Sometimes you have the time and space to grow everything you want. That’s wonderful! Other times, either land, labor or both are in short supply. What to do? How do you decide which crops to grow? I’ve looked at this problem several times, and taken note when other farmer/writers tackle the topic.

Sometimes it is possible to reduce waste, increase productivity, increase efficiency, and make more use of crops you have in abundance. If space is short you can sometimes plant closer, use transplants rather than direct seed, plant faster-maturing varieties, relay-plant one crop while the previous one is still growing, interplant a tall crop in a bed of a short crop, use rowcover to speed up maturity, and various other tricks of the trade. Here I am going to focus on shortage of time/shortage of labor, rather than shortage of land.

Carrots are labor efficient, high yielding and popular, but not fast growing. Photo by Bridget Aleshire.

As in all farming, it’s best to make a plan that fits your resources. But sometimes the situation changes and less time is available than you thought. In years when we’ve been short of labor we have created a “can’t do it all” list. We list some labor intensive crops along with their respective “decision dates,” the month that is most labor-intensive for that crop, how expensive it would be for us to buy that crop rather than grow our own, and a few other factors.

We list the crops in order of decision date, then as each date approaches we review our situation and decide to keep it, grow less of it or get rid of the crop altogether. This method enables us to make one decision at a time, in a straightforward way, and not go insane. Such a list leaves the door open for possible upturns of fortune later in the year. It’s less distressing to take one bite at a time than to make a big decision when you already are struggling to cope with some calamity. When is it time to cut your losses? Farming never stands still, sometimes the best way to catch up with an interminable list is to remove some items, whether you’ve done them or not. I wrote about this in the February 2013 issue of Growing for Market in an article called “Making good decisions under pressure.”

Using such a list in 2011 and 2013, we looked at 35 crops: fava beans, sweet peppers, eggplant, bulb onions, multiplier onions, shallots, spring spinach, spring kale, peas, spring carrots, celeriac, celery, cantaloupe, edamame, peanuts, leeks, asparagus beans (yard-long beans), watermelon, cowpeas, lima beans, okra, paste tomatoes, green beans, sweet corn, summer lettuce, cucumbers, summer carrots, drying beans, fall broccoli, fall kohlrabi, strawberries, fall carrots, fall radishes, fall turnips, and raspberries. These were listed in date order, with decision dates running from 3/15 to 8/6.

Since 2013, we have stopped growing 14 of those crops: fava beans, bulb onions, multiplier onions, shallots, celeriac, celery, edamame, peanuts, cowpeas, lima beans, drying beans, kohlrabi, strawberries and raspberries. We have cut down on 7 more: eggplant (better varieties were more productive, fewer plants were needed), paste tomatoes and watermelon (we’re selecting our own seed varieties of both to improve productivity), green beans and cucumbers (we re-configured our succession planting dates of those two and reduced the number of plantings), summer carrots (we only grow them if we run short on spring carrots), and summer lettuce (we decided to go without for a month when growing it is most challenging). Having some clear crop characteristics to base our decisions on really made the sad task easier. The process has led me to look out for information from other growers on what informs their decisions.

Jean-Martin Fortier in The Market Gardener: A Successful Grower’s Handbook for Small-Scale Organic Farming (available from Growing for Market) deftly illustrates the importance of farming to meet your goals and fit your resources. He explains why 35 beds of their 160 bed total grow mesclun – it’s #2 in sales rank, despite being only #19 in revenue/bed. Salad mix only takes 45 days in the bed, and then another crop is grown, increasing the income for the bed. Our climate is very different from Quebec. Our market is very different. We don’t want 300 pounds of salad mix each week! We’re providing for 100 people year-round. We do want potatoes, sweet potatoes, carrots and winter squash to feed us all winter.

We’re currently constrained not by shortage of land, but shortage of labor. Some crops offer more money for the area, some are more profitable in terms of time put in. A crop which quietly grows all season from a single planting early on, when time is less frantic, can be an advantage. If the same plants provide multiple harvests, this can be great value for time. Leafy greens are the best example.

In High-Yield Vegetable Gardening, Colin McCrate and Brad Halm point out that when planning what to grow, it’s important to consider how long the crop will be in the ground, especially if you have limited space. Cindy Conner deals with his aspect in Grow a Sustainable Diet: Planning and Growing to Feed Ourselves and the Earth. The book leads you through the process of identifying suitable crops for food self-reliance, and provides a worksheet to help you determine “Bed Crop Months.” For each bed, determine how many months that food crop occupies that bed and so assess the productivity value of one crop compared with another. Short season crops grow to harvest size in 30-60 days, allowing a series of crops to be grown in the space, and feeding people quickly. Her method also makes explicit how much space is given to growing cover crops to replenish the soil. If all your nutrients were to come from your own garden, you would need to pay attention to growing enough calories. Otherwise you’d lack the energy to get to the end of the season!

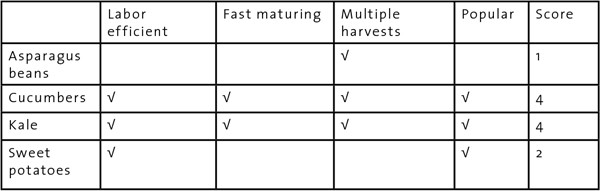

Curtis Stone, in The Urban Farmer (available from Growing for Market), distinguishes between Quick Crops (maturing in 60 days or less) and Steady Crops (slower maturing, perhaps harvested continuously over a period of time). He has designed a crop value rating system based on five characteristics. To use this assessment, you look at each characteristic and decide if the particular crop gets a point for that characteristic or not. Then look for the crops with the highest number of points. Spinach gets all five points; cherry tomatoes only three. The smaller your farm, the higher crops need to score to get chosen.

His five criteria are:

Shorter days to maturity (fast crops = chance to plant more; give a point for 60 days or less)

High yield per linear foot (best value from the space; a point for1/2 pound/linear foot or more)

Higher price per pound (other factors being equal, higher price = more income; a point for $4 or more per pound)

Long harvest period (= more sales; a point for 4 months or longer)

Popularity (high demand, low market saturation)

Richard Wiswall’s The Organic Farmer’s Business Handbook (available from Growing for Market) will help growers determine which crops bring the best income from the land. He teaches us that outdoor kale can produce $2463 from 1/10 acre, and of the crops he compared, only parsley and basil earned more. Field tomatoes came in at $1872, and several vegetables (bush beans, sweet corn, peas) made a loss. His book includes crop budgets for 24 crops. Richard Wiswall has the gift of making spreadsheets nice and easy, clear and useful. And the book includes a CD you can copy and use to create budgets, timesheets, a payroll calculator, and a farm crew job description template as well as the Vermont Farm Viability Enhancement Program Farm Financials Workbook.

Clifton Slade at Virginia State University in his 43560 Project shows how to earn $43,560 from one acre ($1 per square foot), four times the return of a typical large-scale commercial vegetable production. He recommends choosing crops which produce one vegetable head or stalk, or 1 pound of produce, per square foot. Leafy crops feature prominently. Clif describes his ‘Blue Ridge’ kale as “labor intensive but lucrative,” as each plant produces a bushel of greens over several harvests. He recommends beets, bok choy, cabbage, carrots, cut flowers, garlic, potatoes (especially fingerlings), lettuce, daikon radishes, onions, Swiss chard, and turnips.

Vern Grubinger in Sustainable Vegetable Production from Start-up to Market explains how to make an enterprise budget for each crop. These calculations compare the financial value of one crop with another, while not delving into overhead costs. In your crop journal, record the amount of work done on each crop each day. Keep harvest records of quantity, time and money from sales. At the end of the season, add up the total time for each crop, divide the income for that crop by the time spent on it, and divide the income for that crop by the area, or number of beds. Aim for a minimum of $400/100’ bed per season. The range could be anywhere from $109-1065.

Sweet potatoes are not quick to harvest, but they are labor efficient and provide for a long sales season from a single bulk harvest. Photo by Nina Gentle.

Which crops take the most attention? Steve Solomon in Gardening When it Counts provides tables of vegetable crops by the level of care they require. Crops that are generally trouble-free and only demand low to medium soil fertility are rated as easiest to grow. He lists kale, collards, endives and chicories, spinach, cabbage; potatoes, sweet potatoes, tomatoes (followed by the more difficult eggplant, peppers); all cucurbits; beets and chard, sweet corn, all legumes, and okra. His “harder to grow” list includes lettuce, arugula, parsley, carrots, parsnips, broccoli, radishes, kohlrabi, turnips, rutabagas, mustards and non-heading Asian greens, scallions, potato onions, topsetting onions and garlic. His “difficult” list (requiring adequate soil moisture and/or very fertile soil and/or having other special challenges) includes bulb onions, leeks, Chinese cabbage, asparagus, celery and celeriac, cauliflower, Brussels sprouts. My personal “difficult” list (and my climate) is different, but the principle is a useful one.

In The Lean Farm: How to Minimize Waste, Increase Efficiency, and Maximize Value and Profits with Less Work (available from Growing for Market), Ben Hartman explains the five principles of “Lean,” the first of which is to precisely specify what the customers value (not just the products, but also the presentation, timing, and packaging or not). The important bit is not what you think they ought to value, but what they actually value. Observe and ask. Find out which of your activities with each crop add value and which add waste. Avoid being distracted by fascination with gadgets or complexity; weird and wonderful shapes and colors of vegetables; unusual methods of growing crops; or letting supply determine your assessment of value. More kale is not always better! Customers usually value a mix of goods and services such as presentation or reliable deliveries.

In Market Farming Success: The Business of Growing and Selling Local Food (available from Growing for Market), Lynn Byczynski devotes eight chapters to identifying and explaining aspects of market farming that new growers need to tackle. The book covers getting started, finding markets, choosing crops to grow, tools and equipment, planning, crop production, post-harvest handling and business management. She points out to new market growers that you need a diversity of crops, not just a few profitable items. In addition to early crops, you need critical mass for the whole of your chosen season. Grow what yields well for least labor, grow what sells best at the highest price, and also grow what fills gaps between your major crops. Other reasons to grow crops that don’t make the highest income include providing a good crop rotation for your farm, providing for different times of year, and providing diversity (customers will only buy so much parsley and basil).

Factors to consider

Putting together these various ideas, here’s my list of possible points. Loosely speaking, there are six over-arching categories: time (1-4), yield (5-8), income (9-10), demand (11-15), strategic importance (16-20) and complexity (21-25).

Time

1. Is it labor efficient? (Some space-hogging crops like sweet corn are not labor intensive.)

2. Does the intense work for this crop come in at a less-busy time of year?

3. Is this crop fast-maturing? (If labor is short, weed control might be an issue for a slow-growing crop, even if space isn’t.)

4. Is it high yielding for the labor intensiveness? (Okra doesn’t provide much food for the space or the time.)

Yield

5. Is it high yielding for the space occupied (does it produce one vegetable head or 1 pound of produce, per square foot or1/2 pound/row foot)?

6. Is it high yielding for the time it occupies the ground (if space is short)?

7. Does it provide multiple harvests from a single planting?

8. Does it provide a single bulk harvest of a storable crop?

Income

9. Does it bring a high price, above $4 per pound?

10. If you are growing for a household, or a non-profit, or considering buying wholesale from another farmer for your CSA: Is it expensive to replace?

Demand

11. Is it popular (do you have a good market for it)?

12. Is it a staple?

13. Does it store well/easily?

14. Does it provide harvests at times of year when other crops are scarce?

15. Does it provide appealing diversity for your booth or CSA boxes?

Strategic importance

16. Is it a resilient “insurance crop” (forgiving of bad weather) which comes through when other crops fail?

17. Does it help provide your land with a good crop rotation?

18. Is it in the Dirty Dozen? (What are the pesticide levels in the non-organic crop, if that’s your alternative source?)

19. Are you relying on this crop for personal sustenance?

20. Is it nutritionally dense or important (a protein crop, an oil crop, a mid-winter crop)?

Complexity

21. Is it reliably easy to grow? Or fun or pleasantly challenging to grow?

22. Is there minimal wastage/maximum saleable quality of the harvested crop?

23. Does the crop require minimal processing to be ready for sale?

24. Is its peak period for water use at a time when you have plenty of water?

25. Will it grow without a fence for deer/rabbit/bird protection? (Thanks, Debby Jaffe, for the last two points.)

Chart your relevant factors

First, be clear about your farming goals – some of these factors will be more important to some growers than to others. Rearrange the list to suit your farm, select 6-10 of the most important factors and make up a chart. List all the crops you are growing (or might grow). Assess the crops as objectively as you can. Then award each crop a point for each check mark. Knock out the crops with fewest checks. If you need a tie-breaker, you could use secondary factors from the list.

Other approaches

And if all this careful logical decision-making leaves you cold, Atina Diffley in Turn Here Sweet Corn describes the “Diffley Deal” when they needed to downsize their workload. This is a simple method for small groups of people who know each other well, and have developed high trust. Each person could choose one crop each to cut, in turn, until they got down to what they could manage.

Mark Cain of Dripping Springs Garden, Arkansas, points out that 50% of their growing area is in cut flowers and 50% in vegetables, but the cut flowers bring in 75% of the income. If you need more income for your time, add in some flowers.

Price and quantity

The Iowa State University publication Determining Prices for CSA Share Boxes compares pricing based on either what customers will pay, what other growers are selling the crop for or what it costs to produce. It includes a chart of share value of 24 crops based on grocery prices and the quantity included.

The average person eats 160-200 pounds of fresh vegetables per year (USDA). The average CSA share feeds 2 or 3 people, so an annual share will need to include about 500 pounds of 40-50 different vegetables, if it is providing sharers with all their produce for the whole year.

To calculate how much to grow to achieve your harvest goals, take the likely yields and add a margin for culls and failures (10%?). The table I provide in Sustainable Market Farming (available from Growing for Market) lists 48 crops, with likely yield, quantity required for 100 CSA shares, and length of row needed to grow this amount.

Pam Dawling grows vegetables at Twin Oaks Community in central Virginia. Her book, Sustainable Market Farming is widely available, including by mail from Sustainable Market Farming, 138 Twin Oaks Road, Louisa, Virginia, 23093. Enclose a check (payable to Twin Oaks) for $40.45 including shipping. Pam’s blog is on her website www.sustainablemarketfarming.com, and on facebook.com/SustainableMarketFarming.

Here's a system to track all those details

Here's a system to track all those details

Since its founding in 1968 by my husband Eliot Coleman, Four Season Farm has sought to produce the best vegetables possible, using soil-based organic methods, on a small amount of land. When I showed up in 1991, Eliot had begun to pioneer winter vegetable production, and I was delighted to give up the landscape design business I’d run in Connecticut and grow veggies with him. Then, about 10 years ago, flowers started to creep in.

Since its founding in 1968 by my husband Eliot Coleman, Four Season Farm has sought to produce the best vegetables possible, using soil-based organic methods, on a small amount of land. When I showed up in 1991, Eliot had begun to pioneer winter vegetable production, and I was delighted to give up the landscape design business I’d run in Connecticut and grow veggies with him. Then, about 10 years ago, flowers started to creep in.

If you’ve been a subscriber to Growing For Market (or even if you haven’t), you’re probably familiar with the many advantages of no-till agriculture. No-till methods can reduce a farm’s carbon footprint, promote complex soil biology, and preserve and build organic matter.

If you’ve been a subscriber to Growing For Market (or even if you haven’t), you’re probably familiar with the many advantages of no-till agriculture. No-till methods can reduce a farm’s carbon footprint, promote complex soil biology, and preserve and build organic matter.

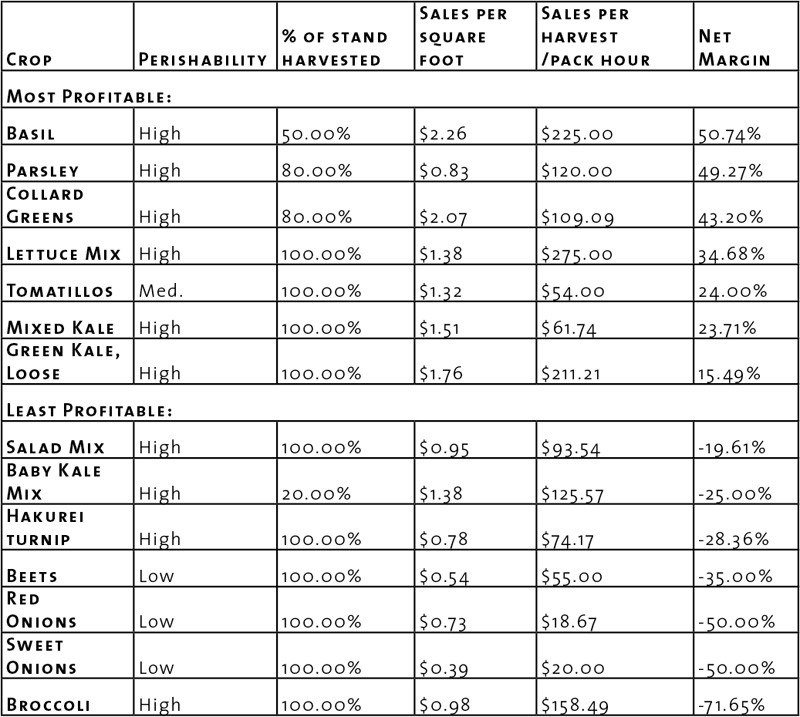

Those of you who read my last article in the May 2018 Growing for Market remember that the method we use to evaluate the potential profitability of our crops is to calculate the “unit cost” for each crop - that is, the minimum price we would need to receive in order to pay all of our expenses and ourselves. Calculating unit cost also provides us with the ability to compare the relative profitability of each crop by comparing each crop’s net margin (Net margin = (Price received - unit cost) / price received).

Those of you who read my last article in the May 2018 Growing for Market remember that the method we use to evaluate the potential profitability of our crops is to calculate the “unit cost” for each crop - that is, the minimum price we would need to receive in order to pay all of our expenses and ourselves. Calculating unit cost also provides us with the ability to compare the relative profitability of each crop by comparing each crop’s net margin (Net margin = (Price received - unit cost) / price received).