By Spencer Nietmann

Like it or not, it is hard to exaggerate the importance of money in our farming lives. Most of us chose this profession for reasons unrelated to income, but money is the ultimate trump card when it comes to our farms’ viability. Put simply, if a farm spends more money than it earns for more than a short amount of time, no amount of planting plans, fertility regimens, or even tenacious hard work will keep it afloat.

It follows, then, that we as farmers should talk about money. The more we can use each other as financial sounding boards, the more profitable, comfortable, and ultimately sustainable our farms will become. The least sustainable thing a farm can do, after all, is go out of business.

Unfortunately, money is a rather taboo topic among farmers. We readily share information regarding all other aspects of our work, but those farms that are willing to make their balance sheets public are few and far between.

So here is my call to action: let’s be more open with each other about how much we make, how much we spend and how many hours we work, because whether we are proud of those numbers or ashamed, discussing them with fellow farmers will make all of us better at what we do. Money is emphatically NOT the reason I farm, but I recognize its importance nonetheless. So here goes, I’ll step off my soapbox and get started.

Context

To give the following financial discussion some context, I’ll first provide a brief description of our farm in its current state. 2019 was our third full year of operation. We grow on ¾ of an acre, with about a third of that space (12,000 square feet) under heated and unheated polyfilm tunnels. We are certified organic and everything we sell is soil-grown.

The farm is in rural north Idaho, and we sell direct-to-consumer within a 30-mile radius of the farm and to independent grocery stores and restaurants within 100-miles. We operate year-round and sell produce 52 weeks a year. My wife and I derive 100% of our income from the farm.

Revenue

In 2019, our gross sales totaled $130,500. This is up from $42,000 in 2017 and $92,000 in 2018. We currently have three main sales outlets. The first is what we call wholesale direct: sales to regional grocery stores and restaurants. This outlet made up $70,000, or 54%, of our 2019 revenue. Within the wholesale category, $30,000 was clam-shelled salad greens, $26,000 was microgreens, $12,000 was tomatoes, and $2,000 was small amounts of other vegetables.

Our second sales outlet is a 22-week summer CSA, serving 64 members, which accounted for $39,000 or 30% of our 2019 sales.

The final outlet is our winter retail sales, which run mid-October through mid-May, and allow anyone to buy any amount through our weekly online marketplace. This is similar to a free-choice CSA, but without the memberships. It accounted for 16% or $21,000 of our total sales in 2019.

Expenses

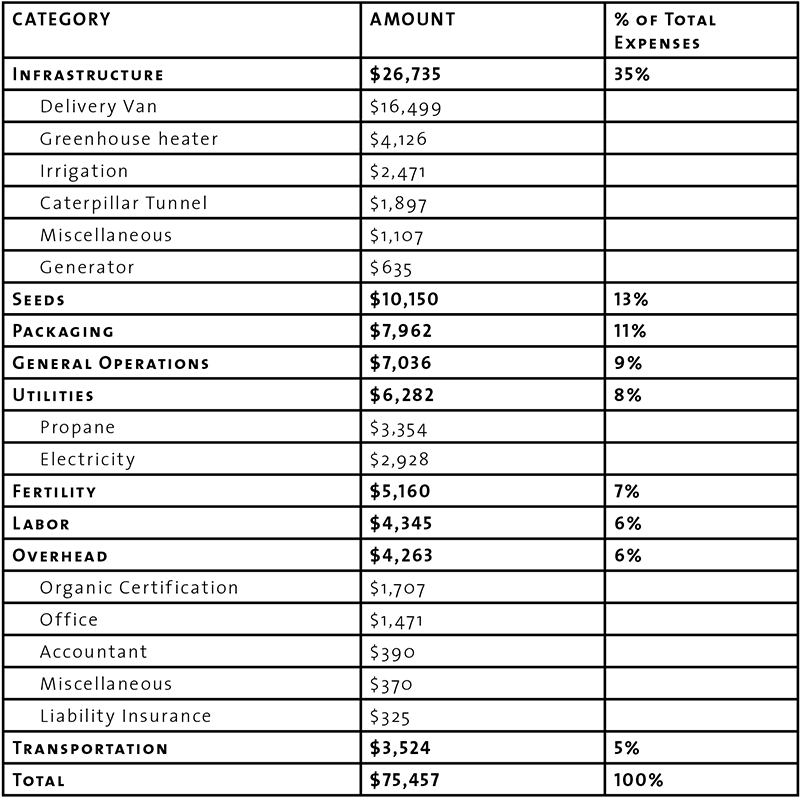

I must start this section by saying that we are not trained bookkeepers. We have divided our expenses into categories that make sense to us and are relevant to the way we decided to track expenses. We broke our expenses into nine categories: overhead, infrastructure, labor, transportation, packaging, seeds, fertility, utilities, and general operations.

There are likely much clearer models to follow if you are just beginning to consciously track categorized expenses. I have chosen to include our expenses in table form (see Table 1), because many of the expense items do not need discussion. Those that do are detailed below.

Overhead includes recurring costs that are independent of our level of production. Things like organic certification, liability insurance, and office supplies fall into this category. Infrastructure includes one-time purchases like equipment or high tunnels. The labor category is discussed in detail below. Transportation includes fuel, maintenance, licensing, and insurance for our delivery van. Packaging, seeds, soil fertility, and utilities should need no explanation. The general operations category includes recurring expenses that relate directly to production and yet don’t fall into our other categories. Things like trellis string, paper chain pots, beneficial insects, and potting soil fall into this category. All told, our 2019 expenses totaled $75,500, or 57% of our revenue.

Labor

We have a delivery driver who works two days per week in the summer and one day per week in the winter. He worked 317 hours in 2019, and we pay him $12 per hour plus vegetables from the farm. The cost to us for having such an employee is $13.70 per hour of his time, which includes all federal and state withholdings (Medicaid, Social Security, workers compensation insurance) and our bookkeeper’s fee.

We feel it is in all parties’ interests to follow all regulations with our employee like any other business would. As we hire additional labor, the same principals will hold: we plan to have only fairly compensated, legal employees on our farm, to whom we offer the greatest benefits we are able such as a living wage, maternity/paternity leave, paid time off, produce from the farm, and a stipend for work clothing.

Beyond our delivery driver, all of the farm labor currently comes from my wife and me. We keep daily records of our labor, since we want to see our income per hour increase each year. We both worked 2,080 hours in 2019, which coincidentally averages to 40 hours per week for the year. We rarely work a normal 40-hour week, though. In the summer months we each work about 60 hours per week, in the spring and fall we each work about 40, and in the winter months we work 20 hours per week.

Profit

Whether our farm is profitable is a question of how we pay ourselves and how we value our labor. For the first three years of our farm, we have opted to not pay ourselves a wage, choosing instead to simply balance our personal expenses with our farm expenses.

In other words, farm revenue that is not spent on farm operations can be spent or saved personally. In 2019, with our $130,500 in sales and $75,500 in expenses, my wife and I paid ourselves $55,000. With our combined 4160 labor hours, that means we each made $13.22 per hour of farm work.

You could say that the farm is profitable if we value labor below that number, and is not profitable if we value labor above that number. Put another way, the farm would be profitable in a traditional sense if we paid ourselves $13 per hour or less. However, if we had chosen to take on debt and make payments on some of our larger infrastructure purchases, our hourly wage in 2019 could have been significantly higher.

If instead of paying almost $27,000 in cash for our infrastructure projects we had paid $12,000 in loan re-payments for the same infrastructure, for example, our hourly wage would jump to over $16 per hour. We opted to spend less money overall by not carrying debt. But by using loans we could have spent less money in 2019, and therefore had a higher wage.

In 2020, we plan to actually pay ourselves a steady, on-the-books wage, and to bring on another crewmember and pay them a wage too. By changing the business structure from a sole proprietorship to an LLC and filing taxes as an S-Corp, paying both our workers and ourselves a wage or salary will help us minimize our income tax liabilities.

It will also keep us honest in our quest for farm profitability. Our goal is to be profitable with all labor valued at $15 per hour. This seems like a sustainable income for both us as the owners and for our employees, especially if there is money left over for farm improvements and/or personal savings after those wages are paid.

Is it enough?

Every farmer inhabits a different financial landscape, and peanuts to some would feel like overflowing bounty to others, and vice versa. For us, the $55,000 we were able to pay ourselves in 2019 is a comfortable amount. We are fortunate that we farm family land and have grown the business without any debt, so our income isn’t crippled by sizable monthly payments. Even our house is paid for.

We have simple tastes, so our income allows us to buy the things we need or want without considering how we might make ends meet. It is also enough to put between $10,000 and $15,000 per year into retirement investments, an expense that we have planned for from the start of the farm, and one we feel is critical to our long-term wellbeing.

Finally, since both my wife and I make $27,500 per year currently, we each qualify for a $300 monthly credit toward our health insurance through the federal government’s Advance Premium Tax Credit. Our contentedness with our current income would be lower if we were paying for health insurance out of pocket.

I should note that our contentment with our income did not happen by chance. We made conscious and calculated decisions about which crops to grow and how to sell them before we even plowed up our farm’s first field, and we have had concrete lifestyle goals in mind from the outset.

Specifically, our goals are to work less than 45 hours per week in the summer months, and to have enough income to save for retirement while pursuing our non-farming hobbies and interests. In a word, we planned to farm as a job, not as a lifestyle. We wanted to grow the farm’s revenue quickly to a point where we could be comfortable in our income and simultaneously afford to pay a crewmember a living salary. These two things would give us good balance between work and leisure.

As of this writing we have grown our income to a comfortable point. The last piece of the puzzle moving forward is to maintain that income while easing our workload. There are a handful of changes we plan to make in the coming year to help us achieve this goal, including hiring a year-round, salaried crew member, increasing per-plant production of tomatoes and bell peppers, and adding 5,000 square feet of greenhouse space to bolster our winter production.

It is important to note we feel strongly that the farm must generate enough income to pay an employee fairly, without sacrificing our own income. This will ensure that we can attract and retain reliable help, which in turn buys us some degree of independence from the farm. Farming is a dream job for me, but I want to do as little of it as possible.

For now, we are satisfied with our financial situation. We are always looking for ways to produce more food with fewer costs, though, and we welcome the chance to discuss financials and efficiencies with our farming peers. With that in mind, I hope this article inspires others to lay their balance sheets bare, uncomfortable though it may be, so that we can all learn and grow.

After farming in Maine for many years, Katherine Creswell and Spencer Nietmann started Moose Meadow Farm in Clark Fork, Idaho in 2016. Follow them on Facebook and Instagram to see the twists and turns their farm takes!

I’ve been teaching business skills and financial management to farmers for over ten years. When I started out, I was fresh out of business school and teaching college accounting. I was very academic in my approach.

I’ve been teaching business skills and financial management to farmers for over ten years. When I started out, I was fresh out of business school and teaching college accounting. I was very academic in my approach.

Here's a system to track all those details

Here's a system to track all those details

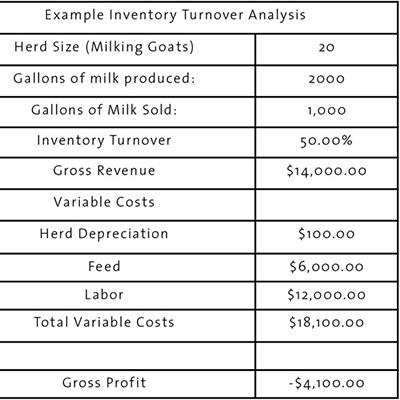

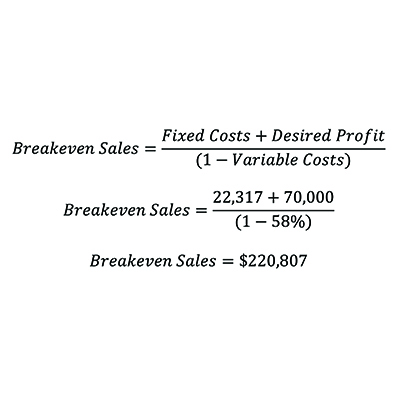

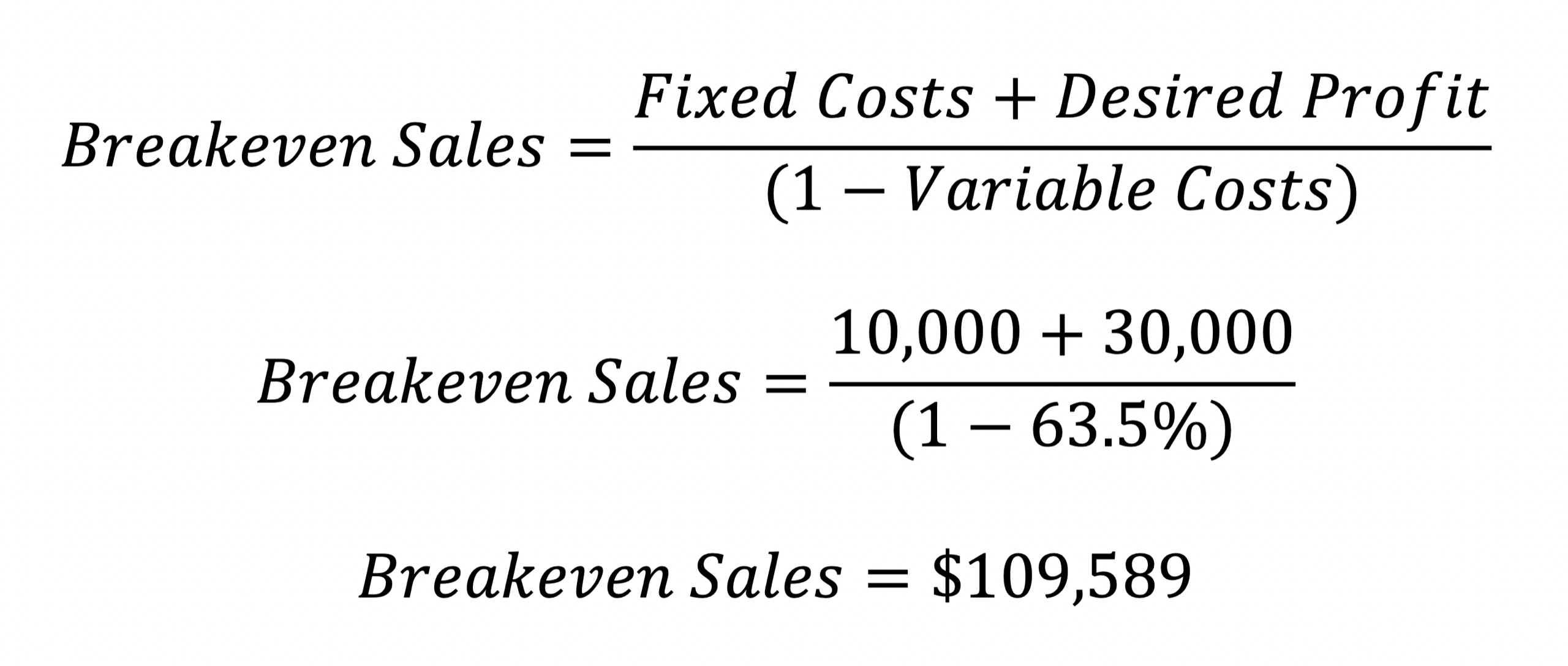

At the risk of taking the romance and wonder out of our profession, I think that farming can be boiled down to two important tasks: figuring out how to make money, and figuring out how to spend money. It might appear oversimplified, but when farmers decide which crops to grow, where to sell them, what techniques to use in growing them, how and when to harvest, and so on through the production cycle, we are just deciding how to make money and how to spend money; or, in a word, how to manage cash flow.

At the risk of taking the romance and wonder out of our profession, I think that farming can be boiled down to two important tasks: figuring out how to make money, and figuring out how to spend money. It might appear oversimplified, but when farmers decide which crops to grow, where to sell them, what techniques to use in growing them, how and when to harvest, and so on through the production cycle, we are just deciding how to make money and how to spend money; or, in a word, how to manage cash flow.

The pool of flower farmers is growing quickly it seems, leading to some changes in the industry. Most importantly, flower seeds, bulbs, and tubers are selling out fast, are in limited supply, or are not available altogether. Be sure to get your orders in on time, which is basically as soon as the season for that item is over.

The pool of flower farmers is growing quickly it seems, leading to some changes in the industry. Most importantly, flower seeds, bulbs, and tubers are selling out fast, are in limited supply, or are not available altogether. Be sure to get your orders in on time, which is basically as soon as the season for that item is over.