By Jed Beach

As I write this in December, the planning season is beginning in earnest. My wife and I have begun poring over our records from this past season. We’re tallying yields and plantings, adding up labor, and trying to make sense of the hastily scribbled notes in the margins of our records that we so urgently wanted our future selves to remember so we wouldn’t make the same mistakes again. Soon we’ll begin our winter planning meetings with our customers. Hopefully out of that process will emerge a production plan that theoretically enables us to pay our expenses and ourselves - provided we can enact it with only the usual amount of unpredicted surprises.

It’s a season of spreadsheets, QuickBooks reports, customer conversations, and lots and lots of details regarding crop performance, sales, expenses, profits, and margins. While these details are important, it is also important not to lose sight of some of the big picture goals that will enable you to define, plan, measure, and achieve a successful year farming.

Awhile back, the editor of this magazine asked me to write an article entitled, “Common Financial Mistakes Farmers Make.” In this article, I’ll describe five of the most common ones I’ve seen in myself as a farmer and in the farms I’ve worked with as a business counselor.

I present this list with a few caveats:

This list is by no means comprehensive.

While these mistakes are (by my estimation) common, they are not necessarily applicable to all, or even most farmers out there. I’ve had the privilege of working with growers who have devised ingenious solutions to each mistake listed here-and I’ve also tried to share a condensed review of solutions to each common mistake. If reading this causes you to become aware of how you’ve made at least one of these mistakes, and gives you some possible solutions, then it has done some good.

#1 Not paying yourself

Try this exercise: imagine your farm losing one of its critical assets overnight. What would you do? Would your farm be able to survive, say, the loss of one of its tractors? A greenhouse? An employee? Most likely, the loss of any of these things would be a blow - but you could recover. You’d find replacements, have backup plans. But what if you disappeared overnight? More often than not, the farm would cease to effectively operate.

The most critical cost on your entire farm is the “Cost of You,” the farmer - and far too often, it’s also the most underpaid and exploited cost as well. I’ve regularly visited farmers who put in 70-80 hour weeks during the growing season, only to draw little more than poverty-level wages from their farm. You wouldn’t dream of not paying your tractor repair bill, or your employees. You probably put them into your budget. Why not do the same for yourself?

There are a couple simple solutions to this problem. First, you have to decide “How much do I need to pay myself from my farm each year?” It may be helpful to calculate your non-farm cash flow to answer this; add up all your personal expenses, as well as contributions you might like to make to retirement, savings, college fund, etc., then deduct any off-farm income from this total. The resulting sum is the minimum amount you need to pay yourself from your farm; aka “The Cost of You.”

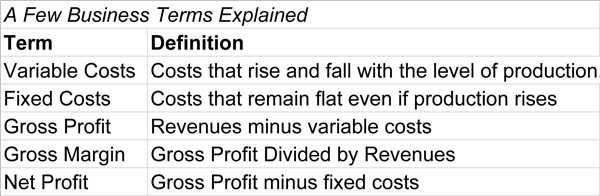

Next, write yourself in as an expense on your upcoming farm budget. The easiest thing to do is to insert the Cost of You into your expense budget as a fixed cost, right between insurance, depreciation, etc. To be more accurate, you would ideally split the Cost of You into fixed and variable costs; the time you spent alongside your employees engaged in direct production should be variable, while the time you spend doing “everything else” should be fixed. For a detailed description of fixed vs. variable costs, gross vs. net profits, and gross margins, see my article in the March 2016 issue of Growing for Market; I’ve compiled a brief sidebar here to quickly familiarize you.

Now, check the bottom line (net profit) on your budget. Is it $0 or above? If so, great! You’re able to pay yourself adequately.

If not, you’ll need to either grow your sales (get bigger), or increase your gross margin (get better). To find out just how big you might need to grow, divide your fixed costs (including the “fixed” portion of the Cost of You) by your gross margin - that’s the level of sales you’ll need to reach.

One thing is nearly certain - if you don’t plan to pay yourself, you almost certainly won’t.

#1(b) Not paying yourself for your “office and shop time.”

This is a closely related subset of Mistake #1. When you are calculating the Cost of You, make sure you’re not just thinking of your time spent in the field or pack house, such as weeding, planting, harvesting, etc. In business-speak, this is often called, “direct labor.”

“Indirect” labor refers to any work not directly involved in production - this includes bookkeeping, repairing equipment and buildings, communicating with customers, filing paperwork, reading articles by people telling you that you should pay yourself adequately, etc. I sometimes call indirect labor, “office and shop time.” Indirect labor is often a substantial portion of a farmer’s time, especially as the farm gets larger. It’s important to value it and make sure your farm pays you for it - otherwise, you’ll find (as many have) that you’ll be taking care of these tasks during evenings, Sundays, or other supposed “free” time. That gets old. Better to make sure the business covers the cost of your office and shop time, and hire someone to shoulder a larger burden of the direct labor so you can work a relatively sane schedule.

#2 Assuming that, in order to pay yourself more, you have to grow the size of the business.

It often happens that a farmer believes he or she needs to continue growing in order to be profitable, and to be frustrated by the results of that growth. The farm often starts out as a small, diversified business operated mostly by the farmer (or farmers). As the farmers grow their farm - say, from 2 acres, to 4, to 8, to 10 - they simply increase the quantity of everything they are already doing - and maybe add new enterprises as well. After a certain point, they hit a “wall” of sorts, where they are working harder and harder, but actually making less money. Farms that move beyond this “wall” usually do so by reducing their operations - by cutting crops, growing on less acreage, or cutting staff.

At the end of Mistake #1, I described a method for estimating the level of sales growth you would need in order to pay yourself adequately. While growth is one option, many farms equate growth with profitability - that is, they assume that they have to increase the size of their businesses in order to make more money. Often, this is not the case. There are usually ways for a farm to increase its efficiency - that is, the ratio of revenues to expenses - so that it doesn’t have to grow (or grow as much). In effect, this means reducing expenses while maintaining the same level of income - and thus increasing net profit.

Some common ways to increase efficiency include:

Focusing on most profitable crops

More accurately matching production to sales

Ensuring yields are at or near their optimal rates

Investing in equipment that reduces labor cost (more on that later).

The best way to measure efficiency is to look at your gross margin (see sidebar for definition). An FSA loan officer once told me that, as a general rule of thumb, if a farm’s gross margin is at least 50%, they consider that healthy, and growth is the better option for increasing profit. If the gross margin is lower than 50%, they encourage the farm to look for ways to get more efficient first. As I have implemented this rule, I have generally found it to be accurate.

#3 Growing crops just because you can sell them (without any sense of your profitability).

Most farms I work with make some effort to match their production to suit their customer’s demand for it. They usually contact their customers in the winter (or review their farmer’s market logs), and ask something along the lines of, “What can I grow for you next year?” There’s nothing wrong in gathering such data; in fact, I encourage it. What’s problematic is when the farmer agrees to grow and sell something “just to make the sale”; that is, without any idea of whether or not they will turn a profit at the price offered.

This is a mistake I see most often amongst farms in a market environment that’s becoming increasingly competitive. Existing farms have usually taken up the more profitable “low hanging fruit”, and newer farms are anxious to accept any deal that they believe will help them gain a foothold in the marketplace.

Believe it or not, many buyers actually don’t like it when they discuss pricing with a farmer, and he or she says something along the lines of, “Just tell me what you can afford to pay.” Most buyers - especially those committed to building a local foods system - see themselves as partners with farmers, and they want to make sure they’re paying their farms a price that’s sustainable for all parties. If the farmer doesn’t know what that price is, it raises questions in the buyer’s mind - “How do I know if this person will still be around in 2 years? Is this a relationship I want to invest my time in?”

I have one colleague who works for a distributor, who informs me she has stopped working with new farms who can’t answer the, “what price do you need for your farm?” question.

#4 Not knowing your unit costs

This mistake goes hand in hand with mistake #3. “Unit cost” is defined as, “your cost to produce one lb. of carrots (or gallon of milk, bushel of apples, etc.).” It is calculated by dividing all of the costs associated with a particular crop by the yields of that crop.

Different people sometimes use unit cost differently. Some people calculate “variable unit cost,” which is all the direct variable costs of a crop divided by yield. I prefer to use, “fully loaded unit cost,” which includes not only variable costs, but also all fixed costs including the Cost of You. Another way of defining unit cost is, “The price you need to receive in order to pay all your expenses and yourself.” It is very useful to have this price in hand before agreeing to grow anything for any customer!

If my farm grew nothing but beets, and sold them by the lb., calculating unit cost would be simple - I would take all my expenses, including the Cost of Me, and divide them by the number of pounds of beets I harvested. Done!

But for a highly diversified farm, calculating unit cost is a deceptively simple concept that can prove to be a bit of a rabbit hole. If I grow beets plus 49 other crops, I have to untangle which expenses are associated with which crop in order to calculate unit cost.

Explaining some methods for doing so is another article unto itself. However, here is a rough and ready method that will work for a diversified crop farm that doesn’t have much in the way of specialized, crop-specific equipment:

Build an enterprise budget focused on the variable costs for a specified area of measurement (“It takes a crew of 2 people 1 hour to plant 100 bedfeet @ $12/hour = $24 labor cost”. “We also apply 2 cups fish emulsion per 100 bedfeet @ $1 per cup = $2”, etc.)

Add up your total direct variable costs per your area (Total Variable costs = $26 per 100 bedfeet”)

Add up your total fixed costs (including the fixed portion of the Cost of You), and divide them by the total annual planted bedfeet on your farm (We have a total of $10,000 fixed costs, and 10,000 planted bedfeet, so that’s $1/bedfoot or $100 per 100 bedfeet)

Add these to the variable costs ($26+$100=$126 per 100 bedfeet)

Divide this by the yield of that crop per unit of area ($126 divided by a yield of 63 bunches per every 100 bedfeet equals $2 per bunch unit cost).

#5 Undercapitalizing yourself

Partly because they don’t value the true cost of their own time, many growers I work with don’t invest in equipment that may actually make their production more efficient. Often, they don’t do so because they perceive the initial price tag to be too high. Rather than looking at the labor-saving value the equipment provides over time and depreciating that purchase cost over a period of many years in their minds, they react to the initial sticker price.

A simple method for evaluating when a piece of equipment is “worth it:”

Calculate an enterprise budget (see above) for your production without that equipment; calculate your variable unit cost, gross profit, and gross margin.

Now, do the same with the piece of equipment.

Compare the difference in gross margins.

Now divide the equipment’s annual operating cost (usually depreciation, fuel, and maintenance) by this difference in gross margin. That’s the level of sales you’ll need in order to make the equipment purchase “worth it.”

When I run this calculation with growers, we often find that the sales threshold needed to justify a purchase is much lower than expected. For instance, I’ve worked with growers who’ve made relatively expensive investments ($15-$20K) in mechanical harvesters for various crops; these growers report being more efficient than their previous hand-labor methods at five or more acres of any given crop. (Please make sure you run the numbers for yourself before deciding to invest in equipment. The price tags and acreage I quote here are for rough guidance only).

So in conclusion, if you:

Build next year’s expense budget to include the Cost of You, including your “office and shop time,”

Calculate your unit costs for your major products,

Only agree to grow crops at prices that are at or above your unit costs;

Consider options for getting more efficient before considering growth; and

Invest smartly in equipment that saves on labor cost;

You’ll have a great foundation for a successful farming year!

Jed Beach is a farm business consultant and organic vegetable farmer in Lincolnville, Maine. He and his wife operate 3 Bug Farm, where they wholesale greens, herbs and other crops to stores and restaurants. Jed provides business planning services and crop profitability assessments to farmers through his practice, FarmSmart. More information can be found at www.farmsmartmaine.com.

Flexible business planning to evaluate new farm enterprises

Flexible business planning to evaluate new farm enterprises Close your eyes; think about your last trip to visit an accountant. Did you have an awful feeling in the pit of your stomach? Maybe you remembered the growing stack of invoices on your dining room table, or talking about money makes you uncomfortable. Visiting an accountant can feel like a dreaded dentist appointment, but it doesn’t need to and remember it’s an important aspect of a successful farm business.

Close your eyes; think about your last trip to visit an accountant. Did you have an awful feeling in the pit of your stomach? Maybe you remembered the growing stack of invoices on your dining room table, or talking about money makes you uncomfortable. Visiting an accountant can feel like a dreaded dentist appointment, but it doesn’t need to and remember it’s an important aspect of a successful farm business.

I own and operate Bluma Flower Farm, currently located on a rooftop in downtown Berkeley, California. Going into this year my plan was to try to replicate what I did the year before, one of Bluma’s best years yet. This would have been the first year I didn’t make any big changes. But then the pandemic hit and, of course, like many other businesses, I had to pivot and find ways to survive.

I own and operate Bluma Flower Farm, currently located on a rooftop in downtown Berkeley, California. Going into this year my plan was to try to replicate what I did the year before, one of Bluma’s best years yet. This would have been the first year I didn’t make any big changes. But then the pandemic hit and, of course, like many other businesses, I had to pivot and find ways to survive.