By Diane Szukovathy

It takes courage to farm, no way around it and no matter what you farm. If you are trying to pull a living from working the land, you learn to live with risk on a daily basis, in a way that earning a regular paycheck won’t teach. Most small-scale farmers I have met are exquisitely good at two things - living with uncertainty and producing quality product.

Getting the product sold is a whole other job - and one that many of us would just as soon not deal with. Even if we have time and a talent for it, market barriers for the small farmer to sell in volume can be brutal and constantly changing. The odds of creating or finding sales channels on your own that are efficient, profitable and stable enough to justify your time spent can seem impossible.

Case in point - my husband Dennis and I started a cut flower farm from scratch about twelve years ago. We love to grow flowers and we got pretty good at it, working up to five acres cultivated. But trying to get enough of those flowers sold profitably enough to pay our mortgage just about killed us.

Over a period of several years, we tried selling at farmers markets, reaching out to local floral wholesalers and running a bucket truck to the city. I’m not saying it can’t be done. Local market opportunities vary quite a lot. But we never came close to being able to quit our landscaping business, which was paying the bills. We’re stubborn and we wanted to farm full time. And make a living doing it.

What’s more, we didn’t want to expand our farm business into an empire in order to achieve our goals. We love the range of physical activity and exposure to nature and the seasons that owning a small-scale farm provides. Five years in, we were willing to do almost anything to make our dream work - including starting a co-op.

We put the word out and were fortunate to find eleven other farms who shared similar enough needs to ours to start a flower producer’s co-op. We incorporated the Seattle Wholesale Growers Market Cooperative (SWGMC) in February of 2011 for the purpose of creating shared marketing opportunities for our member owners.

We started with a simple leased space, basically an indoor farmer’s market model where each farm conducted their own business under a shared roof. The board of directors handled day to day operations. In that first year, co-op members generated $300,000 total sales revenue. We had one part-time employee in the position of front desk manager. It was bare bones and we farmers had to make tough decisions for the day-to-day survival of the business.

Right away, Dennis and I could see the potential for the co-op to solve our farm’s marketing needs. Our gross income jumped 84% during that first year. While running a bucket truck had been our most consistent and promising source of revenue, we could only stop at about ten florists in a run, whereas at the co-op we were able to serve thirty to fifty customers in a day. The new problem became how to keep the co-op alive.

Fortunately for us, the USDA understands farming’s culture of risk and recognizes the value of agricultural cooperatives. During the co-op’s first three years, we applied for and received grant funding through two different USDA channels - the Specialty Crop Block Grant Program and the Rural Development Value Added Producer Grant program. Knowing that we needed these funds to survive and lacking money to pay professional grant writers, we farmers wrote the grant proposals ourselves.

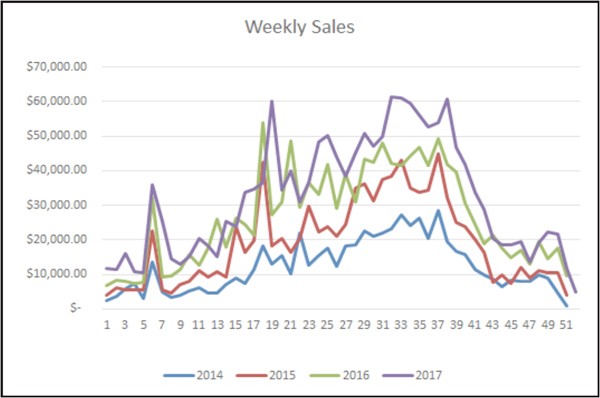

Fast forward six years - the co-op wrapped up 2017 with $1.68 Million in sales revenue - reflecting 460% growth since our first year. Qualified professional staff manage and run our operations. SWGMC currently has six full-time employees. In December, we relocated to a larger, more efficient space which will allow us to continue to grow toward a sales target of $3.1 million by 2021. We currently have fourteen solid members with an additional handful of farmers tracking toward membership at the end of this year.

While our growth trajectory has been healthy and impressive, making decisions and finding solutions on a daily basis to get us to this place has been alternately exciting, gut wrenching, flying blind unnerving, awkward, glorious and ridiculously hard work. Basically we have wrought our company from available resources, self-trained and without a roadmap.

Along the way, we’ve been smart enough to seek and fortunate to receive guidance from several high functioning business and cooperative development advisors. While facilitating our first board retreat in 2016, Margaret Lund, of Co-opera Co. introduced us to psychologist Bruce Tuckman’s forming-storming-norming-performing descriptions of stages for small group development, assuring us that our process has been normal. Good to know.

How did we get from there to here? While circumstances of market opportunity and available resources were unique to our time and place, I believe that some universal principles and values have helped determine our success to date. I read with keen interest Chris Bodnar’s article, Italy’s thriving agricultural co-ops, in the October 2017 issue of GFM, noticing that many of his observations for the success of those businesses were already built into our model.

Pay the price of owning yourself

There are no shortcuts to starting a cooperative, or maintaining one. Like parenting, it requires commitment, constant vigilance and adaptability - especially from the core leadership, who must be willing to make themselves vulnerable and be “all in.”

For me, starting a farm provided good practice for starting a co-op. No matter what you have to give, you operate in a realm of uncertainty, especially when the business is young. It will take what it does and someone has to get the work done or the thing won’t go.

Co-op leaders must be willing to compromise and to weave the visions of others into their own personal perspectives. This requires a commitment to personal growth work.

It is wise to lead with incentives rather than mandates. No farmer likes to be told what to do. Asking rather than compelling builds strong culture, but it may mean more work for leadership in the short run. The growth and survival of a co-op’s culture and business rely on setting and upholding fair policies and respecting the democratic process. This means that leaders work harder for the same benefits that every member enjoys equally. It therefore benefits the co-op to seek members with strong leadership potential.

Set a quality standard and hold it

“Dirty buckets and product exhibiting signs of prolonged wilt, excessive petal or leaf drop, mold, insect infestation, improper stage of harvest or other symptoms that might reasonably indicate poor quality will not be allowed,” has been the co-op’s standard from day one. We recognize that by selling our product together we must also work together to build and protect our brand. The same holds true for reliability and delivering on commitments.

In order to make decisions with our customers’ best interests in mind, the co-op has two industry liaison positions on our board of directors. During a discussion about a member’s repeated shortcomings, one of our liaisons famously stated, “I would rather buy from Satan than an unreliable supplier.”

Hire good people

USDA grant funds allowed us to hire a co-op manager. Although it took three tries to get the right fit, this step was a “norming” game changer, allowing us farmers to focus back on our farms and giving the reins to someone qualified in financial oversight and floral wholesaling. Molly Sadowsky has been our Market Manager for three years now and we credit her with transitioning the co-op into “performing” mode.

Molly is deeply committed to our mission, vision and company values - which are posted on the wall right as you walk into our business. Leadership from the owners, in stating our values and living by them, has helped us attract and keep talented and motivated staff.

Focus on the customer

All roads lead to customer service as a means of meeting our goals and keeping our business healthy. A healthy business sustains our farms. For this reason, the individual needs of any member always come second to the needs of our customers.

Floral is a highly perishable business and our customers operate under intense pressure to deliver high-end, quality design work. In order for them to trust us with their business, we must maintain a high standard of professionalism and deliverables. We compete straight-up in the marketplace with traditional floral wholesalers for product quality and selection. Providing local and sustainably grown products is part of our brand, but we don’t rely on asking our customers to “do the right thing” as a means of driving the business.

That said, in our most recent customer survey, 94% of respondents indicated that they shop with us because they, “value and want to support local flower farms.” 76% indicated that they, “want to support a vibrant community market place.”

Keep the membership engaged

Because there are so many moving parts - owners, board members, committee members, staff and customers - communication remains a primary, ongoing challenge. Our member farms are separated geographically from near the Canadian border in Washington, as far east as Walla Walla and south to Eugene, Oregon. This means we may not see each other in person that often.

It doesn’t matter how smart the decisions are that the board and staff make on behalf of the company. If the membership at large isn’t up to speed and sharing in the decision making process on some level, trust will erode.

We recently established a Member Engagement Committee to focus on this challenge. We encourage every member to serve on at least one committee, with meetings held electronically. At our secretary’s suggestion, we have begun posting board and committee meeting minutes online for all members to see. Transparency is our goal, and we often use Google Docs to share information and work on projects collectively.

Set fair policies

One of the biggest obstacles to starting a co-op has got to be fear of competition: How will it work if we all bring our products and there is too much to sell? What if one of the other growers undercuts my price? What if I invest in a perennial crop and then someone else comes in and floods the market two years from now?

We farmers generally want to show the side of ourselves that is generous, accommodating and willing to get along. And that is the predominant nature of most who are attracted to being part of a co-op. But, it’s a tough business and these fears are valid, even if most people won’t voice them out loud. Why would sensible and hard working growers invest themselves in a business without some assurance of maintaining solid market opportunities?

In our early years when we each sold from our own farm booths, farmers did a lot of natural dove-tailing and were fairly considerate of each other in crop selection and pricing. When we transitioned to having staff run our operations, we gave our manager the authority to set minimum pricing. She keeps abreast of the industry at large and works with us to make sure that our pricing is fair and consistent.

Coordinating crops presents a bigger challenge, especially as we continue to grow and add new members. Still a work in progress, we’ve created a four page Crop Coordination Policy that gives our staff leeway to make judgement calls for best customer service while keeping opportunities intact for growers who have a history of supplying any particular crop. New growers joining the co-op are assigned crops for which the market has gaps or growth opportunities (there are plenty). In that way, we help to foster a climate of trust and mentorship amongst our community of farmers and set up systems which encourage growers to use the co-op as their primary sales channel.

Unlike the Italian models, we do not require our members to sell exclusively through the co-op. Instead, we challenge ourselves to provide the best possible sales opportunities and trust that growers will recognize and take advantage of the benefits that we offer.

Growth and resilience

Our co-op will turn seven this spring. We are still somewhat vulnerable, only because we are a young company in growth mode and need time to build assets. That said, we continue to attract impressive human resources, both in our membership and on our staff.

We are actively planning our future and have a five-year strategic plan in place. Those of us who have served in key leadership roles on the board since our beginning recognize the need to give over to new leadership so that the co-op will not be hampered by founder’s syndrome.

We are also consciously mentoring and bringing young farmers into our membership.

From my experience, there is no halfway method of starting or maintaining a co-op. Even though the effort we had to put forth to create the business was Herculean, I already have no doubt the risk was worth it. We may well endure for generations.

Diane Szukovathy co-owns and operates Jello Mold Farm with her husband, Dennis Westphall. Their farm is located in Washington State’s Skagit Valley, where they grow a diverse range of floral crops. Diane is a founding member of SWGMC and has served as board chair since the co-op’s beginning.

For most established growers, the easiest place to start selling flowers will be mixed bouquets and single stem/small bunch retail sales. These are the flowers you can sell to your existing customers and they are easy to incorporate into farmers market, CSA, and grocery sales. But there are lots of other outlets out there, including florists, weddings and events, business subscriptions, value added products, and wholesalers.

For most established growers, the easiest place to start selling flowers will be mixed bouquets and single stem/small bunch retail sales. These are the flowers you can sell to your existing customers and they are easy to incorporate into farmers market, CSA, and grocery sales. But there are lots of other outlets out there, including florists, weddings and events, business subscriptions, value added products, and wholesalers.

With word that Amazon has purchased Whole Foods, farmers can be sure that the downward pressure on prices will continue. Farmers in many regions report declining CSA memberships and farmers market sales. Producers will have to think hard about the sustainability of their operations with regard to marketing and pricing amidst changing consumer expectations.

With word that Amazon has purchased Whole Foods, farmers can be sure that the downward pressure on prices will continue. Farmers in many regions report declining CSA memberships and farmers market sales. Producers will have to think hard about the sustainability of their operations with regard to marketing and pricing amidst changing consumer expectations.

Get things done and build community with a work party

Get things done and build community with a work party

Over the last 10 years, there has been a lot of information coming out pertaining to growing veggies in soil in greenhouses. We wanted to share some of what we’ve learned over the past 13 years growing flowers under plastic and touch on some new approaches we’ve implemented since we last wrote about greenhouse growing (see our GFM articles in November 2014, November 2015, and April 2018).

Over the last 10 years, there has been a lot of information coming out pertaining to growing veggies in soil in greenhouses. We wanted to share some of what we’ve learned over the past 13 years growing flowers under plastic and touch on some new approaches we’ve implemented since we last wrote about greenhouse growing (see our GFM articles in November 2014, November 2015, and April 2018).

Farming in any location is challenging. Imagine the challenge of growing crops at latitude 54.5° where winter temperatures hit minus 40° Celsius (minus 40° Fahrenheit) and a mere 100-day growing season can be abbreviated with a large dump of snow at the beginning of September. Meanwhile during the spring, Chinook winds blow and the high latitude’s strong sun alters flowers’ growing cycles.

Farming in any location is challenging. Imagine the challenge of growing crops at latitude 54.5° where winter temperatures hit minus 40° Celsius (minus 40° Fahrenheit) and a mere 100-day growing season can be abbreviated with a large dump of snow at the beginning of September. Meanwhile during the spring, Chinook winds blow and the high latitude’s strong sun alters flowers’ growing cycles.

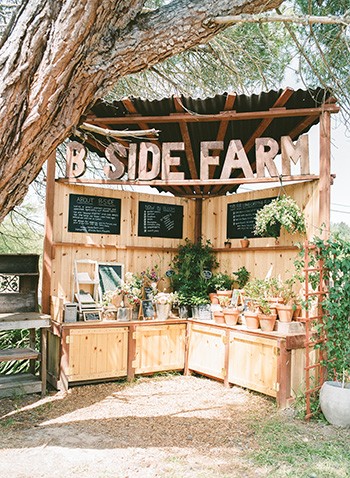

Northern California is beautiful in its own unique way in August, with dried out hills covered in brown grass and widely branched, stately live oaks sprinkled around, and a

Northern California is beautiful in its own unique way in August, with dried out hills covered in brown grass and widely branched, stately live oaks sprinkled around, and a

Part 1 of this series discussed why and how to add cut flowers to your farm. This part discusses production in more detail, especially harvest and post-harvest handling. Part 3 will focus on marketing.

Part 1 of this series discussed why and how to add cut flowers to your farm. This part discusses production in more detail, especially harvest and post-harvest handling. Part 3 will focus on marketing.

As soon as we start driving our routes in the spring our customers ask us when we’ll have roselilies. They’re that popular and have become a signature crop for us. They’re basically a type of oriental lily, but with multiple layers of petals, and without stamens and pistils (i.e. no pollen!).

As soon as we start driving our routes in the spring our customers ask us when we’ll have roselilies. They’re that popular and have become a signature crop for us. They’re basically a type of oriental lily, but with multiple layers of petals, and without stamens and pistils (i.e. no pollen!).

Fifth Crow Farm lies nestled below some ragged hills – the native grass fully brown, the oaks wide and green. The farm grows 50 acres of certified organic crops on 150 acres of leased land, including vegetables, cut flowers, dry beans and eggs. The farm land is completely flat, tucked in a tiny valley in zone 9B. Believe it or not, just across the street, a mere two miles from the ocean, there are acres and acres of open land with cows grazing. How can land so close to such beauty, and with such a wonderful growing season be devoid of development? The answer is complicated, but mostly it’s because the parcels of land have always been quite large, and much of it is being purchased for conservation purposes.

Fifth Crow Farm lies nestled below some ragged hills – the native grass fully brown, the oaks wide and green. The farm grows 50 acres of certified organic crops on 150 acres of leased land, including vegetables, cut flowers, dry beans and eggs. The farm land is completely flat, tucked in a tiny valley in zone 9B. Believe it or not, just across the street, a mere two miles from the ocean, there are acres and acres of open land with cows grazing. How can land so close to such beauty, and with such a wonderful growing season be devoid of development? The answer is complicated, but mostly it’s because the parcels of land have always been quite large, and much of it is being purchased for conservation purposes.