Until two years ago I was germinating all seedlings in greenhouses using almost exclusively bottom heat from electric heat mats. At my current farm we only had space for about 8-10 trays on our two mats and we definitely noticed differences in the germination (and presumably the heat the mats were providing) on the edges of our trays.

Until two years ago I was germinating all seedlings in greenhouses using almost exclusively bottom heat from electric heat mats. At my current farm we only had space for about 8-10 trays on our two mats and we definitely noticed differences in the germination (and presumably the heat the mats were providing) on the edges of our trays.

Sarah Nixon compulsively grew flowers in her Toronto backyard and filled her house with blooms. Then, she moved on to her neighbors’ yards. Thus was born My Luscious Backyard, her floral business, an urban flower farm created with a network of back and front yards. Today, her neighbors in Toronto’s Parkdale neighborhood are accustomed to seeing her station wagon loaded with buckets of flowers that find their way to florists, subscription clients and weddings.

Sarah Nixon compulsively grew flowers in her Toronto backyard and filled her house with blooms. Then, she moved on to her neighbors’ yards. Thus was born My Luscious Backyard, her floral business, an urban flower farm created with a network of back and front yards. Today, her neighbors in Toronto’s Parkdale neighborhood are accustomed to seeing her station wagon loaded with buckets of flowers that find their way to florists, subscription clients and weddings.

Dogpatch Urban Gardens (DUG) is an urban farm located in Des Moines, Iowa, owned by Jenny & Eric Quiner. The farm slogan is, “Cultivating Community,” and in the two seasons of business the community support towards the farm has been monumental. 95% of the produce is sold within 10 miles of the farm. The main avenue for sales is the on-site DUG FarmStand. The stand sells crops grown on site, and also resells items from other local growers & producers. Think of the stand as a locally sourced grocery store.

Dogpatch Urban Gardens (DUG) is an urban farm located in Des Moines, Iowa, owned by Jenny & Eric Quiner. The farm slogan is, “Cultivating Community,” and in the two seasons of business the community support towards the farm has been monumental. 95% of the produce is sold within 10 miles of the farm. The main avenue for sales is the on-site DUG FarmStand. The stand sells crops grown on site, and also resells items from other local growers & producers. Think of the stand as a locally sourced grocery store.

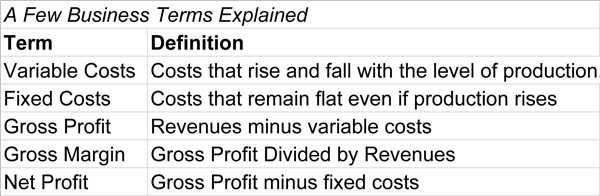

As I write this in December, the planning season is beginning in earnest. My wife and I have begun poring over our records from this past season. We’re tallying yields and plantings, adding up labor, and trying to make sense of the hastily scribbled notes in the margins of our records that we so urgently wanted our future selves to remember so we wouldn’t make the same mistakes again. Soon we’ll begin our winter planning meetings with our customers. Hopefully out of that process will emerge a production plan that theoretically enables us to pay our expenses and ourselves - provided we can enact it with only the usual amount of unpredicted surprises.

As I write this in December, the planning season is beginning in earnest. My wife and I have begun poring over our records from this past season. We’re tallying yields and plantings, adding up labor, and trying to make sense of the hastily scribbled notes in the margins of our records that we so urgently wanted our future selves to remember so we wouldn’t make the same mistakes again. Soon we’ll begin our winter planning meetings with our customers. Hopefully out of that process will emerge a production plan that theoretically enables us to pay our expenses and ourselves - provided we can enact it with only the usual amount of unpredicted surprises.