I began Neversink Farm six years ago. Building the farm that first year was incredibly hard work, but it was that early experience of struggle that shaped the foundations of how I would farm going forward. My wife and I managed to pull together $30K. With that, a dream, a lot of enthusiasm and not much else, we said goodbye to city life.

We leased a beautiful piece of land just a few hundred yards up the river from a cabin I had purchased years ago. The land had more rocks than dirt, no water, a barn and loads of quackgrass. Our initial purchases for the farm that first year were a small propagation house to start seedlings, a small simple hoop house in which to grow tomatoes, and a two-wheel tractor to till and plow the fields. We had a great desire to farm but lacked experience and knowledge in the craft.

We wanted to stay very small, but we also wanted to live well. We were not young and since we had no retirement money, we concluded, however naively, that to live well, have kids, and be able to retire at some point, we should try to make at least $400K gross within a few years, and we would expand to whatever amount of acreage that demanded. We were obviously not yet schooled in small scale farming financials, because if we were, we might never have left the city with that kind of goal.

We began our farm adventure with a lot tilling. Turning a field of grass and weeds into a productive farm can seem like an impossible task. It can be the hardest part, physically, of starting a new farm with or without a tractor. This is where putting the hard work in at the beginning really pays off more than anywhere else on the farm, especially if you choose not to till.

I looked out over our field after we signed our first lease and imagined neat rows of perfect and identical vegetables, where every row is straight and true interrupted only by even more perfect grass paths where handcarts would be rolling around overflowing with produce. In my mental image there wasn’t a weed, diseased plant or pest anywhere, but I had no idea how to get there. I concluded that tilling everything in with a walk behind tractor was the obvious choice. I didn’t consider any other course of action.

Much of our startup capital was spent on that BCS walk behind, and it was that horsepower that gave me confidence. From sunup to well past sundown, I would till and plow, the tractor bouncing wildly over the river stones. My wife Kate would run alongside to grab the rocks and put them in a cart that we would haul together hundreds of yards to the woods. We made hundreds of trips.

Below, putting the work in up front by removing rocks from beds.

This went on for week after grueling week, tilling sections over and over to try and break up the mounds of grass but they wouldn’t disappear. These clods of perennial grass roots would get in the way of everything we did, making us curse as we tried to lay out my imagined straight rows. Planting was torture, as I would hit clumps of grass with the trowel. Forget about using a seeder under these conditions.

In desperation I used plastic mulch in some of the worst areas to try and tame the grass that was emerging at a really scary rate after spring rains. One could not tell where the grass paths ended and our production beds began. There is no way to earn money this way, we thought. What are we doing? We felt Neversink may be sunk. But if either of us seriously felt like giving in, the other would feign confidence that we would figure this out and be successful. We lifted each other up and focused on getting any vegetables we could out of the weed jungle and getting them sold. From that tiny first field of weeds we did earn a small profit, but only because of our free labor. I felt like a failure at farming but we wouldn’t give up.

Well that was it. There would be no more weeds at Neversink Farm. That next season, we decided to get on our knees and pull out every weed, inch by inch, foot by root, row by back breaking row until all, and I mean all, the perennial weeds and their roots were gone. Our fingers would bleed, but we were not going through the horror of last season. We were going to put the hard work in up front to make farming easier going forward and this would become a cornerstone of how we farm.

On a daily basis I seek ways of making farming easier. If we could make a huge sacrifice for our future selves and for our farm then we would. Whether it was really hard work or purchasing a piece of equipment that we could not afford, if it resulted in simplicity and efficiency, we would do it, because that will ultimately lead to easy, enjoyable farming and profitability. In farming, simplicity can be achieved by stripping away complexity but can also come from investment either financially or through hard work. The hard work of removing all the weeds made everything simpler and easier for years to come.

We had only tamed one small field of perhaps a half an acre and we knew that we needed to grow, but creating new fields by tilling was not going to happen. Pulling a new pasture out by hand would have sent us back to the city, screaming. This time we looked for a simpler and cheaper method. Solarization was where we turned. This is usually done with clear plastic to heat soils up to reduce pests and disease, as well as kill weeds.

Our farm is in zone 5a, so when we used clear plastic, it acted more like a greenhouse in early spring and while some weeds were killed others thrived. We abandoned clear plastic and used black. Solarization is time and temperature dependent. You can have a lower temperature under black plastic, but it will need to remain in place longer. A weed seed will cook when flame weeded at scorching high temperatures and be killed in seconds. Lower temperatures for a prolonged period of time will do the trick as well, but that time must be increased drastically. A few seconds turn into months. Since we had the time, this method was perfect.

Below, how Neversink Farm looks today.

That spring, I spread a large piece of black plastic on top of a new section of virgin field. The plastic was removed the next spring and underneath was bare soil with no weeds or viable roots. It was amazing. I continued to reuse that piece of plastic, which is the same size as one of our field sections, by sliding it from a finished section over to a new section each season to open up new ground. We were ecstatic at how well it worked. We laid out rows, forked and began planting. The perennial weeds never came back and for a no till system to be highly productive, it must be free of all perennial weeds. It was that hard work in the first season that solidified my policy of seeking easy solutions wherever possible.

Tilling is generally done at least once a season over the entire farm and then after every turnover of crops. Before tilling, irrigation and anything else in the field must be removed. After tilling, the beds then need to be laid out again and the irrigation brought back in. To be ultra-efficient those beds need to be measured precisely, and made straight so that no space is wasted. The footpaths also must be marked out in some way so they are clearly visible. After all of this hard work, you then need to do it all over again next season. On top of that, weed seeds are being brought to the surface and the soil is getting overworked. Thus tilling also has the side effect of increasing the amount of required cultivation and soil amending. Never tilling again was an easy choice, so I just stopped. I never wanted to be in the weeds again.

Neversink was suddenly a no-till farm. The tiller and the two-wheel tractor, I came to realize, were unnecessary, really hard work, time consuming, and added too much complexity to our systems. There would be no tilling done from here on out and the time consuming task of laying out rows would be done once. All of our beds are now permanent. The beds are staked and the rows never change size, and they are ready as soon as the snow melts. The bed stakes are there waiting for us to attach guide string for our seeding and planting. The irrigation can be left in place, avoiding the task of dragging it out from the barn each spring.

Below, permanently staked beds. All photos courtesy of Conor Crickmore.

Each permanent bed has been assigned a unique ID and I created easy to read maps that I use to assign tasks to specific highlighted beds. What could be a more permanent and simple solution on the small-scale farm? One of the biggest misconceptions of no-till farming is that we must be breaking our backs. I think people picture me strapping plows to my workers like draft horses. I stopped tilling or using the two-wheel tractor because it is much easier, more efficient, simpler and more profitable for us. It has made farming at Neversink very enjoyable. It was the best efficiency improvement we made.

Once we were on the road to efficiency, I wanted to maximize it. Thus my goal is to have every square inch of our 1.5 acres producing to its potential and producing all the time. To achieve this, any bed that is harvested in the morning, I want replanted by the afternoon. This is done across the farm. Because we don’t have to clear large areas to get a tractor into, we have the luxury of being able to replant or reseed any sized area.

Below, scallions harvested in the morning were replanted later the same day.

The permanent beds are prepared or turned over with four easy steps. First, vegetable matter is removed though roots of some crops remain. Depending on the crop this initial step can be done a few different ways and I have put much thought into efficiency improvements for this step. Second, the bed is deeply broadforked. In a field of rocks this can be really hard, but we already put the work in and cleared out any rocks so that forking is a very pleasant activity. Third, the bed is amended and conditioned depending on that bed’s needs. Last, I use a Tilther.

The Tilther is my power tool of choice. It is light, simple, and does the job. It disturbs only the top inch of soil and works in the amendments and smooths the bed. I can throw the Tilther over my shoulder and carry it around the farm. It is great in winter since it produces no exhaust to poison me while using it in the greenhouse. My four-year-old can walk alongside me while I use it. They are cheap, so I can have them at easy-to-grab locations around the farm. The Tilther is the elegant simple solution for “Neversink No-Till” farming.

After a couple of seasons of dialing in what we now call “Neversink No-Till” systems, the field started to look as neat and productive as I had imagined it that first year. There were straight rows, no weeds, and healthy uniform vegetables. I no longer felt like I failed at farming but that I had found a way I could be very successful through simple solutions. I don’t want to work harder than necessary. That is why I spend a lot of my time looking for the easy and simple solutions. Farming is my dream job and building it is a joy, but the work I love most is the work that results in less work. Farming can be and is extremely complicated. Thus, I enjoy watching my farm move towards successful simplicity.

Below, the tilther is used anytime, anywhere and with a four-year-old.

Using no-till practices that were developed at Neversink along with the important lessons learned early on, we quickly grew the farm over the following years. The farm grew mostly in production but not in size. These important lessons were to never add more work but rather to reduce it. Use permanent solutions and keep things simple while investing in infrastructure and new systems. Field sprinklers are a great example of the results these lessons. They are a large infrastructure investment. In a no-till system they can be left there permanently and unlike drip, sprinklers irrigate beds evenly and quickly which increases the germination rate of seeds and the survival of seedlings. Drip can be time consuming to manage while our sprinkler system is almost no maintenance. Also sprinklers are not in the way when cultivating as drip can be. When I want water, I only need to lift the handle of the hydrant.

When deciding on an improvement to the farm, I not only ask, “will this improve production?” but I also want to know if it will increase work. A good example of where we implemented the lesson of not adding work is in high tunnel design. At the beginning we used caterpillar tunnels since they were cheap. While they do increase production slightly, they also brought with them a lot of problems, and a lot of work. They need a lot of attention and only made sense when we wanted to grow our production regardless of the resulting work. We quickly abandoned caterpillar tunnels and moved towards more high-tech, better-built structures that require almost no attention. These structures increase production dramatically. I’d rather have one great no-maintenance tunnel than ten cheap ones. It is better to have beautiful healthy production on one bed than not-so-great production on many. With a better tunnel, I can do more with less. This philosophy is also why we do not use row cover and low tunnels in the field. Their promise of increased production comes with a lot of work as well.

I also found that field plastic adds work and problems. While we did use plastic to open up new fields, we really try to avoid using it or landscape fabric on production beds or next to hoop houses. Voles and mice love it. Instead I put the work in up front to reduce the need for plastic by removing weeds, and building permanent gravel trenches alongside tunnels.

Stripping down our record keeping to the bare essentials was a huge time saver. I started with very complex spreadsheets for everything around the farm and now have what I call “cheat sheets” that give me all the information on one page. My entire year’s planting schedule is on one small laminated card. I have simple task tickets to direct employees in their work. I do not keep elaborate records of everything harvested, planted, and sold.

Rather I use an easy “check-in” process to see if a crop or method is profitable. I randomly take a look at a whole system, like the lifecycle of a box of carrots from planting to market to see if carrots are earning money and how much. By doing this intermittently or after an improvement, I can see if we are earning profit, or if a system is getting worse or improving. I do not need to check every box of carrots but only one or two boxes every couple months. If I am duplicating a profitable process, then I know every box of carrots is profitable. Cheat sheets and check-ins are so easy, so simple and a lot less work.

Below, no-till in the hoophouse.

After reading books on soil, I was just getting more confused, so simplifying it was the only way for me to make sense of it. Soil fertility can be an extremely complicated subject and while I wouldn’t claim that the vast knowledge in that field is unnecessary, I do feel that for me I needed to break it down. I simplified my soil building program to three simple steps. The first being pH and calcium balancing which is only done every two years and I keep careful records on this. The second step is soil conditioning which is based only on the feel of the soil. The last, which is done regularly, is fertilizing and is based on soil tests and crop needs.

All of these changes had the cumulative effect of leaving me vastly more time, which I spent managing rather than working the farm; the more time I spent managing the systems the better the farm did. Our numbers started climbing rapidly and as a result I could invest in more small and large improvements. I could monitor our systems for bottlenecks- places where production is squeezed and thus slowed down. I could also slowly organize and systematize many areas of the farm that I had ignored previously. We thought we would need at least four or five acres in production to reach our early revenue goals but our production climbed much faster than our need to expand acreage. By year five, we were able to come very close to our early goal of 400K on just 1.5 acres. I now feel that for us 1.5 acres is the comfortable limit if we wish to maintain a healthy production to profit ratio while also having a limited staff and working reasonable hours.

Our farming start was extremely hard, much harder than it needed to be. But it was through that experience that I was able to develop our no-till systems, our simple solutions and our emphasis on reduced work. We suffered due to our inexperience, but we learned fast and we continued to master our own stripped down and efficient system of farming. It was the suffering that taught us to change and not to be stuck to any one way of doing things and to design every process with simplicity and elegance. I learned to avoid adding more work for small production gains. That early hard work also taught me to put the work in up front if it resulted in less work going forward. We were able to turn failure into an incredibly productive and successful farm.

The number of small farms is rapidly rising. This is a great thing. There is a small farm revolution happening and I now have time to help other farms hopefully avoid the mistakes we made. I exchange information with other farmers through our social media, during our on farm courses, and my consulting work. I know we can do better together and sharing knowledge is the best way for us all to get to easy, enjoyable, profitable farming.

This is the first in an occasional series of articles on Neversink no-till systems.

Conor Crickmore is a farmer and small farm consultant who lives and works in the Catskill Mountains of New York. For more information see his website: www.neversinkfarm.com Instagram: @neversinkfarm Facebook: neversinkfarm

/

/

In recent years a great deal of interest has been building around the question of how to run a profitable, chemical-free farm without tillage. We all know what tillage does to soil, but the available information about how not to till on a commercial market garden scale has felt impractical or unusable, much of it geared towards home gardeners or mega grain operations in chemical monoculture. There has been, to be sure, very little in the way of guidance on how to approach a profitable, diversified no-till farm.

In recent years a great deal of interest has been building around the question of how to run a profitable, chemical-free farm without tillage. We all know what tillage does to soil, but the available information about how not to till on a commercial market garden scale has felt impractical or unusable, much of it geared towards home gardeners or mega grain operations in chemical monoculture. There has been, to be sure, very little in the way of guidance on how to approach a profitable, diversified no-till farm.

If you’ve been a subscriber to Growing For Market (or even if you haven’t), you’re probably familiar with the many advantages of no-till agriculture. No-till methods can reduce a farm’s carbon footprint, promote complex soil biology, and preserve and build organic matter.

If you’ve been a subscriber to Growing For Market (or even if you haven’t), you’re probably familiar with the many advantages of no-till agriculture. No-till methods can reduce a farm’s carbon footprint, promote complex soil biology, and preserve and build organic matter.

In the mid-1980s I had a farm in upstate New York and grew 20 acres of organic vegetables with machinery. It was organic, but not sustainable both for the use of fossil fuel and high level of personal burnout. I lost my joy of farming and never thought I would go back into it for my livelihood.

In the mid-1980s I had a farm in upstate New York and grew 20 acres of organic vegetables with machinery. It was organic, but not sustainable both for the use of fossil fuel and high level of personal burnout. I lost my joy of farming and never thought I would go back into it for my livelihood.

This month’s submission is from Dogpatch Urban Gardens in Iowa and it’s a simple one – a grabber being used to reach Tomahooks obviating the need for a ladder. It’s quite possible that many of you have already thought of this, but I had never seen this before. I love the idea and I don’t even use hooks…but I might after seeing this.

This month’s submission is from Dogpatch Urban Gardens in Iowa and it’s a simple one – a grabber being used to reach Tomahooks obviating the need for a ladder. It’s quite possible that many of you have already thought of this, but I had never seen this before. I love the idea and I don’t even use hooks…but I might after seeing this.

Like all of you, I’m always trying to make little improvements around the farm, and I’m never finding enough time to try all of my ideas. Last year I had the opportunity to rebuild the packing area at Cully Neighborhood Farm (CNF) and to also build three prototype pieces of furniture for a new packing shed at the North Willamette Research and Education Center (NWREC) for their small demonstration farm and to try out some of my ideas.

Like all of you, I’m always trying to make little improvements around the farm, and I’m never finding enough time to try all of my ideas. Last year I had the opportunity to rebuild the packing area at Cully Neighborhood Farm (CNF) and to also build three prototype pieces of furniture for a new packing shed at the North Willamette Research and Education Center (NWREC) for their small demonstration farm and to try out some of my ideas.

We regularly harvest into a half dozen containers on our farm. Bulb crates, flip-top crates, storage crates, pallet bins, five gallon buckets, and waxed boxes. Our new favorite receptacle, though, is vastly more ergonomic and hands-free, and has changed the way we pick several crops, making it faster and more efficient and enjoyable.

We regularly harvest into a half dozen containers on our farm. Bulb crates, flip-top crates, storage crates, pallet bins, five gallon buckets, and waxed boxes. Our new favorite receptacle, though, is vastly more ergonomic and hands-free, and has changed the way we pick several crops, making it faster and more efficient and enjoyable.

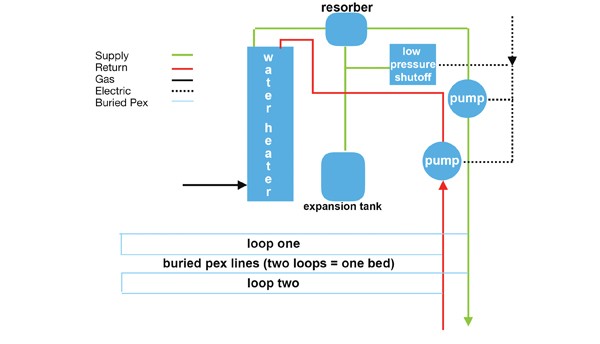

Do you want to be able to heat your greenhouse with radiant heat? Are you interested in being able to heat your soil to extend your season or even grow through the winter? In this article we will examine how we built a hydronic radiant heat system for our greenhouse, and how you can do this at your farm.

Do you want to be able to heat your greenhouse with radiant heat? Are you interested in being able to heat your soil to extend your season or even grow through the winter? In this article we will examine how we built a hydronic radiant heat system for our greenhouse, and how you can do this at your farm.

A mile of gravel road crosses the Winooski River over an old covered bridge, leading to Cate Farm. On a beautiful clear bright summer day, the long and lanky Richard Wiswall saunters over to warmly welcome me. Even though it’s a Monday morning in July in Vermont, during what should be the busy season, he’s full of smiles and exudes warmth and ease. Instead of a stressed-out, disheveled grower, there is a composed and relaxed man greeting me.

A mile of gravel road crosses the Winooski River over an old covered bridge, leading to Cate Farm. On a beautiful clear bright summer day, the long and lanky Richard Wiswall saunters over to warmly welcome me. Even though it’s a Monday morning in July in Vermont, during what should be the busy season, he’s full of smiles and exudes warmth and ease. Instead of a stressed-out, disheveled grower, there is a composed and relaxed man greeting me.

Like many farms, we have taken the paper pot plunge.

Like many farms, we have taken the paper pot plunge.