Post your favorite farm-made tool using #toolsforgrowingformarket. Or email us your idea at [email protected]. If Josh picks your tool, you win a $50 tool gift certificate and a Full Access sub to GFM.

This article originally appeared in the March 2020 issue of Growing for Market Magazine.

I’m a sucker for carts, as some of you might guess, having designed a few versions myself. Reid Allaway of Tourne-Sol Cooperative Farm in Québec, Canada, tagged a number of excellent tools with #toolsforgrowingformarket and his Tall Straddle Cart caught my attention as a unique design I hadn’t seen before but that looked, and sounded useful. I picked it as the first tool from another farmer to highlight in this new column.

Like many of the tools I’ve built myself, Reid didn’t actually come up with the concept himself, it’s something that he got from another market farmer in Québec, Michel Massuard. At Tourne-Sol they’ve found the cart useful enough that they’ve needed to build two of them. It is also a tool that Reid continues to tinker with, making small improvements over time.

The initial impetus for the cart design was hauling zucchini and summer squash out of beds that are more than 100 feet long. By hand this is a heavy and slow job but the cart makes the job much more reasonable. The load is primarily supported by a single wheel in the pathway where the harvester works.

The tall straddle cart loaded with totes and bulb crates. It can be pushed or pulled by the handle.

In front of and behind the wheel are platforms made from a bit of angle iron to hold harvest totes. Under each of the platforms are skids that keep the cart from tipping too far forward or back, but the skids are a few inches off the ground when it is rolled along by either pushing or pulling a handle attached to the front platform. A second wheel acts as an outrigger to keep the cart from tipping over sideways and that wheel is attached with a kind of bridge that is high enough to comfortably clear a full-sized summer squash plant.

Reid made the frame of the cart from salvaged 1” steel square tube and scraps of flat stock and rebar. The only other parts are two bicycle wheels. Their cart was just upgraded to use one 4” fat tire (slightly modified) on the load bearing wheel, and a narrower mountain bike front wheel on the outrigger side. The previous version used two salvaged mountain bike front wheels and regularly handled loads of 300 pounds with no structural failures. The whole thing was put together using a welder (MIG, but any welder would work) and an angle grinder.

In practice on the farm the carts get used for summer squash and lettuce harvests. For summer squash harvests, empty totes are dropped at regular intervals and then filled and left in the aisle. The cart is then rolled down the bed and harvest totes are stacked, evenly front to back, up to five high for a total of ten in a single load.

Lettuce is harvested similarly to the summer squash, with totes being pre-dropped and then collected when they are full. The lettuce totes are a little taller, so they are stacked a maximum of four high for a total of eight, with one particularly bold harvester sometimes adding a ninth tote to the stack nearest to him. The problem with overloading the cart is less about weight, and more that tall stacks become unstable, especially traveling over bumpy ground.

Unloaded you can see how the entire cart was made with angle iron, metal tubing and rebar.

This is the final version of the cart with a 4” fat tire on the load bearing side.

Photos courtesy of the author.

One problem with the cart is that the load carrying wheel is centered with the load and so with large loads on bumpy terrain sometimes the counterweight of the outrigger wheel isn’t enough to keep the load from tipping away from the outrigger. To solve this problem Reid has added extra weight to the outrigger, but he suggests that it might work to move the load bearing wheel further outboard to line up with the outer edge of the totes. The carts also have a minimal rebar wire frame helping prevent tote stacks from tipping inward when traveling over bumpy ground, and this too might be better placed on the outside rather than the inside.

In my conversation with Reid about his cart we also talked a bit about his involvement with the CAPÉ Autoconstruction project. The CAPÉ is an agricultural cooperative serving direct-marketing farms. The Autoconstruction (self-build or DIY) group is modeled after a similar French enterprise called L’Atelier Paysan.

Both of these projects bring together groups of farmers to build farm equipment in batches, for themselves, sharing basic fabrication tools, skills and designs, and creating stronger networks among regional growers. The CAPÉ Autoconstruction has been running winter workshops for six years now and L’Atelier Paysan formally organized in 2011. Both of these organizations are primarily French speaking, but they also both have forums on Facebook that are auto-translated and Reid tells me that questions in English are welcome.

Josh Volk farms in Portland, Oregon, and does consulting and education under the name Slow Hand Farm. He is the author of the book Compact Farms: 15 Proven Plans for Market Farms on 5 Acres or Less, available from Growing for Market. He can be found at SlowHandFarm.com.

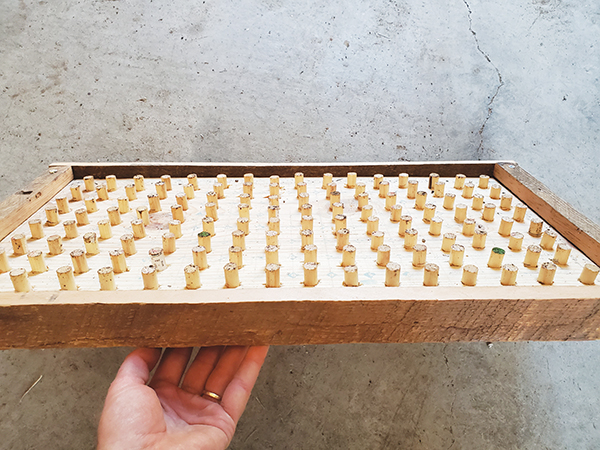

Megan French from Boundless Farmstead near Bend, Oregon, posted these dibblers she built on Instagram and reminded me that I need to get my act together. On their farm they’re typically seeding 30 to 100 trays per week with a vacuum seeder. To get evenly dibbled holes before making the dibbler boards they were using a single bolt with a nut and washer to set the depth. One. Cell. At. A. Time. Which understandably was slow.

Megan French from Boundless Farmstead near Bend, Oregon, posted these dibblers she built on Instagram and reminded me that I need to get my act together. On their farm they’re typically seeding 30 to 100 trays per week with a vacuum seeder. To get evenly dibbled holes before making the dibbler boards they were using a single bolt with a nut and washer to set the depth. One. Cell. At. A. Time. Which understandably was slow.

When I saw this tool I knew the exact need that inspired its creation and I loved seeing the abundant comments from other farmers around the world who had also created their own versions, born of that same common need. Nat Wiseman from Village Greens of Willunga Creek near Adelaide in southern Australia posted a very simple and relatively quick fix to the problem of laying drip lines in garlic after the canopy has already filled in.

When I saw this tool I knew the exact need that inspired its creation and I loved seeing the abundant comments from other farmers around the world who had also created their own versions, born of that same common need. Nat Wiseman from Village Greens of Willunga Creek near Adelaide in southern Australia posted a very simple and relatively quick fix to the problem of laying drip lines in garlic after the canopy has already filled in.

Another simple and relatively inexpensive tool drew me in on social media this month – a magnet in the place of a knife sheath submitted by Kat Johnson, the Produce Manager at Fields Edge Farm in Floyd, Virginia.

Another simple and relatively inexpensive tool drew me in on social media this month – a magnet in the place of a knife sheath submitted by Kat Johnson, the Produce Manager at Fields Edge Farm in Floyd, Virginia.

Until two years ago I was germinating all seedlings in greenhouses using almost exclusively bottom heat from electric heat mats. At my current farm we only had space for about 8-10 trays on our two mats and we definitely noticed differences in the germination (and presumably the heat the mats were providing) on the edges of our trays.

Until two years ago I was germinating all seedlings in greenhouses using almost exclusively bottom heat from electric heat mats. At my current farm we only had space for about 8-10 trays on our two mats and we definitely noticed differences in the germination (and presumably the heat the mats were providing) on the edges of our trays.

We’re very excited to tell you about a new feature in GFM. As farmers you are out there jury-rigging, farm-hacking, adapting and making new tools. We want to ask you to post or send photos of your tool and equipment ideas that would be useful to fellow farmers.

We’re very excited to tell you about a new feature in GFM. As farmers you are out there jury-rigging, farm-hacking, adapting and making new tools. We want to ask you to post or send photos of your tool and equipment ideas that would be useful to fellow farmers.

Weddings are a huge opportunity for local flower farmers, especially with the growing awareness of and demand for seasonal, sustainable flowers. And, if there is one time that people really want special flowers, it’s at their weddings.

Weddings are a huge opportunity for local flower farmers, especially with the growing awareness of and demand for seasonal, sustainable flowers. And, if there is one time that people really want special flowers, it’s at their weddings.