Avoiding the pitfalls of over-planting, something we are all susceptible to in the enthusiasm of winter seed ordering and spring planting, frees up time for more important things and results in better profits. Although it can be hard to see in the cold of winter, planting more than you know you will sell impacts your farm’s efficiency and your satisfaction. Using records and sticking to them can keep you from putting too many plants and seeds in the ground. Fine-tune your system toward growing what you can sell rather than scrambling to try to sell what you’ve grown.

On our farm, over-planting starts in the winter when we’re curled up by the fire with a stack of tempting seed catalogs, enticed by all of those new varieties. Or when we place our order and realize it’s just a few more dollars to buy a pound of seeds instead of an ounce. Once in the greenhouse, it’s easy to plant extra trays; there always seem to be just a couple more seeds left in the packet that are begging for soil. Out in the field when it’s time to transplant, making room for the plants leftover in the plug flat sounds reasonable. It’s hard to compost plants that have the potential to yield healthy crops. And the fields always look shockingly empty in early spring, prompting us to quickly fill up the beds.

The author getting set up at a market. All images courtesy of Emily Oakley.

A little over-planting is part of sound farming. Building in a cushion of extra crops is a form of insurance against unpredictable weather patterns and changing customer demands. What if it’s raining when we’re scheduled to plant our next succession? What if a freeze sets back our earlier seeding? Or, what if this is the year customers go crazy for arugula? These are the sorts of questions that run through our minds as each new season gets going, and they can make it hard to stick to our original planting schedule.

While budgeting in room for additional plantings is part of the farming process, having too much of a good thing can create unwanted stress during a busy time of year. All of those extra rows and beds need weeding, irrigating, and tending. Once the plants are in the ground and thriving, we feel compelled to take care of them. And by the time they are lush, beautiful, and ripe for picking, it’s hard not to harvest them. But if our records consistently show that those extra plantings aren’t increasing our bottom line, they are probably taking away from our profit rather than adding to it.

The first line of defense against over-planting is thorough record keeping. Each season we maintain an informal list of things to do or not do the following season, including thoughts on over-planting. It can be written on a piece of paper tacked to the fridge, be created in a Word document on the computer, or be jotted down in the Notes section of a smart phone. Sometimes we send ourselves texts or emails to serve as a reminder to add an item to the Notes for Next Season. We’ve used the Voice Memo feature on our smartphone to capture an idea when our hands are too dirty to write something down. The hardest part about this process is making ourselves commit the thought to paper when we think of it. The more years we farm, the more we realize how quickly an idea can slip our minds as we try to keep track of so many moving parts in a day or week. After forgetting lessons and repeating the mistake again the next year, we’ve become more committed to writing ideas down as we think of them.

Here’s an example from our notes this past season:

1) Kale – White Kale is way better than Red Russian. Only plant a full bed for the first planting—only need two rows for all subsequent plantings.

2) Spinach-- Starting in May we don’t sell as much spinach. Only need 2 rows of spinach per planting.

3) Salad Mix-- Only two or three rows of salad mix per bed, except for the 1st planting (1 full bed and cover). Plant every week.

When it’s time to organize our planting schedule each winter, we print out these notes and modify our plans accordingly.

Over-planting isn’t just a spring phenomenon. While we grow over three-dozen different crops, tomatoes remain our primary cash crop. Because they are so important to our bottom line, we’re particularly susceptible to adding a bed or two at the last minute for good measure. We’ve experienced enough volatility in weather over the years—from severe heat that caused blossom drop to rain-forest like levels of rain and the attending diseases—to know that we feel better buffering in a little more than we need rather than a little less. But we’ve also taken that thinking too far and found ourselves swamped in tomatoes, so many that we couldn’t pick them all. Not only does it hurt to see a valuable cash crop rotting on the vine, no one wants to spend the time staking and tending tomatoes that won’t sell.

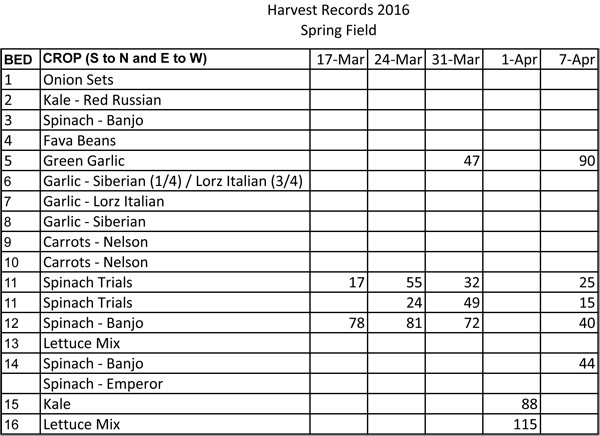

This is where record keeping comes into play again. In addition to our notes for next season, we keep an Excel planting schedule in which each row in the spreadsheet represents a row or bed in the field. We then copy the planting schedule into another Excel document, and it becomes our harvest records. We hand-write out a daily or weekly pick sheet that we keep on a clipboard in our wash station. We weigh or count out each item we harvest after cleaning and before putting it in the cooler. We use the pick sheet to set up our Quickbooks market sales receipt that lists each item we bring to market and its quantity and how much we sold of each thing (we likewise weigh or count out what remains unsold at the end of each market). We also use the pick sheet to fill out our harvest records each week. The columns in the Excel spreadsheet represent the date of harvest, and we enter the amount harvested for each row or bed, depending upon the level of detail we are looking for.

Below is an example of the author’s harvest record sheet, which is generated from the planting schedule. She compares what was harvested with what was sold to track how much of any crop was sold vs. how much was harvested.

At the start of each season, we look back at our previous year’s planting schedule, harvest records, and market sales receipts to help us gauge where and what we over-planted and to correct for that on the new year’s planting schedule. One helpful feature of these records is that they also show us the reverse: those crops that we need to plant more of and when. Quickbooks has a simple reporting feature that allows us to see our sales by item and the percentage of our total sales each crop represents. This has helped us cut out some crops that didn’t generate sufficient income for the labor required. Although we loved the challenge of learning to successfully grow celery in Oklahoma, our records helped confirm our personal observations that the crop just wasn’t earning us enough income to justify the effort.

This might appear overly detailed to some, but we find it only takes a few minutes out of our day and gives us invaluable information at the end of the growing season. By not spinning our wheels too hard in the field on over-planted crops, we can use the time saved to make sure we keep our records current. Over the past thirteen years, records have helped us scale down the amount of land we cultivate while increasing our income.

The growing season is always a juggling act with more to do than can ever be done. Taking care of well-intentioned extra plantings that we won’t end up selling just adds to the burden. Whatever psychological benefit there is to abundance can be rapidly offset by the stress of trying to keep up with the weeding, watering, etc. on beds we won’t sell. Allocating precious resources to harvesting crops we can’t unload means less time picking crops we know we have a reliable market for. It can ultimately be more profitable to spend time harvesting something relatively labor-intensive like fava beans over a crop that is quick to pick and pack like head lettuce if we know we’ll sell the fava beans. Similarly, space taken up in our market truck for too much baby kale at the expense of something that will sell better is missed income.

After having a child four years ago, some of the tasks we used to do routinely started to feel less important. Pre-child, spending a few added hours at the end of the day harvesting salad mix that wasn’t going to hold another week seemed like a good use of our time. Now we have other things we need to be doing, like eating dinner at a decent hour as a family. So unless our records show us that those extra boxes are likely to get sold, we would now rather think of them as a cover crop than waste time picking too much at the expense of balancing our work and family.

Each season is so different that what fails one year can be a bumper crop the next. Customers can surprise us and go nuts for something they didn’t give a second glance to the previous season. But when you have enough years of records, trends start to emerge. There’s no way to avoid some amount of hustling to sell abundant harvests. Yet if looking over records and giving yourself the space to listen to your own observed wisdom can curtail some over-planting, the payoff is rich.

Emily owns Three Springs Farm in eastern Oklahoma and grows 6 acres of certified organic fruits and vegetables.

Here's a system to track all those details

Here's a system to track all those details

Since its founding in 1968 by my husband Eliot Coleman, Four Season Farm has sought to produce the best vegetables possible, using soil-based organic methods, on a small amount of land. When I showed up in 1991, Eliot had begun to pioneer winter vegetable production, and I was delighted to give up the landscape design business I’d run in Connecticut and grow veggies with him. Then, about 10 years ago, flowers started to creep in.

Since its founding in 1968 by my husband Eliot Coleman, Four Season Farm has sought to produce the best vegetables possible, using soil-based organic methods, on a small amount of land. When I showed up in 1991, Eliot had begun to pioneer winter vegetable production, and I was delighted to give up the landscape design business I’d run in Connecticut and grow veggies with him. Then, about 10 years ago, flowers started to creep in.

Dahlias were our number one crop this year, even beating out lisianthus and ranunculus by a landslide. We have tried many different methods of growing them, and these are the solutions we’ve come up with. I’m sure there are still better ways, and if you know of any, definitely send them our way! This year we planted 7,000 dahlias and plan to plant even more next year as we increase our growing space. Let’s just start at the beginning with planting and work our way through the whole process.

Dahlias were our number one crop this year, even beating out lisianthus and ranunculus by a landslide. We have tried many different methods of growing them, and these are the solutions we’ve come up with. I’m sure there are still better ways, and if you know of any, definitely send them our way! This year we planted 7,000 dahlias and plan to plant even more next year as we increase our growing space. Let’s just start at the beginning with planting and work our way through the whole process.

If you’ve been a subscriber to Growing For Market (or even if you haven’t), you’re probably familiar with the many advantages of no-till agriculture. No-till methods can reduce a farm’s carbon footprint, promote complex soil biology, and preserve and build organic matter.

If you’ve been a subscriber to Growing For Market (or even if you haven’t), you’re probably familiar with the many advantages of no-till agriculture. No-till methods can reduce a farm’s carbon footprint, promote complex soil biology, and preserve and build organic matter.

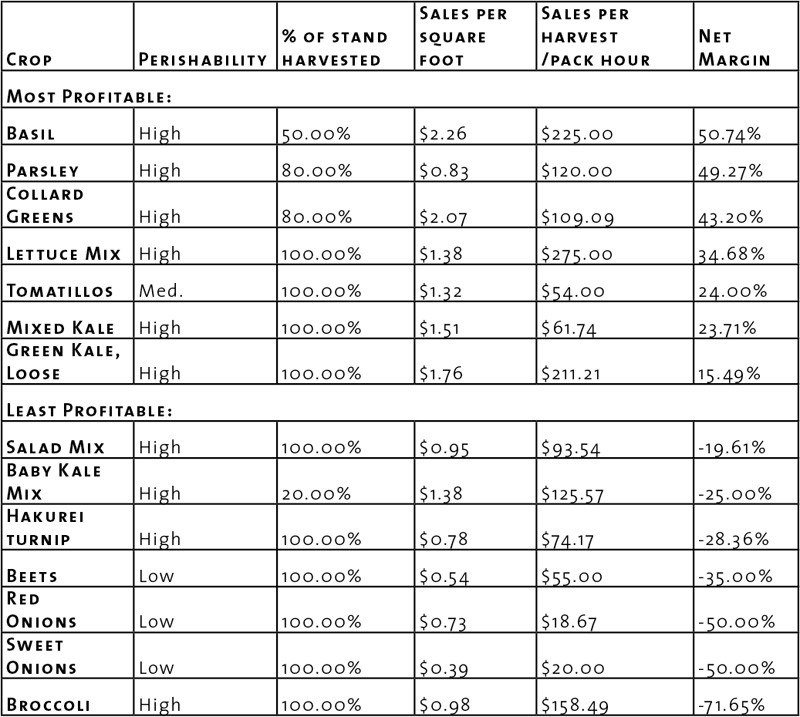

Those of you who read my last article in the May 2018 Growing for Market remember that the method we use to evaluate the potential profitability of our crops is to calculate the “unit cost” for each crop - that is, the minimum price we would need to receive in order to pay all of our expenses and ourselves. Calculating unit cost also provides us with the ability to compare the relative profitability of each crop by comparing each crop’s net margin (Net margin = (Price received - unit cost) / price received).

Those of you who read my last article in the May 2018 Growing for Market remember that the method we use to evaluate the potential profitability of our crops is to calculate the “unit cost” for each crop - that is, the minimum price we would need to receive in order to pay all of our expenses and ourselves. Calculating unit cost also provides us with the ability to compare the relative profitability of each crop by comparing each crop’s net margin (Net margin = (Price received - unit cost) / price received).